2. 土壤与农业可持续发展国家重点实验室(中国科学院南京土壤研究所),南京 210008

根际是土壤中植物根系受到微生物特殊影响的重要区域,该区域从主根表面延伸几毫米,是植物-土壤-微生物相互联系的重要场所[1-2]。根际环境中,细菌与真菌密切联系,细菌以真菌的菌丝为通道进入土壤基质。腐生真菌依靠分泌的胞外酶分解利用有机质,附着在其菌丝上的细菌也可从这个过程中获取养分,从而抑制真菌的生长。细菌还可以与真菌合作,通过降解抑制真菌生长的有毒化合物或多糖,或通过固氮为真菌降解木质纤维素提供氮进而加快有机质的分解速率[3]。细菌和真菌的相互作用在生态系统的养分循环过程中起着关键作用,对植物的健康生长有重要影响[4]。Toro等[5]研究植物利用低生物有效性磷源时发现,双重接种丛枝菌根真菌和具有溶磷能力的枯草芽孢杆菌可显著增加作物的生物量和氮、磷积累量,证明根际促生细菌和菌根真菌之间的相互作用促进了营养元素的持续供应。根瘤菌和菌根真菌的互作可显著缓解半寄生植物对宿主的寄生危害[6],此外,生活在根际环境中的木霉、芽孢杆菌等可以通过与真菌病原体产生拮抗作用,减少病原微生物的传播,降低植物病害水平[7-8]。生态网络分析法(Ecological network analysis)可以将微生物群落的相互作用关系可视化,并揭示物种在微生境中的共现关系及主要影响因素[9],为解释复杂的微生物群落结构提供了一种新的方式。利用网络分析法可以揭示土壤重要元素生物地球化学耦合过程中微生物的互作机制,是预测和改善土壤生态系统服务功能的重要步骤[3]。已有报道利用网络分析法探讨土壤中细菌-真菌的相互作用关系,例如,Purahong等[10]使用网络分析法研究了凋落物分解过程中细菌和真菌群落的交互作用模式,证明凋落物分解的不同阶段是由细菌、真菌群落的变化和相互作用控制的。

生物质炭作为改良剂是目前改善土壤肥力和固碳减排的有效方法之一[11-13]。生物质炭以其特殊的结构和组成,可以改善土壤的许多特性,如促进团聚体的形成、增加阳离子交换量、增强养分吸收能力和持水能力以及减缓过量酸化等[14-16],在土壤改良和农作物增产等方面有良好的应用[17-18]。此外,生物质炭本身特有的芳香化表面、良好的多孔性结构以及极高的水肥吸附作用还可以为土壤微生物如细菌和真菌提供栖息地,增加微生物的生物量[19]。大量的研究证实,添加生物质炭可以改变微生物的群落结构和酶活性,这对于有机质积累、养分转化等土壤生态过程有着重要作用[20-23],从而间接影响植物的生长[24-26]。尽管生物质炭对土壤微生物的影响受到越来越多的关注,但是关于生物质炭对微生物群落生态网络的研究存在不足,尤其是对于生物质炭是如何影响根际土壤细菌-真菌群落相互作用的方面,仍缺乏相关研究。

水稻是世界主要粮食作物之一,种植广泛,研究水稻土具有重要的实用意义;黑麦草是优质的放牧用牧草,作为主要的绿肥有一定的研究基础。本研究选择水稻土和黑麦草作为试验材料,通过对16S rRNA(V4-V5区)和ITS2区的高通量测序,利用生态网络分析法构建施加生物质炭处理和未施加生物质炭的条件下黑麦草根际细菌-真菌群落互作网络,进一步揭示秸秆生物质炭对根际土壤细菌-真菌群落相互作用的影响及主要驱动因素,探讨生物质炭对根际土壤细菌-真菌群落互作模式的改变及主要机制。

