2. 土壤与农业可持续发展国家重点实验室(中国科学院南京土壤研究所),南京 210008

微生物是土壤中最活跃的组成,在土壤C、N、S、P等养分循环中均起着重要作用[1]。硝化过程是全球N循环的关键环节之一,是指在好氧条件下铵态氮被氧化为硝态氮的过程,它是由微生物所驱动的,分别由两类化能自养微生物参与完成:首先是氨氧化微生物(Ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms,AOM)将氨氧化为亚硝态氮,再由亚硝酸氧化细菌(NOB)将亚硝态氧化为硝态氮,其中能将氨氧化为亚硝态氮的氨氧化微生物包括氨氧化细菌(AOB)和氨氧化古菌(AOA)[2-4]。但新发现的全程氨氧化细菌(Comammox)却在逐渐改变人们对硝化作用的传统认知,它能够将铵态氮直接氧化为硝态氮[5-8]。

早期基于细胞的形状和内细胞膜的排列方式将氨氧化细菌分为不同的属[9]。根据伯杰氏分类手册,氨氧化细菌分为亚硝化单胞菌属(Nitrosomonas)、亚硝化球菌属(Nitrosococcus)、亚硝化螺菌属(Nitrosospira)、亚硝化叶菌属(Nitrosolobus)和亚硝化弧菌属(Nitrosovibria)[9-10]。近年来基于16S rRNA基因序列同源性的比较为研究氨氧化细菌系统发育提供了新的工具,氨氧化细菌在系统发育角度由2类不同的菌属组成,分别为变形菌门(Proteobacteria)的β和γ亚纲。已发现的土壤和淡水中的氨氧化细菌均属于这两个类群。其中β亚纲的氨氧化细菌分为亚硝化单胞菌群(Nitrosomonas)和亚硝化螺菌群(Nitrosospira)两个分支。Head等[11-12]在这一研究基础上进一步分析,亚硝化螺菌属(Nitrosospira)、亚硝化叶菌属(Nitrosolobus)和亚硝化弧菌属(Nitrosovibria)的基因序列同源性很好,将三者划分为同一菌属Nitrosospira。γ亚纲单独形成一个分枝亚硝化球菌属(Nitrotscoccus)。因此现在基本按Nitrosococcus、Nitrosomonas和Nitrosospira分成三类。与氨氧化细菌不同,亚硝酸氧化细菌的系统发育则要复杂许多,根据细胞形态和16S rRNA基因序列的系统发育关系一般将NOB分为四个属[13]:硝化杆菌属(Nitrobacter)、硝化球菌属(Nitrococcus)、硝化刺菌属(Nitrospina)和属于硝化螺菌门(Nitrospirae)的硝化螺菌属(Nitrospira)。

紫色土是土壤学科中具有特殊地位的土壤之一,主要分布在中国的亚热带地区,以四川盆地为主,在我国农业生产中占有十分重要的地位。按照pH和碳酸盐含量分为酸性、中性和石灰性紫色土[14]。土壤pH是影响土壤硝化作用的因素之一,不仅会对土壤硝化作用的进程产生影响,而且还会对硝化微生物的数量和群落结构产生影响[15]。

本实验选取采自重庆永川的酸性紫色土(pH=5.3)和中性紫色土(pH=7.2)以及四川盐亭的石灰性紫色土(pH=8.5),采用稳定性同位素标记技术进行培养实验。通过Miseq测序揭示三种不同的紫色土中总微生物和硝化微生物群落的分布情况,为进一步研究紫色土中的硝化作用提供理论基础。

1 材料与方法 1.1 供试土壤酸性紫色土采自重庆永川(29°11'N,105°47'E),海拔582 m;中性紫色土采自重庆永川(29°23'N,105°59'E),海拔387 m,亚热带气候,全年平均气温19.7℃,平均降水量1400 mm;石灰性紫色土采自四川盐亭中国科学院成都山地所(N31°16',E105°28'),海拔400~600 m,亚热带气候,全年平均气温17.3℃,平均降水量826 mm。

|

|

表 1 三种紫色土的基本理化性质 Table 1 Basic physico-chemical properties of the three types of purple soils tested |

