2. 广东省科学院广东省生态环境与土壤研究所广东省农业环境综合治理重点实验室, 广州 510650;

3. 华南师范大学环境研究院, 广东省化学品污染与环境安全重点实验室, 广州 510006;

4. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

5. 华南土壤污染控制与修复国家地方联合工程研究中心, 广州 510650

2. Guangdong Key Laboratory of Integrated Agro-environmental Pollution Control and Management, Institute of Eco-environmental and Soil Sciences, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China;

3. Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Chemical Pollution and Environmental Safety, Environmental Research Institute, South China Normal University, Guangzhou 510006, China;

4. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

5. National-Regional Joint Engineering Research Center for Soil Pollution Control and Remediation in South China, Guangzhou 510650, China

土壤酸化与重金属污染共存叠加,引起土壤镉有更强的移动性,相应地提高农作物等植物对镉的吸收累积[1-3]。水稻和小麦等成为我国重金属超标最严重的粮食作物,比如稻米镉超标率高达12.8%,污染区域居民镉摄入量已经超过了世界卫生组织WHO的限值,其中稻米镉贡献了总摄入量的56%[4],因而严重威胁着当地居民的身体健康[5]。镉超积累植物如龙葵、伴矿景天等在镉污染土壤具有高效地吸收和累积镉的潜能,使得其在土壤植物修复中能够被广泛应用[2-3]。因此,阐明土壤-植物体系镉的迁移转化机制,一方面对于理解和降低农作物如小麦、大麦和水稻对镉的吸收、转运和储存具有重大作用,另一方面有助于提高土壤镉污染超积累植物吸取修复效果。

自然环境中,镉元素只有一个氧化态,主要以+2价形式存在,其地球化学行为与锌类似,属亲硫元素。地壳中镉存在8个稳定同位素:106Cd(1.25%)、108Cd(0.89%)、110Cd(12.50%)、111Cd(12.80%)、112Cd(24.13%)、113Cd(12.20%)、114Cd(28.73%)和116Cd(7.50%)[6]。同位素分馏即为两个库之间的同位素组成差异,通常以114Cd/110Cd表示镉同位素组成的质量变化,且分异过程主要受动力学效应和热力学效应(平衡效应)的影响。随着分离纯化技术方法的改善和标准物质的不断推进,以及多接收器电感耦合等离子体质谱仪的发展,镉稳定性同位素组成的分析测定变得更加精确[7]。

非传统稳定性同位素(如铜、铁、锌和镉等重金属)研究已成为地球科学领域的重要研究方向,为阐明金属元素在环境中迁移转化过程和机制提供了一种全新的技术手段[7-10]。随着铜、锌、汞和铁同位素分馏应用于植物对(类)金属的吸收、转运和累积机制[8-9, 11-12],土壤-植物体系镉同位素分馏也成为环境地球化学关注的热点。镉从土壤固相向水相溶解释放Cd2+的过程优先选择重镉同位素,其分馏程度∆114/110Cdsolution-soil达到0.39‰~0.79‰[13-14]。而水钠锰矿则倾向于吸附轻镉同位素,且在低离子浓度下较高离子浓度下的镉同位素分馏值小,分别为∆114/110Cdfluid-solid = 0.24‰ ± 0.06‰(1 sd)和0.54‰ ± 0.07‰(1 sd)[15]。次生矿物硫化镉的形成、镉与方解石的共沉淀过程均导致固相富集轻镉同位素[16-17]。镉超积累和耐受性植物包括龙葵(Solanum nigrum)、蓖麻(Ricinus communis)等相比于培养液倾向富集轻镉同位素[18-20],证实了植物体对镉的吸收过程主要为Cd2+形式,且受根部离子扩散过程控制[21]。小麦也倾向于从Ca(NO3)2提取的有效Cd库吸收轻镉同位素(∆114/110Cdwheat-extract = -0.21‰~0.03‰)[13]。镉从根系木质部装载并随蒸腾流转运至叶片[20],在向上长距离转运过程中镉会被茎叶累积,使镉在水稻根和茎叶的同位素组成产生差异(∆114/110Cdstraw-root = 0.21‰~0.41‰)[13]。镉的向上转运过程即为镉在各组织部位的配体交换,受含硫配体如植物螯合肽(Phytochelatin,PCs),谷胱甘肽(Glutathione,GSH)以及含氧配体如2’-脱氧麦根酸(2’-Deoxymugineic acid,DMA)、尼克酰胺(Nicotinamide,NA)和低分子有机酸等的影响[22]。小麦的籽粒和茎叶之间镉同位素分馏∆114/110Cdgrain-straw为0.10‰~0.51‰[13]。该过程与含硫配体如植物螯合肽或谷胱甘肽等对于轻镉同位素的扣押累积有关,相应地游离态Cd2+或者含氧官能团的配体等重Cd同位素继续向籽粒转运[13-14, 23]。