1 材料与方法 1.1 供试材料供试土壤为黄棕壤,于2016年11月份采自中国江苏省常州市(119.75ºE,31.73ºN),采集水稻田0~10 cm土壤(非淹水条件下),风干后过2 cm筛并研磨粉碎备用。土壤的理化性质:比表面积28.73 m2·g-1,微孔面积4.57 m2·g-1,外表面积24.17 m2·g-1,微孔体积0.002 cm3·g-1;pH7.65,铵态氮含量1.24 mg·kg-1,硝态氮含量0.28 mg·kg-1,有效磷含量0.34 mg·kg-1。

供试黑麦草种子来自中国江苏省农业科学院牧草研究所。生物质炭样品由小麦秸秆在600 ℃缺氧条件下缓慢热解8 h而成。

1.2 研究方法试验为盆栽试验,设置添加生物质炭(生物质炭按2%的比例均匀添加到盆栽土壤中)和对照(未施加生物质炭)两组处理。每盆装土3 kg,种入30粒饱满的黑麦草种子,在种苗发芽后的第0、5、10、15、20、25、30、35、40天进行破坏性采样,3个重复,共计54盆。

采样时,将黑麦草从盆栽中取出,用抖落法将每盆土壤的根际土壤收集好并按要求保存,用于土壤理化性质和根际微生物的测定(若土样量无法达到测试要求,使用小型铁锹刮取根系周围 < 1 cm范围的土壤)。对应的黑麦草植株用于测定根系体表形态学参数。

土壤的pH、铵态氮、硝态氮和有效磷的测定参考文献[27]。土壤物理结构的测定:利用TriStar Ⅱ 3020全自动比表面积及孔隙度分析仪对各样品做氮气吸附、解吸试验,氮吸附在液氮温度(77 K)下操作。分析测试前,样品在150 ℃条件下真空(约10-2 Pa)脱气4 h,然后利用BET法[28]计算出样品的比表面积(SBET),利用t-plot模型[29]计算微孔比表面积(Smi)和孔体积(Vmi)。植物根系的测定:将洗净的根放入根盘内,根据植物根系测定方法[30],使用扫描仪(V700 Epson)扫描完整的根系图像存入计算机,采用WinRHIZO PRO 2007根系分析系统软件分析根系总长度、平均直径、平均长度、总表面积、总切面面积、平均表面积、平均切面面积等形态学参数。

1.3 DNA提取及高通量测序称取2 g土壤样品,加入液氮冷冻研磨,使用Power Soil DNA isolation kit提取土壤总DNA。提取后上机检测各样品DNA的质量和浓度,合格的样品在−80℃条件下保存。利用Illumina测序平台,对54个样本做细菌16S rRNA(V4-V5区)和真菌(ITS2区)高通量测序,以标准的细菌/真菌基因组DNA Mix作为阳性对照,根据选定的检测区域确定相对应的扩增引物,对各样本的检测区域做高保真PCR扩增。细菌16S rRNA(V4-V5区)扩增引物序列为:Primer F=Illumina adapter sequence 1 + GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGG,Primer R=Illumina adapter sequence 2 + CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT;真菌(ITS2区)扩增引物序列为:Primer F = Illumina adapter sequence 1+GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC,Primer R=Illumina adapter sequence 2+TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC。细菌16S rRNA(V4-V5区)区域扩增的PCR条件为:预变性步骤设置95 ℃、2 min;变性步骤设置94 ℃、20 s,退火步骤设置55 ℃、40 s,延伸步骤设置72 ℃、1 min,重复循环变性-退火-延伸三个步骤35次;末延伸步骤设置72 ℃、2 min。真菌(ITS2区)区域扩增的PCR条件为:预变性步骤设置94 ℃、2 min;变性步骤设置94 ℃、30 s,退火步骤设置55 ℃、30 s,延伸步骤设置72 ℃、1 min,重复循环变性-退火-延伸三个步骤25次;末延伸步骤设置72 ℃、10 min。利用带有Index序列的引物,通过高保真PCR将特定的标签序列导入文库末端。细菌样本添加特异性标签序列的PCR条件为:预变性步骤设置98 ℃、30 s;变性步骤设置98 ℃、10 s,退火步骤设置65 ℃、30 s,延伸步骤设置72 ℃、30 s,重复循环变性—退火—延伸三个步骤11次;末延伸步骤设置72℃、5 min。真菌样本添加特异性标签序列的PCR条件为:预变性步骤设置94 ℃、2 min;变性步骤设置94 ℃、30 s,退火步骤设置55 ℃、30 s,延伸步骤设置72 ℃、1 min,重复循环变性-退火-延伸三个步骤8次;末延伸步骤设置72 ℃、10 min。应用核酸纯化磁珠纯化扩增产物,得到样本的原始文库。利用Qubit荧光定量仪对文库精确定量,按相应比例(摩尔比)混合样本。通过Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer生物分析仪检测混样后的文库插入片段的大小,确认在120~200 bp之间无非特异性扩增,并准确定量测序文库浓度。采用Miseq系列测序仪2×250 bp的双端测序策略对文库做测序。