13CO2标记处理,即13C-尿素处理。每周每个培养瓶内加入178.6 μl的0.1 mol L-1的尿素溶液,使得每克干土中N的浓度达到100 μg(将尿素溶液逐滴加入土壤,尽量均匀地加在培养瓶底部所有土壤表面)。加完尿素后密封培养瓶,随后注入6.0 ml的13CO2,进一步培养。

12CO2对照处理,即12C-尿素处理。每周每个培养瓶中加入178.6 μl的0.1 mol L-1的尿素溶液,密封培养瓶,随后注入6.0 ml的12CO2,进一步培养。

13CO2+C2H2对照处理,即13C-尿素加1 000 Pa C2H2抑制处理。每周每个培养瓶内加入178.6 μl的0.1 mol L-1的尿素溶液,密封培养瓶,随后注入6.0 ml的13CO2以及1.2 ml的C2H2,进一步培养。

培养8周后样品采集,利用试剂盒提取土壤基因组总DNA,采用FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil(MP Biomedicals公司)试剂盒进行提取。

1.3 总微生物量(16S rRNA)-Miseq测序目的基因的扩增及纯化:(1)将提取的DNA样品利用通用引物(515F/907R)扩增。扩增条件:94℃,5 min;32×(94℃,30s;54℃,30 s;72℃,45 s);72 ℃,10 min;在4℃下保存,进行普通PCR扩增,得到PCR产物。515F/907R引物对样品微生物DNA的16S rRNA的V4区进行扩增。(2)获得土壤DNA水平的16SrRNA基因扩增产物后,将PCR产物用2%的琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测,切胶,利用Agarose Gel DNA Fragment Recovery Kit Ver. 2.0试剂盒(Takara公司)纯化,纯化产物溶解于25 μl无菌超纯去离子水。(3)纯化后的PCR产物通过1.2%琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测纯化效果,利用微量紫外分光光度计(NanoDrop ND-1000 UV-Vis)测定扩增产物的浓度。

Miseq文库的构建及测序:将不同样品的PCR扩增产物等摩尔数混合后,进行Miseq文库构建,进行Miseq序列分析。测序在中国科学院南京土壤研究所分析测试中心完成。

1.4 数据处理Miseq测序得到的结果采用RDP online analysis、Mothur等软件及方法分析。采用Excel 2010和SPSS 13对数据进行统计分析。利用Origin 8.5软件作图。

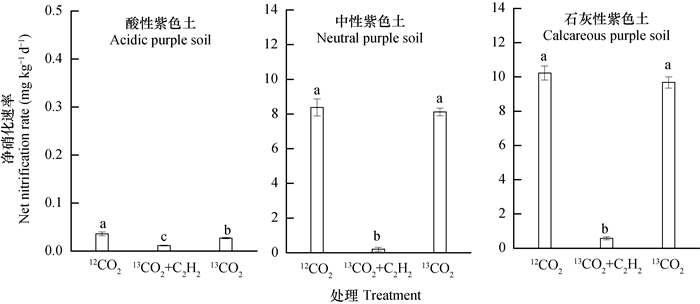

2 结果 2.1 三种紫色土各处理的净硝化速率经过56 d的培养后,三种紫色土各处理的净硝化速率如图 1所示。酸性紫色土12CO2、13CO2+C2H2和13CO2处理的净硝化速率依次为:0.036、0.012、0.027 mg kg-1d-1,酸性紫色土未发生明显的硝化作用。中性紫色土的净硝化速率为:8.373、0.199、8.123 mg kg-1d-1,石灰性紫色土的净硝化速率为:10.233、0.573、9.676 mg kg-1d-1。在pH较高的中性和石灰性土壤中发生了明显的硝化作用。

|

图 1 3种不同pH紫色土的硝化作用 Fig. 1 Net nitrification rates in the three purple soils with differentpH 注:误差线表示标准差。不同字母表示p<0.05水平上差异显著 Note:Error bars represent standard deviations, n=3.Different letters mean significant differences at 0.05 level |