基于此,本文主要从土壤-植物体系镉的同位素分馏角度出发,着重阐述土壤镉的环境化学行为以及植物对镉的吸收、转运和累积机制,以期为镉污染土壤的农作物减毒脱毒和植物修复提供理论基础和科学依据。

1 镉同位素分馏 1.1 镉同位素分析方法镉同位素分析的前处理主要分为消解和纯化两个过程。前者主要通过二次蒸馏的硝酸、盐酸和氢氟酸于消解罐内处理土壤和植物样品,后者是指通过阴离子交换树脂结合一系列稀释处理的酸分离纯化,以防止杂质干扰同位素的测定。Wombacher等[24]采用Biorad AG1-X8和Eichrom TRU Spec树脂双柱法先后去除样品中大部分基质和Sn,并利用6 mol·L-1 HNO3洗脱获取纯净的镉。Cloquet等[6]利用AG-MP1离子交换树脂,依次使用高浓度至低浓度的HCl,相继去除基质和Zn,最终采用0.0012 mol·L-1 HCl洗脱获取镉。目前,为提高镉同位素的分析测试精度,一般采用双稀释剂法,即往样品加入一定量111Cd-113Cd双稀释剂。如Imseng[25]和Wiggenhauser[26]等往已消解样品中加入适量的111Cd-113Cd双稀释剂并使其充分混合平衡。Liu等[27]同样采用双稀释剂法,将111Cd-113Cd双稀释剂加入以6 mol·L-1 HCl为介质的样品中,于电热板120 ℃下加热平衡过夜。随即装载AG1-X8阴离子交换树脂(100~200目),并依次使用6 mol·L-1 HCl、0.3 mol·L-1 HCl和0.5 mol·L-1 HNO3+0.1 mol·L-1 HBr去除样品大部分基质以及Pd、In、Zn和Sn,最终使用2 mol·L-1 HNO3洗脱获得纯化的镉。该方法的建立一定程度上克服了分析技术的难度,进一步推动镉同位素分馏手段的运用。

同位素分馏数值δ则将样品同位素比值和标准物质比值标准化,通常用如下的形式来表示样品的镉同位素组成δ114/110Cd:

| $ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{114/110}}{\rm{Cd}} = [{^{114}}{\rm{Cd}}{/^{110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{sample}}}}/{^{114}}{\rm{Cd}}{/^{110}}{\rm{Cd}}}\\ {_{{\rm{standard}}} - 1] \times 1000} \end{array} $ | (1) |

镉同位素标样问题,同样限制了镉同位素方法的建立和推广。在2005-2013年期间,Cd同位素的标准溶液并不统一,主要包括JMC[28]、Spex[6]、Prolabo[6]、JMC Münster[29]、PCIGR-1等Cd标准液[30]。自Abouchami等[31]进一步提倡采用NIST SRM 3108作为标样后,2016-2018年期间镉同位素标准物质基本为NIST SRM 3108,并作为一级标准物质[32]。虽然前期的镉标准物质存在不统一的现象,但均可根据式(2)进行转换计算,因此一定程度上弥补了不同标准物质引起的结果不统一的缺陷。

| $ \begin{array}{l} {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{{\rm{114/110}}}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{x}} - {\rm{a}}}} = \frac{{({{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{{\rm{114/110}}}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{x}} - {\rm{a}}}})({{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{{\rm{114/110}}}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{x}} - {\rm{a}}}})}}{{1000}}\\ + {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{{\rm{114/110}}}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{x}} - {\rm{b}}}} + {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{{\rm{114/110}}}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{b}} - {\rm{a}}}} \end{array} $ | (2) |