原始下机数据经过质量控制和过滤后,利用UPARSE软件对其做OTU(Operational Taxonomic Unit)聚类分析,分类依据参照RDP(RibosomalDatabase Project)数据库的RDP Release 11.5版本。细菌测序中每个样本获得的序列数范围为42 534~76 867 reads,为了尽量减少样本中读取计数变化的影响,我们基于样本序列最低数量(42 534 reads)对其做抽平化处理,按照97%的相似性对所有序列做OTU划分,各样品文库的覆盖率均达到98%以上。真菌测序中每个样本获得的序列数范围为44 941~98 438 reads,同样基于样本序列最低数量(44 941 reads)对其做抽平化处理,使各样品文库的覆盖率均达到98%以上,保证样本中绝大多数序列均可被测出,因此本次测序结果可以代表样本的真实情况。

1.4 数据分析根据Illumina测序得到的细菌和真菌的OTU数据,使用Cytoscape(3.5.0)软件中的CoNet插件构建微生物生态网络。分析步骤和网络参数的选择参照顾静馨[31]提供的操作方法,网络分析中,我们选择四种相关分析方法,即Pearson correlation,Spearman correlation,Bray-Curtis dissimilarity和Kullback-Leibler dissimilarity,并设置700的起始连接数。然后,采用Benjamini-Hochberg方法标准化处理相关系数,即校正原有假设检验得到的显著性P值(P-value),并最终采用校正后的P值,保留P < 0.05的相关OTU构建关联网络。利用NetworkAnalyzer工具,获得网络的特征路径长度、连接数、节点数、聚集系数、网络密度和平均连通度等网络拓扑参数。

根据中介中心性值(betweenness centrality scores)指标的最大值确定关键物种[32-33],中介中心性指的是一个节点担任其他两个节点之间最短路径的桥梁的次数。网络中任意两个节点的所有最短路径,如果这些最短路径中有很多条都经过了某个节点,那么就认为这个节点的中介中心性高。一个节点充当“中介”的次数越高,它的中介中心度就越大,说明节点在网络中承担的角色越重要。节点的中介中心值可由互作网络导出。

分子复合物检测(MCODE)是一种基于网络密度的网络模块识别算法,首先根据节点所在的、最高K-core值的密度为网络中的所有节点赋予一个权值,并选取具有最高权值的一个节点视作种子节点,依次向外扩增,将权值在阈值之上的周边节点依次纳入到模块中,直至没有节点可包含到该模块中为止。然后将选择剩余下来的节点中权值最高的视作种子节点做同样的操作。最后根据设定的K-core值将不满足条件的模块删除。使用Cytoscape(3.5.0)软件中的MCODE插件分析互作网络中高度互连节点的模块化结构和组,所有分析参数均采用标准值,即度数截止值设为2,节点得分截止值设为0.2,K-core值设为2,种子最大深度设为100。使用Mantel test分析方法评估土壤结构、环境因子以及植物根系等因子对根际土壤细菌-真菌群落相互作用的影响,Mantel test在微生物领域常被用于计算物种组成和环境因子之间的相关性,基于Pearson相关性分析以及置换检验计算统计学显著性P值,分析在R-studio v7.2中利用ecodist软件包实现。