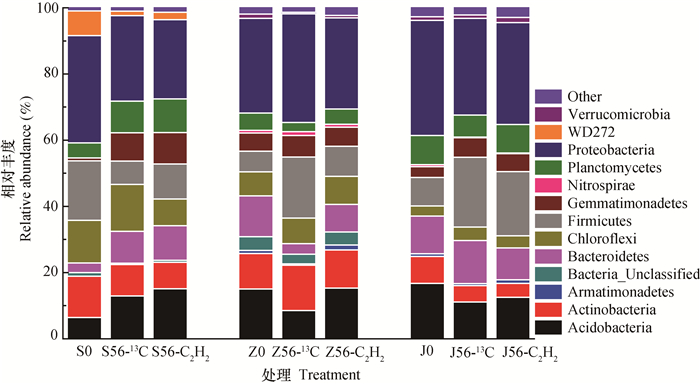

三种紫色土各处理样品中微生物类群占土壤微生物总量的比例如图 2所示。三种紫色土中均检测到了变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、酸杆菌门(Acidobacteria)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria)、拟杆菌(Bacteroidetes)、浮霉菌门(Planctomycetes)和芽单胞菌门(Gemmatimonadetes)等。但其相对丰度在三种紫色土各处理样品中存在较大差异。丰度低于1%的微生物合并为Other。

|

图 2 三种紫色土各处理样品土壤微生物门水平分类比例 Fig. 2 Proportions of soil microbes by phylum in the three purple soils with different pH |

酸性紫色土培养初期(S0)Proteobacteria占微生物总量的32.5%。加入尿素经过56 d培养13C处理(S56-13C)和乙炔抑制处理(S56-C2H2)后Proteobacteria占微生物总量的比例分别为25.8%和23.9%,均有一定程度的下降。中性紫色土中加入尿素经过56d培养13C处理(Z56-13C)和乙炔抑制处理(Z56-C2H2)后Proteobacteria占微生物总量的32.8%和27.5%,相比于培养初期的28.6%,乙炔处理抑制了Proteobacteria的增长。石灰性紫色土中加入尿素经过56d培养13C处理(J56-13C)和乙炔抑制处理(J56-C2H2)后Proteobacteria占微生物总量的比例分别为29.2%和30.7%。中性紫色土和石灰性紫色土中硝化螺旋菌门(Nitrospirae)的比例大于酸性紫色土。

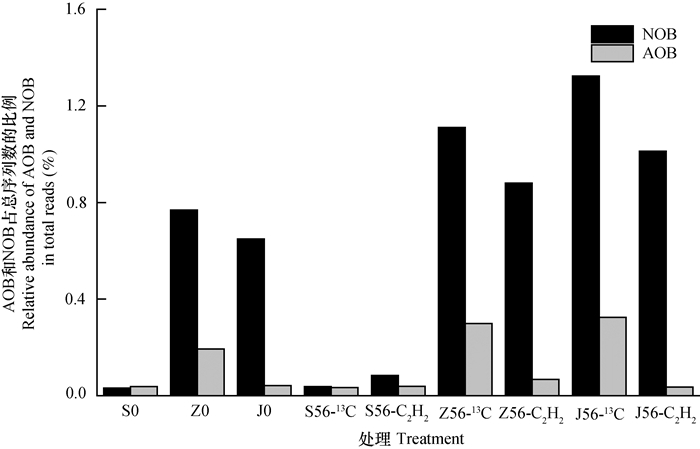

2.3 三种紫色土各处理硝化细菌群落组成在所有序列中挑出属于AOB和NOB的序列,三种紫色土各处理AOB和NOB占总序列的比例如图 3。

|

图 3 三种紫色土各处理AOB和NOB占总微生物的百分比 Fig. 3 Relative abundance of AOB and NOB in the three purple soils with different pH |