式中,X代表样品,a和b分别表示不同的镉同位素标准物质[33-34]。

两个库存之间的镉同位素分异程度可表示为∆114/110CdA-B:

| $ \begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{\Delta ^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{A - B}}}}}:\\ {{\Delta ^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{A - B}}}} = {\rm{ }}{{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{\rm{A}}} - {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{\rm{B}}}} \end{array} $ | (3) |

1)动力学分馏效应。稳定同位素分馏分为质量分馏和非质量分馏。其中质量分馏又分为动力学分馏和平衡分馏效应两种。前者主要由于质量差异引起的不同反应速率,包括离子扩散和微生物介导还原过程引起的共沉淀作用。瑞利分馏模型(Raleigh model)适用于封闭体系中不完全的单向反应(或逆向反应速率可忽略不计),可用于描述封闭系统中反应阶段同位素比值的演化,具体表现出反应库为均匀混合体系,并连续不断地优先迁移轻同位素的动力学控制体系[7]。该模型可以确定特定过程的分馏系数或根据某一相中同位素组成获得转化过程的程度,以及根据质量平衡,某一相中元素的剩余百分数可知两相同位素组成。具体瑞利分馏模型可用下面两个公式表示:

| $ {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}_R} = {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}_0} + {\rm{ \mathsf{ ε} ln}}F $ | (4) |

根据质量守恒关系δ0=δR×F + δP×(1-F),可得到生成池P的同位素组成为:

| $ {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}_{\rm{P}}} = {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}_0} + {\rm{ \mathsf{ ε} ln}}F - {\rm{ \mathsf{ ε} ln}}F/1 - F $ | (5) |

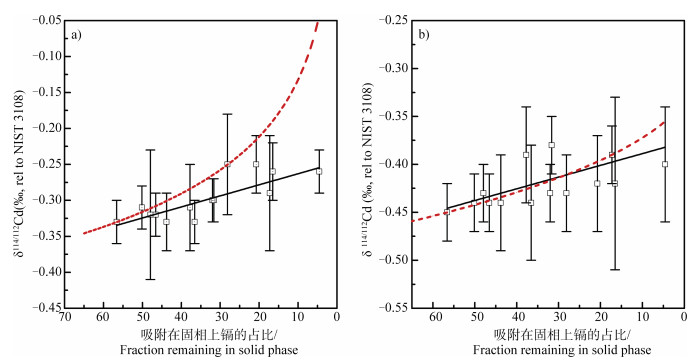

式中,δR、δP和δ0分别表示某时刻反应池、生成池和初始反应池中镉元素的同位素组成;F为保留在反应池中的某元素的分数,ε为同位素分馏系数。瑞利分馏模型能够定量研究镉同位素的过程分馏,通过获取反应过程的镉同位素分馏常数/富集系数(ε),即可知反应进行或者迁移转化的程度[7]。目前,土壤-植物体系中涉及瑞利分馏模型的有土壤老化过程[25],吸附过程[15],植物体内转运过程[13]。以低离子强度条件下水钠锰矿对镉的吸附实验研究为例[15],由水相和固相中镉同位素组成δ114/112Cd和溶液镉剩余分数的结果(图 1)可见,分馏常数ε为0.12‰,且在获取同位素数据的情况下,即可量化转化过程的程度。

|

注:误差棒代表每个样品3或4次分析结果得出的2sd,实线代表平衡分馏封闭系统拟合,虚线代表分馏系数ε =0.12‰的瑞利分馏拟合。 Note: The error bars represent 2 sd of 3 or 4 rounds of test of each sample; the solid lines do fitting of a closed equilibrium fractionation system, while the dashed lines do fitting of Rayleigh fractionation with ε=0.12‰. 图 1 低离子强度下水钠锰矿吸附镉后水相(a)和固相(b)中镉的同位素组成[15] Fig. 1 Cd isotopic compositions in Birnessite in fluid(a)and solid phase(b)after Cd adsorption under low ionic strength[15] |