2 结果 2.1 施加生物质炭对微生物互作网络结构的影响基于显著相关性对细菌和真菌的高通量测序数据构建互作网络(图 1),探究施加生物质炭处理下根际土壤细菌-真菌群落的共现模式,使用NetworkAnalyzer工具计算网络的拓扑参数(表 1)。可以看出,施加生物质炭对根际土壤细菌-真菌群落之间的共现模式产生重要影响,网络拓扑性质的分析表明,网络节点数、连接数、聚集系数、特征路径长度、网络密度和平均连通度等网络拓扑参数在对照组和生物质炭组之间显著不同(P < 0.05)。对照组中,根际土壤细菌-真菌群落的互作网络包含44个节点(其中细菌节点数为24,真菌节点数为20)、112条连线(其中28.6%为正连线,71.4%为负连线);生物质炭组中,根际土壤细菌-真菌群落的互作网络包含84个节点(其中细菌节点数为62,真菌节点数为22)、455条连线(其中51.6%为正连线,48.4%为负连线)。施加生物质炭后,网络的节点数增多,且主要表现为细菌节点数的增多,网络的连接数增多,正连接数占总连接数的比重增加,施加生物质炭显著增强了细菌-真菌互作网络的积极联系(P < 0.05)。与对照组相比,施加生物质炭处理条件下根际土壤细菌-真菌群落的互作网络表现出更高的网络密度、聚集系数和平均连通度。

|

注:每个节点表示一个真菌/细菌的OTU;红色连线表示节点间正相互作用,灰色连线表示节点间负相互作用;关键类群的节点放大标出。下同 Note: Each node represents an OTU of fungi/bacteria; the red connection represents the positive interaction between nodes, and the gray connection represents the negative interaction; nodes of key groups are amplified and marked out. The same below 图 1 两种处理下细菌-真菌共现模式的响应网络 Fig. 1 Network of the bacterial and fungal co-occurrence pattern relative to treatment |

|

|

表 1 两种处理下细菌-真菌互作网络的拓扑性质 Table 1 Topological parameters of the bacterial and fungal interaction network relative to treatment |

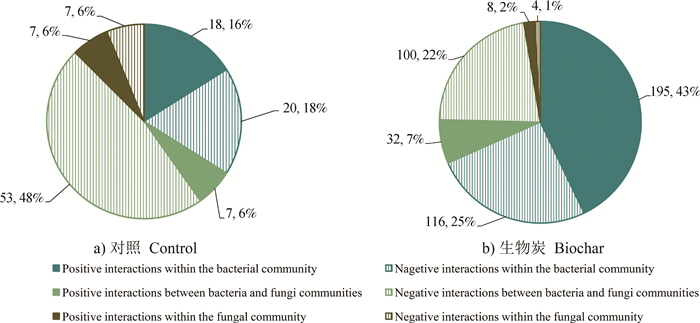

图 2展示了互作网络中群落之间连接数的分布情况。对照组中,细菌-真菌群落之间的相互作用(共60个相关中有7个正相关)居于主导地位,显著高于细菌群落内部(共38个相关中有18个正相关)以及真菌群落内部(共14个相关中有7个正相关)的相互作用。施加生物质炭处理条件下,群落间相互作用加强,细菌群落内部相互作用(共311个相关中有195个正相关)增加得更为明显,显著高于细菌-真菌群落之间(共132个相关中有32个正相关)以及真菌群落内部(共12个相关中有8个正相关)的相互作用。施加生物质炭处理后,细菌群落内部以及细菌-真菌群落之间的积极联系显著增强(P < 0.05)。

|

图 2 两种处理下互作网络中相互作用的分布饼状图 Fig. 2 Pie chart of the distribution of interactions in the interaction network relative to treatment |

根据中介中心性值指标的最大值确定了关键物种。网络分析的中介中心性指标显示(图 1),对照组中介中心性指标的总体分布为0~0.27,其中起到关键连接作用的类群有细菌中的孙修勤菌(Sunxiuqinia)和真菌中的毕赤酵母(Pichia),中介中心性值分别为0.145和0.164。生物质炭组中介中心性指标的总体分布为0~0.32,其中起到关键作用的类群为细菌中的黄杆菌(Flavobacterium),中介中心性值为0.131。