酸性、中性和石灰性紫色土培养初期(S0、Z0和J0)AOB分别占总序列的0.032%、0.193%和0.042%,NOB分别占总序列的0.038%、0.769%和0.649%。加入尿素经过56d培养13C处理(S56-13C、Z56-13C和J56-13C)AOB分别占总序列的0.034%、0.298%和0.324%,NOB分别占0.038%、1.111%和1.324%。加入尿素经过56d培养乙炔抑制处理(S56-C2H2、Z56-C2H2和J56-C2H2)AOB分别占总序列的0.038%、0.067%和0.036%,NOB分别占0.084%、0.88%和1.012%。酸性紫色土加入尿素经过56 d培养13C处理和乙炔抑制处理的NOB和AOB比例均无明显变化。中性紫色土经过培养NOB比例分别增长了1.4倍和1.1倍;AOB比例分别增长了1.5倍和0.34倍。石灰性紫色土经过培养NOB比例分别增长了2.1倍和1.5倍;AOB分别增长了7倍和0.86倍。NOB/AOB的值在三种紫色土各处理中最高可达到13。

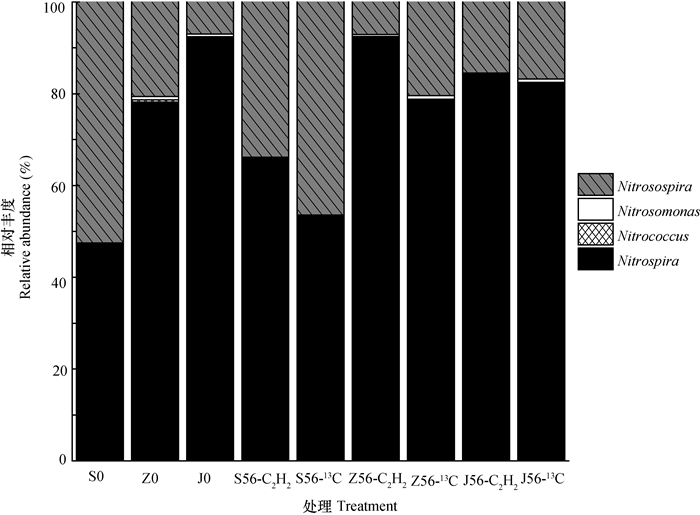

三种紫色土各处理下AOB和NOB序列在属水平百分比如图 4,其中硝化螺菌属(Nitrospira)和硝化球菌属(Nitrococcus)属于NOB,亚硝化单胞菌属(Nitrosomonas)和亚硝化螺菌属(Nitrosospira)属于AOB。三种紫色土各处理AOB主要以Nitrosospira为主,NOB主要以Nitrospira为主。

|

图 4 三种紫色土各处理AOB和NOB在属水平所占的百分比 Fig. 4 Relative abundance of AOB and NOB at the level of genera in the three purple soilswith different pH |

酸性、中性和石灰性紫色土培养初期(S0、Z0和J0)AOB分别占52.5%、21.3%和7.6%,NOB分别占47.5%、78.7%和92.4%,酸性、中性和石灰性紫色土加入尿素培养56 d13C处理(S56-13C、Z56-13C和J56-13C)AOB分别占46.4%、21.1%和17.5%,NOB分别占53.6%、78.8%和82.5%。酸性、中性和石灰性紫色土加入尿素培养56d乙炔抑制处理(S56-C2H2、Z56-C2H2和J56-C2H2)AOB分别占33.8%、7.5%和15.5%,NOB分别占66.2%、92.5%和84.5%。经过56d培养13C处理后,酸性紫色土AOB所占比例下降幅度较大,中性紫色土有较小幅度的下降,石灰性紫色土所占比例增加。经过56d培养乙炔抑制处理后,酸性紫色土、中性紫色土AOB所占比例均有较大幅度下降,NOB所占比例变化情况相反。而石灰性紫色土AOB所占比例有较小幅度的增长,NOB所占比例有所下降。

3 讨论实验室模拟试验与田间试验结果均表明:硝化作用在一定的范围内随着pH的升高而增强[16-20]。本次试验的结果表明,pH8.5的石灰性紫色土和pH7.2的中性紫色土中发生了强烈的硝化作用,而pH5.3的酸性紫色土中硝化作用则较为微弱。随着pH的升高,紫色土中的硝化作用也有着明显的增强。