2)平衡分馏效应。同位素的平衡分馏效应表现为两相以相同速率进行正向和反向反应。平衡分馏主要以配位鳌合过程为主,在同位素分馏达到平衡时,重同位素在“更强的结合环境”中富集[35]。通常,对于同一种金属不同配位螯合态物种而言,配位数较低和键长较短的配体,由于其“较强的键环境”而倾向于富集较重的同位素[14]。比如镉与含氧有机质鳌合(即Cd-O),以及与含硫有机质螯合时(即Cd-S)的键长分别为2.29 Å ~2.31Å和2.47 Å~2.54 Å[36-37]。相应地,镉与含氧有机质配位螯合时,则倾向于富集重镉同位素;而与含硫有机质配位螯合时,则优先选择轻镉同位素[23, 38-39]。

2 土壤镉同位素分馏的关键过程土壤中可以导致镉发生同位素分馏的过程很多,目前报道的主要包括:溶解过程、共沉淀过程、吸附过程和有机质螯合过程等四个方面。这些过程均能够影响土壤中镉的生物有效性。

2.1 溶解过程目前基于溶解过程引起镉同位素发生分馏的研究报道,主要涉及母质矿物/土壤到浸出液、从底泥至河水等过程、土壤剖面差异比较,以及包括从母质矿物到土壤的风化过程[25, 32, 40-41]。溶解过程可导致重镉同位素的优先释放。Zhang等[41]研究表明,Pb-Zn矿石的浸出液相比于初始矿石和残渣均呈现重镉同位素组成的特征,分别为∆114/110Cdleachate-initial state=0.40‰~0.50‰和∆114/110Cdleachate-residual state= 0.36‰~0.53‰;进一步对河堤土壤和风化淋滤后的河流底泥中镉同位素的分析发现,二者的同位素分馏值均为∆114/110Cdstream sediment-soil = 0.50‰,这表明风化淋滤过程是导致自然界中镉同位素分馏的原因之一。Imseng等[25]发现渗流水对于土壤的渗滤过程可引起富集更重的镉同位素,导致整体土壤镉的同位素更轻。其同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdseepage water-soil= 0.59‰~0.69‰,这也支持了溶解过程可引起重镉同位素的优先释放。Wiggenhauser等[13]研究指出,与深层土壤(C horizon)相比,表层土壤(A horizon)的总镉同位素组成呈现更重的同位素特征,同位素分馏值∆114/110CdA horizon-C horizon在0.03‰~0.12‰的范围,证实自然风化过程产生一定的镉同位素分馏。作者进一步对表层土采用Ca(NO3)2提取生物有效态镉,发现提取液生物有效态镉和土壤总镉的同位素组成之差∆114/110Cdextract-A horizon在0.16‰~0.43‰的范围,这说明相比于整体土壤,土壤有效态的镉同位素组成更重。

2.2 共沉淀过程土壤在淹水管理模式下,镉的生物有效性和毒性显著降低[36, 42-43],与厌氧还原条件驱动SO42-等硫素的还原,生成对镉具有很强键合能力的H2S,进而促进镉与硫化物发生共沉淀生成含镉硫化物(CdS)有关[42]。厌氧条件下,CdS的形成倾向于富集轻镉同位素。与多价态金属如Fe同位素相比,镉往往表现出更小的同位素分馏尺度[7]。类似于锌同位素,低pH条件下锌以硫化物形式沉积时,锌几乎不发生同位素分馏;当pH提高至9时,∆66/64ZnZn(aq)-ZnS = 0.6‰[44]。Guinoiseau等[17]发现,在CdS形成过程中,其分馏尺度受盐度的影响,分馏常数α112/110CdCd(aq)-CdS(α = 112/110RCd(aq)/112/110RCdS,R为同位素比值)随着盐度的提高而降低:纯水条件下α = 1.00026;当盐度提高至海水盐度的两倍时,α值降低至1.00014。相似地,Xie等[45]报道CdS的形成过程遵循Rayleigh分馏模型,分馏常数α114/110Cdseawater-CdS为1.00029。此外,镉与方解石发生共沉淀作用时,海水盐度条件下也偏向于选择轻镉同位素,分馏系数αCaCO-Cd(aq)为0.99955 ± 0.00012,且纯水条件下不存在镉同位素分馏(2sd范围内),即αCaCO-Cd(aq) = 1.0000 ± 0.0001[16]。