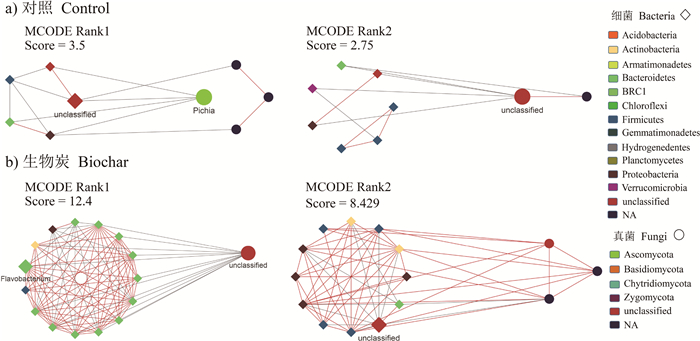

MCODE分析两种处理下的互作网络,均发现存在两个具有高度互连节点的显著聚类(图 3)。对照组中,得到的子网络的网络分数分别为3.5(节点数为9,连接数为14)和2.75(节点数为9,连接数为11),且均以细菌节点和负相互作用为主。生物质炭组中,得到的子网络的网络分数分别为12.4(节点数为16,连接数为93)和8.429(节点数为15,连接数为59),且均以正相互作用为主。关键类群中的毕赤酵母(Pichia)和黄杆菌(Flavobacterium)分别出现在对照和施加生物质炭处理的得分最高的模块化结构中。

|

图 3 两种处理下互作网络MCODE分析的子网络图 Fig. 3 Subnetwork diagram of the interaction network based on MCODE analysis relative to treatment |

利用Mantel test分析对照组和生物质炭组中植物根系(根系总长度、平均直径、平均长度、总表面积、总切面面积、平均表面积和平均切面面积)、土壤物理结构(比表面积、微孔面积、外表面积和微孔体积)以及土壤环境因子(pH、铵态氮、硝态氮和有效磷)对根际土壤细菌-真菌之间相互作用(互作网络中正连接数与总连接数的比值)的影响(表 2)。在对照组中,物理结构(r=0.318,P=0.001)对细菌-真菌之间相互作用表现出显著影响。施加生物质炭后,环境因子对细菌-真菌互作的影响显著改变,土壤pH(r=0.385,P=0.003)和土壤铵态氮(r=0.501,P=0.003)对细菌-真菌互作的影响显著增强。

|

|

表 2 环境因子与细菌-真菌相互作用的Mantel test分析 Table 2 Mantel test of environmental factors with the interaction between bacteria and fungi |

本研究通过构建细菌-真菌群落的互作网络(图 1),探讨了施加生物质炭对根际土壤细菌-真菌共现模式的影响。研究结果发现,微生物共现模式在施加生物质炭后显著改变(表 1),相比于未施加生物质炭的对照组,施加生物质炭后细菌与真菌之间的相互作用显著增多,互作网络的节点显著增多,网络变得更加复杂,这与Gundale和DeLuca[34]的研究结果相照应——添加生物质炭可以通过改变理化性质(如pH和持水能力等)来提高土壤养分有效性。通常,我们认为生态系统中的有效养分越丰富,微生物生态网络复杂性和稳定性也越高,群落的高稳定性是实现生态功能的重要因素[35]。此外,生物质炭的特殊孔隙结构对细菌和真菌有保护作用,能够降低竞争者对它们的侵害。本研究中,Mantel test分析(表 2)结果表明,施加生物质炭后,土壤pH(r=0.385,P = 0.003)和铵态氮(r=0.501,P=0.003)对细菌-真菌互作的影响显著增强,与Lauber等[36]的pH是调节细菌群落结构的最重要参数,而真菌群落与营养状况关系最为密切的假设一致,认为土壤酸度的改变有利于细菌的生长,而铵态氮的变化导致了真菌群落的改变,从而影响互作网络。施加生物质炭还能够促进黑麦草根系的生长,增加其生物量,同时,增强的根系产生的分泌物又可以为微生物的代谢和生长提供营养和能量,改变根际微生物与植物之间的联系,从而改变根际土壤微生物的种类和数量。