本研究中,在乙炔抑制处理下的紫色土中几乎未发生硝化作用,而未加乙炔的处理有明显的硝化作用,表明三种不同pH紫色土中的硝化作用类型均以自养硝化作用为主。乙炔是一种常用的自养硝化抑制剂,在很多情况下较低的乙炔浓度可以抑制土壤的自养硝化作用[21]。土壤中的自养硝化微生物利用硝化作用产生的能量同化CO2自养生长。

三种紫色土中均检测到了变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、酸杆菌门(Acidobacteria)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi)、放线菌(Actinobacteria)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)和芽单胞菌门(Gemmatimonadetes),但其占比在三种紫色土中存在着显著的差异。不同的土壤条件,例如pH,会影响微生物和硝化微生物的分布情况[22-23]。中性紫色土和石灰性紫色土各处理中硝化螺旋菌门(Nitrospirae)百分比大于酸性紫色土各理。

AOB隶属于Proteobacteria,在三种紫色土中均检验到了较高的占比。但酸性紫色土中的硝化作用远小于中性紫色土和石灰性紫色土,表明在酸性紫色土的硝化作用中AOB并不起主导作用[24-25]。加入尿素经过56 d培养13C处理后石灰性紫色土中AOB占总微生物的百分比的增长倍数远大于中性紫色土和石灰性紫色土,乙炔抑制处理后则均有不同程度的下降。

三种紫色土各处理AOB主要以Nitrosospira为主,NOB主要以Nitrospira为主,这表明在硝酸盐氧化过程中Nitrosospira的活性高于Nitrosomonas,Nitrospira的活性要高于Nitrococcus。Nitrosomonas在高浓度铵环境下存在,而Nitrosospira在自然环境中经常被发现,Nitrospira对亚硝酸盐的亲和力较高[26-28]。NOB的相对量要大于AOB。在测序结果中,门水平未找到氨氧化古菌,因此在文中并没有进行作图。经典的硝化作用过程由两个步骤完成:氨氧化细菌(AOB)和氨氧化古菌(AOA)先将氨氧化成亚硝酸盐,然后亚硝酸氧化细菌(NOB)将亚硝酸盐氧化成硝酸盐。氨氧化微生物(AOM)将铵氧化成亚硝酸盐产生6个电子,较亚硝酸氧化细菌(NOB)将亚硝酸氧化成硝酸盐产生的电子量多3倍,由于氨氧化微生物(AOM)代谢时氨单加氧酶活化铵需要2个电子,因此氨氧化微生物(AOM)转化每单位氮真正释放的能量仅较亚硝酸盐氧化细菌(NOB)释放的多2倍。这意味着理论上环境中AOM /NOB的数量比是2[29-32]。但本次试验中检验到的紫色土中的NOB的相对量要大于AOB。最近有研究表明,Nitrospira属中的一类能够进行全程硝化作用[5-6],即能将氨直接氧化为硝酸盐。本次试验中NOB/AOB的值在三种紫色土各处理中最高可达到13,这意味着全程氨氧化细菌(Comammox)可能在紫色土硝化中占据重要贡献[5, 33]。从热力学的角度来看,在细菌群落中AOB的数量应该较NOB要多,但很多试验得出的结论却与之相反[33-34]。相比于分步的硝化作用,全程硝化作用会产生出更高的能量,进行全程硝化作用的硝化微生物应该更适宜生长。许多已经发表的宏基因组数据表明能进行全程硝化作用的Nitrospira广泛分布于土壤、淡水生态系统、污水处理厂和饮用水处理系统中[5-8]。因此我们需要有更多的工作来评估各种硝化微生物在土壤硝化作用中的贡献。通过对此次试验中13C标记结果的后续探究,我们也可以进一步了解各种硝化微生物到底是否在土壤的硝化过程中发挥了作用,如果被标记,则证明此类硝化微生物在土壤进行的自养硝化过程中起了作用。