2.3 吸附过程铁锰(氢)氧化物对镉具有很强的吸附能力,可降低土壤有效态镉的含量[46]。研究表明,在调控土壤镉有效性的众多过程中,铁锰氧化物对镉的吸附/解吸作用比CdS的共沉淀/释放作用更重要[47]。即使在厌氧还原条件下铁锰矿物的还原溶解可导致镉的释放,但相比于原生铁锰矿物,次生铁锰矿物能更有效地吸附镉,从而抑制镉的释放[48]。通常,吸附过程引起的镉同位素分馏基于质量平衡,在已知初始物质同位素组成和各相占比的情况下,仅需分析液相或者固相中某一相的镉同位素组成,即可获得另一相的同位素组成。因此,通过瑞利分馏模型获得吸附过程的同位素分馏系数对于追踪镉吸附程度十分重要[7]。Wasylenki等[15]发现水钠锰矿倾向于吸附轻镉同位素,相似的结果同样发生在黏土矿物对镉的吸附上[16],而次生铁矿物吸附导致的镉同位素分馏尚无报道。相反,通过对锌内圈螯合的无定型二氧化硅(∆66/64Znaqueous-sorbed=-0.94‰ ± 0.11‰)相比于石英(∆66/64Znaqueous-sorbed = -0.60‰ ± 0.11‰)更加倾向于吸附重锌同位素[49]。因此,通过镉同位素分馏尺度变化,可以鉴别镉在吸附剂的结合方式,这对于进一步评估镉固化效果以及识别微界面镉的环境化学行为具有重要作用。

2.4 有机质螯合配位过程土壤有机质是影响镉地球化学行为的关键因素,可通过螯合配位作用与镉形成配合物[50-51],其中土壤有机质含S供体可能是土壤中Cd的主要结合位点[52]。螯合配位过程导致的金属元素同位素分馏主要由不同有机质中特定官能团对金属的键合常数差异,即配位环境键强差异引起[7]。目前,对于有机质螯合配位过程镉同位素分馏的研究较少,对其他金属元素的研究较多。研究结果表明,有机质与Fe、Zn和Cu等二价金属配位螯合时均倾向于键合重同位素,同位素分馏程度分别为∆56/54FeFe-desferrioxamine B/Fe-oxalate= 0.20‰±0.11‰,∆66/64Znpurified humic acid-Free Zn= 0.24‰±0.06‰和∆65Cuinsolubilized humic acid-solution=0.26‰± 0.11‰[12-14, 23, 53-55]。因此,许多学者推断,含氧官能团的有机质对镉的键合倾向于富集重镉同位素。Wei等[20]在水培液中添加乙二胺四乙酸(EDTA),发现EDTA可降低超积累植物龙葵和耐受性植物蓖麻对镉的吸收积累,并导致植株内富集更轻的镉同位素,这侧面证实了在水培液中,与自由镉离子Cd2+相比,EDTA-镉螯合物倾向富集重镉同位素。相反地,含硫官能团的有机质对金属元素的螯合配位过程可导致螯合物富集轻同位素,如:Hg-巯基有机化合物的∆202Hgthiol bound Hg-HgCl2/Hg(OH)2 = -0.53‰~-0.62‰ [35];Horner等[38]研究进一步证实了含巯基化合物偏向于键合轻镉同位素的特征(∆114/110 CdCd ligand-growth medium = -0.67‰ ± 0.07‰)。