对照组的互作网络中,在细菌和真菌群落内部以及细菌和真菌之间的相互作用以负相关关系为主(图 2),表明细菌和真菌对资源存在着潜在的竞争[37]。但是,随着生物质炭的施加,分子生态网络改变,并且相互作用以正相关关系为主,尤其是细菌-真菌群落之间负相互作用的占比降低,这与Banerjee[38]的研究发现相似,添加有机物和营养物质后,细菌-真菌互作网络的正相互作用增强,细菌、真菌模块内部和细菌-真菌群落之间的负相关数量减少,这可能是因为生物质炭或者有机物及营养物质的添加丰富了群落的营养结构,缓解了竞争。

3.2 生物质炭对网络模块化结构的影响土壤生态系统中,模块化分析对于识别样本之间的微生物关联、提高其与非生物因素的相互作用的理解是非常重要的。MCODE分析两种处理下的互作网络,均发现存在两个具有高度互连节点的显著聚类,相比于对照组,施加生物质炭处理条件下互作网络的模块化结构更为复杂,具有更高的网络分数和更多的节点及相互作用,且均以细菌节点居多。这些模块并非严格遵循分类学分类,即微生物之间存在相互作用但不依赖于它们的分类,类似地,Burke等[39]对细菌群落组装的研究发现,样本间微生物物种的组成存在较大的差异,但其功能的相似性高达70%,证明了细菌群落的组装是由功能基因而非物种分类决定的,并提出具有相似营养物质或其他生态特性的物种能够占据相同的生态位的观点。本研究中,生物质炭的添加重新分配了系统资源是导致模块化模式改变的可能原因。

关键类群是微生物群落中高度连接的类群,具有特殊而重要的作用,它们的去除可引起群落结构和功能的急剧变化。Banerjee[38]研究证实土壤有机质分解率由关键类群(细菌中的酸杆菌门、弗拉特氏菌属和芽单胞菌属以及真菌中的毛壳菌属和镰刀菌属等)的丰度决定,并且在此前的研究中,Li等[40]发现在有机质含量高的土壤中,芽单胞菌门和酸杆菌门具有较高的丰度,Harreither等[41]证实子囊菌门的毛壳菌属在降解纤维素、纤维二糖和木质素等有机质方面起着关键作用,这不仅支持了关键类群对于特定生境和过程的重要性,而且为关键类群与微生物群落功能的相关性提供了证据。我们的研究发现,关键类群中的毕赤酵母(Pichia)和黄杆菌(Flavobacterium)分别出现在对照和施加生物质炭处理的得分最高的模块化结构中,这可能说明关键类群在模块化结构中同样发挥重要的连接作用。

然而,这些共现模式是统计上确定的各种OTU的相对丰度之间的关联,仅能指示潜在的正相互作用或负相互作用。在田间条件下,这些相互作用是否会发生在微观尺度上需要进一步的有针对性的研究,并且未来将增加实验来加强关于网络的动态变化和机制的研究。

4 结论施加生物质炭显著丰富了黑麦草根际土壤细菌-真菌群落的网络相互作用,加强了细菌内部以及细菌与真菌之间的积极联系。由于网络分析仅能指示微生物潜在的相互作用,同时,生物质炭、植被以及土壤的类型,生物质炭的添加量以及培养时间等因素都可能影响生物质炭与土壤根际土壤细菌-真菌群落相互作用的关系,下一步的研究将考虑上述影响。

| [1] |

Hartmann A, Rothballer M, Schmid M. Lorenz Hiltner, A pioneer in rhizosphere microbial ecology and soil bacteriology research . Plant and Soil, 2008, 312(1/2): 7-14.

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Bulgarelli D, Schlaeppi K, Spaepen S, et al. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants . Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2012, 64(1): 807-838.