4 结论pH较高的中性紫色土(pH=7.2)和石灰性紫色土(pH=8.5)中发生了强烈的硝化作用,而酸性紫色土(pH=5.3)中未进行明显的硝化作用,并且硝化作用类型均以自养硝化为主。三种紫色土中均存在着变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、酸杆菌门(Acidobacteria)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)和芽单胞菌门(Gemmatimonadetes),其中Proteobacteria在三种紫色土中均大约占有20%的比例。中性紫色土和石灰性紫色土各处理中硝化螺旋菌门(Nitrospirae)的百分比大于酸性紫色土各处理。三种紫色土中AOB主要以亚硝化螺菌属(Nitrosospira)为主,NOB主要以硝化螺菌属(Nitrospira)为主,且NOB的相对量大于AOB。

| [1] |

宋长青, 吴金水, 陆雅海, 等. 中国土壤微生物学研究10年回顾. 地球科学进展, 2013, 28(10): 1087-1105. Song C Q, Wu J S, Lu Y H, et al. Advances of soil microbiology in the last decade in China (In Chinese). Advances in Earth Science, 2013, 28(10): 1087-1105. DOI:10.11867/j.issn.1001-8166.2013.10.1087 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Prosser J I. Autotrophic nitrification in bacteria . Advances in Microbial Physiology, 1989, 30(1): 125-181.

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Leininger S, Urich T, Schloter M, et al. Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils . Nature, 2006, 442(7104): 806-809. DOI:10.1038/nature04983

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Brochierarmanet C, Boussau B, Gribaldo S, et al. Mesophilic crenarchaeota:Proposal for a third archaeal phylum, the Thaumarchaeota . Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2008, 6(3): 245-252. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro1852

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

van Kessel M A H J, Speth D R, Albertsen M, et al. Complete nitrification by a single microorganism . Nature, 2015, 528(7583): 555-559. DOI:10.1038/nature16459

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Daims H, Lebedeva E V, Pjevac P, et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria . Nature, 2015, 528(7583): 504-509. DOI:10.1038/nature16461

(  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Pinto A J, Marcus D N, Ijaz U Z, et al. Metagenomic evidence for the presence of comammox Nitrospira-like bacteria in a drinking water system . mSphere, 2016, 1(1). DOI:10.1128/mSphere.00054-15

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Palomo A, Jane F S, Gülay A, et al. Metagenomic analysis of rapid gravity sand filter microbial communities suggests novel physiology of Nitrospira spp . The ISME Journal, 2016, 10(11): 2569-2581. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2016.63

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Koops H P, Purkhold U, Pommerening-Röser A, et al. The lithoautotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. New York: Springer, 2006: 141-147

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Balows A. The Prokaryotes: A handbook on the biology of bacteria: ecophysiology, isolation, identification, applications. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1992

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Head I M, Hiorns W D, Embley T M, et al. The phylogeny of autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria as determined by analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences . Microbiology, 1993, 139(6): 1147-1153.

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Utåker J B, Nes I F. A qualitative evaluation of the published oligonucleotides specific for the 16S rRNA gene sequences of the ammonia-oxidizing bacteria . Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 1998, 21(1): 72-88. DOI:10.1016/S0723-2020(98)80010-6

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Teske A, Alm E, Regan J M, et al. Evolutionary relationships among ammonia-and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria . Journal of Bacteriology, 1994, 176(21): 6623-6630. DOI:10.1128/jb.176.21.6623-6630.1994

(  0) 0) |

| [14] |

李仲明, 唐时嘉, 张先婉. 中国紫色土. 北京: 科学出版社, 1991. Li Z M, Tang S J, Zhang X W. Purple soils in China (In Chinese). Beijing: Science Press, 1991. (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Jiang X J, Hou X Y, Zhou X, et al. pH regulates key players of nitrification in paddy soils . Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2015, 81: 9-16.

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Bernie J Z, Thomas A F, Claudia G, et al. Effect of soil acidification on nitrification in soil . Canadian Journal of Soil Science, 2015, 95(4): 359-363. DOI:10.4141/cjss-2015-040

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Krave A S, van Straalen N M, van Verseveld H W. Potential nitrification and factors influencing nitrification in pine forest and agricultural soils in Central Java, Indonesia . Pedobiologia-International Journal of Soil Biology, 2002, 46(6): 573-594.