3 植物中镉同位素分馏机制最初,稳定同位素分馏技术作为一种土壤-植物体系中元素生物地球化学过程的研究手段,主要用于示踪植物对金属元素如铜、锌、汞和铁的吸收、转运和累积过程[8-9, 12, 53]。由于镉污染引起的食品安全与生态风险问题日益严重,目前镉同位素分馏已成为环境地球化学、环境科学、生态学等领域的研究热点。现有的研究主要关注两大类植物:一为农作物[12-13, 23];二为超积累植物和耐受性植物[18-20, 56]。其中,农作物包括小麦和大麦等;镉超积累植物包括龙葵等;镉耐受性植物包括蓖麻等,这些植物均能够有效/高效吸收积累镉。

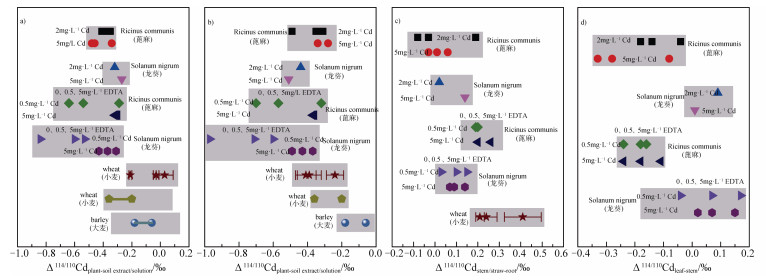

土壤溶液(或孔隙水)中的自由镉离子Cd2+被认为是植物根部吸收镉的主要形态[20]。研究表明,无论是农作物,还是超积累植物或耐受性植物,主要表现出从有效库中吸收轻镉同位素的倾向性。Imseng等[25]对土壤-小麦/大麦体系镉同位素分馏的研究表明,小麦和大麦整体植株与土壤溶液之间的同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdplant-soil solution =-0.06‰~-0.36‰(图 2a)。虽然小麦在三种不同土壤中的镉同位素分馏规律不尽相同,小麦与土壤有效态镉之间的分馏∆114/110Cdwheat-extract在-0.21‰~0.03‰的范围内,其中存在没有发生分馏的现象[13]。龙葵和蓖麻与其水培液之间的镉同位素分馏∆114/110Cdplant-solution分别为-0.46‰~-0.27‰和-0.48‰~-0.41‰(图 2a)[17]。

|

图 2 植物镉同位素分馏汇总(a)整体植株与土壤有效态/培养液之间的镉同位素分馏;(b)根部与土壤/培养液之间的镉同位素分馏;(c)地上部与根部之间的镉同位素分馏;(d)叶与茎部之间的镉同位素分馏[13-14, 19-20, 23] Fig. 2 Summary of Cadmium isotopic fractionation between: (a)between the whole plant and soil available fraction/ culture solution; (b)between root and soil/culture solution; (c)between above ground tissues and root; and(d)between leaf and stem [13-14, 19-20, 23] |

土壤溶液中镉的有效性受铁锰氧化物、硫化镉、有机质等因素的影响。如上所述,水钠锰矿对镉离子的吸附作用,以及硫化物对镉的共沉淀作用,均能够富集轻镉同位素到铁锰氧化物和硫化物中[15-17],进而影响植物吸收过程中镉同位素分馏。Wei等[19]通过水培实验研究镉胁迫下施加0、0.5和5 mg·L-1 EDTA时,龙葵与培养液之间的镉同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdplant-solution分别为-0.53‰,-0.60‰和-0.84‰;而蓖麻的∆114/110Cdplant-solution分别为-0.29‰、-0.54‰和-0.64‰,表明培养液中有机质是影响土壤有效态镉以及植物对镉吸收的重要因素。此外,Wiggenhauser等[13]和Imseng等[25]推测,土壤质地、有机质含量(SOC)、阳离子交换量(CEC)和pH等也可能影响镉在土壤固液两相分配平衡和土壤溶液中的化学形态,进而影响植物有效态镉的占比,从而影响平衡分馏的程度。