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

de Menezes A B, Richardson A E, Thrall P H. Linking fungal-bacterial co-occurrences to soil ecosystem function . Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2017, 37: 135-141. DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2017.06.006

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Deveau A, Bonito G, Uehling J, et al. Bacterial-fungal interactions:Ecology, mechanisms and challenges . FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2018, 42(3): 335-352. DOI:10.1093/femsre/fuy008

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Toro M, Azcon R, Barea J. Improvement of arbuscular mycorrhiza development by inoculation of soil with phosphate-solubilizing rhizobacteria to improve rock phosphate bioavailability (32P) and nutrient cycling . Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1997, 63(11): 4408-4412.

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Sui X L, Zhang T, Tian Y Q, et al. A neglected alliance in battles against parasitic plants:Arbuscular mycorrhizal and rhizobial symbioses alleviate damage to a legume host by root hemiparasitic Pedicularis species . New Phytologist, 2018. DOI:10.1111/nph.15379

(  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Sivan A, Chet I. The possible role of competition between Trichoderma harzianum and Fusarium oxysporum on rhizosphere colonization . Phytopathology, 1989, 79(2): 198-203. DOI:10.1094/Phyto-79-198

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Ongena M, Jourdan E, Adam A, et al. Surfactin and fengycin lipopeptides of Bacillus subtilis as elicitors of induced systemic resistance in plants . Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 9(4): 1084-1090.

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Fuhrman J A. Microbial community structure and its functional implications . Nature, 2009, 459(7244): 193-199. DOI:10.1038/nature08058

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Purahong W, Wubet T, Lentendu G, et al. Life in leaf litter:Novel insights into community dynamics of bacteria and fungi during litter decomposition . Molecular Ecology, 2016, 25(16): 4059-4074. DOI:10.1111/mec.13739

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Lehmann J, Gaunt J, Rondon M. Bio-char sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems-A review . Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 2006, 11(2): 403-427. DOI:10.1007/s11027-005-9006-5

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Laird D A. The charcoal vision:A win-win-win scenario for simultaneously producing bioenergy, permanently sequestering carbon, while improving soil and water quality . Agronomy Journal, 2008, 100(1): 178-181. DOI:10.2134/agronj2007.0161

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Sohi S P, Krull E, Lopez-Capel E, et al. A review of biochar and its use and function in soil . Advances in Agronomy, 2010, 105(1): 47-82.

(  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Omondi M O, Xia X, Nahayo A, et al. Quantification of biochar effects on soil hydrological properties using meta-analysis of literature data . Geoderma, 2016, 274: 28-34. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.03.029

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Herath H M S K, Camps-Arbestain M, Hedley M. Effect of biochar on soil physical properties in two contrasting soils:An Alfisol and an Andisol . Geoderma, 2013, 209-210: 188-197. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2013.06.016

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Laird D A, Fleming P, Davis D D, et al. Impact of biochar amendments on the quality of a typical Midwestern agricultural soil . Geoderma, 2010, 158(3): 443-449.

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

He L L, Zhong Z K, Yang H M. Effects on soil quality of biochar and straw amendment in conjunction with chemical fertilizers . Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 2017, 16(3): 704-712.

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Lehmann J, Joseph S.Biochar for environmental management: Science, technology and implementation.2nd ed.London: Routledge, 2015

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Pietikäinen J, Kiikkilä O, Fritze H. Charcoal as a habitat for microbes and its effect on the microbial community of the underlying humus . Oikos, 2010, 89(2): 231-242.

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

王丹丹, 杨泽平, 赵远, 等. 生物炭对施粪肥土壤中根际真菌群落多样性及相互作用的影响. 环境科学, 2018, 39(11): 5163-5169. Wang D D, Yang Z P, Zhao Y, et al. Effects of biochar addition on the diversity and interaction of rhizosphere fungi in manure-fertilized soil (In Chinese). Environmental Science, 2018, 39(11): 5163-5169. (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Sereti I. Black carbon decomposition and incorporation into soil microbial biomass estimated by 14C labeling . Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2009, 41(2): 210-219.

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Deenik J L, Mcclellan T, Uehara G, et al. Charcoal volatile matter content influences plant growth and soil nitrogen transformations . Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2010, 74(4): 1259-1270. DOI:10.2136/sssaj2009.0115

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Lehmann J, Rillig M C, Thies J, et al. Biochar effects on soil biota-A review . Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2011, 43(9): 1812-1836.