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Cheng Y, Wang J, Mary B, et al. Soil pH has contrasting effects on gross and net nitrogen mineralizations in adjacent forest and grassland soils in central Alberta, Canada . Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2013, 57(3): 848-857.

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Dai Z, Wang Y, Muhammad N, et al. The effects and mechanisms of soil acidity changes, following incorporation of biochars in three soils differing ininitial pH . Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2014, 78(5): 1606-1614. DOI:10.2136/sssaj2013.08.0340

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

蔡祖聪, 赵维. 土地利用方式对湿润亚热带土壤硝化作用的影响. 土壤学报, 2009, 46(5): 795-801. Cai Z C, Zhao W. Effects of land use types on nitrification in humid subtropical soils of China (In Chinese). Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2009, 46(5): 795-801. DOI:10.11766/trxb200810280506 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Freney J R, Randall P J, Smith J W B, et al. Slow release sources of acetylene to inhibit nitrification in soil . Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 2000, 56(3): 241-251. DOI:10.1023/A:1009866902673

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Hu B L, Liu S, Wang W, et al. pH-dominated niche segregation of ammonia-oxidising microorganisms in Chinese agricultural soils . FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2014, 90(1): 290-299. DOI:10.1111/fem.2014.90.issue-1

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Mosier A C, Francis C A. Relative abundance and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in the San Francisco Bay estuary . Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 10(11): 3002-3016.

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Zhang L M, Hu H W, Shen J P, et al. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea have more important role than ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in ammonia oxidation of strongly acidic soils . The ISME Journal Multidisciplinary Journal of Microbial Ecology, 2012, 6(5): 1032-1045.

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Qin H L, Yuan H Z, Zhang H, et al. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea are more important than ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in nitrification and NO3--N loss in acidic soil of sloped land . Biology & Fertility of Soils, 2013, 49(6): 767-776.

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Kowalchuk G A, Stephen J R. Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria:A model for molecular microbial ecology . Annual Reviews of Microbiology, 2001, 55(1): 485-529. DOI:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.485

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Koops H P, Pommerening-Röser A. Distribution and ecophysiology of the nitrifying bacteria emphasizing cultured species . FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2001, 37(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1111/fem.2001.37.issue-1

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Taylor A E, Zeglin L H, Dooley S, et al. Evidence for different contributions of archaea and bacteria to the ammonia-oxidizing potential of diverse Oregon soils . Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 76(23): 7691-7698.

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Aleem M I. Generation of reducing power in chemosynthesis. Ⅱ. Energy-linked reduction of pyridine nucleotides in the chemoautotroph, Nitrosomonas europaea . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Enzymology & Biological Oxidation, 1966, 113(2): 216-224.

(  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Ferguson S J. Is a proton-pumping cytochrome oxidase essential for energy conservation in Nitrobacter? . FEBS Letters, 1982, 146(2): 239-243. DOI:10.1016/0014-5793(82)80927-7

(  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Hagopian D S, Riley J G. A closer look at the bacteriology of nitrification . Aquacultural Engineering, 1998, 18(4): 223-244. DOI:10.1016/S0144-8609(98)00032-6

(  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Hooper A B, Vannelli T, Bergmann D J, et al. Enzymology of the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite by bacteria . Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 1997, 71(1/2): 59-67. DOI:10.1023/A:1000133919203

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Lapara T M, Hope W K, Strait J M, et al. The bacterial communities of full-scale biologically active, granular activated carbon filters are stable and diverse and potentially contain novel ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms . Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 2015, 81(19): 6864-6872.

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

White C P, Debry R W, Lytle D A. Microbial survey of a full-scale, biologically active filter for treatment of drinking water . Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78(17): 6390-6394.

(  0) 0) |

2. State Key Laboratory of Soil and Sustainable Agriculture, Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China

2018, Vol. 55

2018, Vol. 55