3.1 根部吸收过程在土壤-植物体系中,植物根部吸收镉过程主要富集轻镉同位素。Wiggenhauser等[13]研究报道小麦根部与土壤有效态之间的镉同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdroot-extract为-0.41‰~-0.24‰,见图 2b。植物根部对镉的吸收由非生物过程和生物过程共同驱动。非生物过程包括镉在土壤和根部表面的扩散、吸附和共沉淀等过程。据报道,轻镉同位素比重镉同位素扩散速度快,导致植物根部表面可能累积更多轻镉同位素[57];这类似于扩散过程是导致高等植物富集轻锌同位素[9]。低镉浓度扩散过程引起的镉同位素分馏尺度比高浓度更大,低镉浓度下水培种植的蓖麻和龙葵根部与培养液之间的镉同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdroot-solution分别为-0.70‰~-0.32‰和-0.97‰~-0.60‰,高浓度下则为-0.37‰~-0.36‰和-0.49‰~-0.36‰[20]。根表吸附对于镉向根部转运起到中转作用,是促使根部相比于土壤溶液富集轻镉同位素的关键环节,有利于轻镉同位素向植株体内转运[14]。

植物根部吸收镉的生物过程包括:离子通道、细胞质膜内外的电化学势差、转运蛋白等三个途径[19]。其中,离子通道和电化学势差为低亲和力转运过程,与扩散系数有关,且倾向于富集轻镉同位素[19]。相反,转运蛋白为高亲和力转运过程,其作用效果与转运蛋白的官能团有关[58]。比如NRAMP5(natural resistance-associated macrophage protein)转运蛋白内含蛋氨酸底物,其硫基官能团对镉的转运具有重要作用[59]。据研究报道证实由于NRAMP5转运蛋白的作用,促使可可豆植物体与培养液之间的分馏∆114/110Cdplant-solution达到-0.22 ± 0.08‰[60]。

3.2 向地上部转运过程根据现有的研究报道,与根部镉同位素组成相比,小麦、龙葵和蓖麻等植物的地上部组织均偏向于富集重镉同位素[13, 19-20]。其中,小麦秸秆与根部的镉同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdstraw-root为0.21‰~0.41‰[13];龙葵和蓖麻的地上部与根部的镉同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdshoot-root分别为0.13‰~0.16‰和0.18‰[19]。镉在植物体内的转运以生物过程控制为主,包括液泡隔离与木质部装载等过程[20]。以根部为例,液泡隔离主要是指镉在根部细胞质中与谷胱甘肽、金属硫蛋白以及植物螯合肽等含巯基化合物发生螯合,并转运到液泡中隔离的过程[38]。这一过程倾向于富集轻镉同位素[13, 23],因此更有利于重镉同位素向地上部转运。此外,当镉被液泡膜的载体蛋白转运到细胞外时,载体蛋白可能倾向于与重镉同位素共价键合,而残留轻镉同位素在根部液泡内[22]。木质部装载是导致镉向地上部转运的关键,且主要经共质体和质外体两个途径转运进入木质部[61]。在共质体途径中,细胞质的镉能够与含氧、硫等配体形成配合物,这些配合物可通过载体蛋白(Heavy Metal ATPase 2,HMA2)装载进入木质部;在质外体途径中,游离态镉离子可以直接进入木质部[62-66]。上述不同形态的镉在蒸腾流驱动力作用下经木质部长距离转运至地上部[22, 62, 67-68]。因此,镉从根部至地上部的转运过程产生的分馏特征受具体的镉形态及其比例的影响。

镉通过木质部随蒸腾流进入叶片的过程中,首先会由于茎部对镉的截留而导致叶片和茎部之间产生同位素分馏[12]。目前这方面的研究以超积累植物和耐受性植物为主,而针对农作物的相关研究比较缺乏。龙葵和蓖麻的叶与茎之间的镉同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdleaf-stem分别为0.01‰~0.09‰和-0.33‰~-0.04‰[19]。相似地,施加不同浓度EDTA的情况下,龙葵和蓖麻的叶与茎之间的镉同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdleaf-stem分别为-0.04‰~0.17‰和-0.24‰~-0.11‰,见图 2c[20]。在茎与叶之间的转运过程,超积累植物龙葵表现出倾向于转运重镉同位素或者不发生分馏,而耐受性植物蓖麻则选择转运轻镉同位素,这说明两者在茎和叶间的传输机制可能存在差异[18]。首先,超积累和耐受性植物茎部对镉的扣押累积主要发生在茎部液泡和细胞壁,且与镉配体的种类和比例有关[69]。通常,镉在液泡中主要与含硫的植物螯合肽或者谷胱甘肽螯合,而镉在细胞壁中主要与含氧配体螯合[12, 70]。超积累植物体内含氧配体占比较高,而耐受性植物体内以含硫配体为主[71]。因此,镉从茎部转运至叶部的过程中,超积累植物主要以较重的含氧配体螯合物为主,而耐受性植物则以较轻的含硫配体螯合物为主,从而导致两者在茎与叶之间的镉同位素分馏方向相反(如图 3)。