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Steiner C, Glaser B, Teixeira W G, et al. Nitrogen retention and plant uptake on a highly weathered central Amazonian Ferralsol amended with compost and charcoal . Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 2010, 171(6): 893-899.

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Rillig M C, Mummey D L. Mycorrhizas and soil structure . New Phytologist, 2010, 171(1): 41-53.

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Warnock D D, Lehmann J, Kuyper T W, et al. Mycorrhizal responses to biochar in soil-Concepts and mechanisms . Plant and Soil, 2007, 300(1/2): 9-20.

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

鲁如坤. 土壤农业化学分析方法. 北京: 中国农业科学技术出版社, 2000. Lu R K. Analytical methods for soil and agro-chemistry (In Chinese). Beijing: China Agricultural Science and Technology Press, 2000. (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Fagerlund G. Determination of specific surface by the BET method . Materials and Structures, 1973, 6(3): 239-245.

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

周闻达, 王莹, 鲍征宇, 等. 等温吸附法在页岩孔隙结构测试中的应用. 科技通报, 2015(1): 12-18. Zhou W D, Wang Y, Bao Z Y, et al. Application of isothermal adsorption in shale pore structure test (In Chinese). Bulletin of Science and Technology, 2015(1): 12-18. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-7119.2015.01.004 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

王树凤, 胡韵雪, 孙海菁, 等. 盐胁迫对2种栎树苗期生长和根系生长发育的影响. 生态学报, 2014, 34(4): 1021-1029. Wang S F, Hu Y X, Sun H J, et al. Effects of salt stress on seedling growth and root growth of two oak species (In Chinese). Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2014, 34(4): 1021-1029. (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

顾静馨. 土壤微生物生态网络的构建方法及其比较. 江苏扬州: 扬州大学, 2015. Gu J X. The methods of constructing soil microbial ecological network and its comparison (In Chinese). Yangzhou, Jiangsu: Yangzhou University, 2015. (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Banerjee S, Baahacheamfour M, Carlyle C N, et al. Determinants of bacterial communities in Canadian agroforestry systems . Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 18(6): 1805-1816. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.12986

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Vickmajors T J, Priscu J C, Amaralzettler L A. Modular community structure suggests metabolic plasticity during the transition to polar night in ice-covered Antarctic lakes . ISME Journal, 2014, 8(4): 778-789. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2013.190

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Gundale M J, DeLuca T H. Temperature and source material influence ecological attributes of ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir charcoal . Forest Ecology and Management, 2006, 231(1): 86-93.

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Zhou J, Deng Y, Luo F, et al. Functional molecular ecological networks . mBio, 2010, 1(4): 1592-1601.

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Lauber C L, Strickland M S, Bradford M A, et al. The influence of soil properties on the structure of bacterial and fungal communities across land-use types . Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2008, 40(9): 2407-2415.

(  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Blagodatskaya Е, Kuzyakov Y. Mechanisms of real and apparent priming effects and their dependence on soil microbial biomass and community structure:Critical review . Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2008, 45(2): 115-131. DOI:10.1007/s00374-008-0334-y

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Banerjee S. Network analysis reveals functional redundancy and keystone taxa amongst bacterial and fungal communities during organic matter decomposition in an arable soil . Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2016, 97: 188-198.

(  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Burke C, Steinberg P, Rusch D, et al. Bacterial community assembly based on functional genes rather than species . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(34): 14288-14293. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1101591108

(  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Li F, Chen L, Zhang J, et al. Bacterial community structure after long-term organic and inorganic fertilization reveals important associations between soil nutrients and specific taxa involved in nutrient transformations . Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00187

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Harreither W, Sygmund C, Augustin M, et al. Catalytic properties and classification of cellobiose dehydrogenases from ascomycetes . Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(5): 1804-1815. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02052-10

(  0) 0) |

2. State Key Laboratory of Soil and Sustainable Agriculture, Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China

2019, Vol. 56

2019, Vol. 56