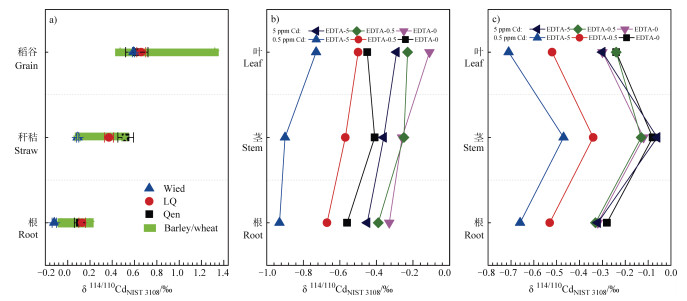

|

图 3 小麦(a)、超积累植物龙葵(b)和耐受性植物蓖麻(c)不同部位的镉同位素组成[13-14, 20] Fig. 3 Isotope composition of the cadmium in root, straw and grain of wheat(a), in root, stem and leaf of solanum nigrum(b), a Cd hyperaccumulator plant, and of ricinus communis(c)a Cd tolerant plant [13-14, 20] |

现有研究表明,农作物中镉从茎叶向籽粒的转运主要倾向于重镉同位素[13, 23, 25],如小麦籽粒与秸秆之间的镉同位素分馏为0.10‰~0.50‰[13, 23]。籽粒对镉的累积主要通过韧皮部转运过程实现[72]。含巯基官能团的有机配位化合物,如半胱氨酸、谷胱甘肽、植物螯合肽和金属硫蛋白等在茎和叶片对镉的配位螯合过程导致茎叶富集轻镉同位素。而相对更重的镉,如自由态镉离子或者与低分子含氧有机酸螯合配位的镉,则通过韧皮部向上转移至籽粒[73-74],这与主要依赖于含巯基配合物长距离转运的积累植物甘蓝型油菜不同[75]。

3.4 植物不同部位间镉同位素分馏的趋势据Wiggenhauser等[13, 23]研究报道,小麦根部、秸秆和籽粒的镉同位素组成δ114/110Cd值依次增大(-0.12‰~0.13‰,0.09‰~0.52‰和0.59‰~0.66‰,见图 3a所示)。相似的结果同样出现在大麦植株中[25]。小麦植株内部呈现出根部-秸秆-谷粒依次转运较重镉同位素,储存较轻镉同位素[13, 23, 25]。根部积累轻镉同位素与植物螯合肽等含巯基官能团有机化合物有关[76];而蒸腾作用下,镉随木质部进入秸秆,并经韧皮部转运至籽粒[69]。而超积累植物龙葵植株中δ114/110Cdleaf≥δ114/110Cdstem≥δ114/110Cdroot(图 3c),这说明在镉胁迫下植物对镉同位素产生动力分馏,不同植物的组织对镉的供应限制不同,决定了植物对镉的耐受性不同[18-20]。

植物内部镉跨组织传输和贮存的同位素分馏行为,符合封闭条件下的瑞利分馏模型拟合。Wei等[20]对蓖麻和龙葵的镉同位素分馏研究,如式(6)和式(7)所示,指出镉在植物体内的同位素分馏值可表示为∆114/110Cdroot-plant=0.0627lnFroot-0.025(R2=0.9759)和∆114/110Cdshoot-plant=-0.087lnFshoot+0.0097(R2=0.9533),表明镉根部和地上部与植物间的镉同位素分馏系数ε相反。其中根部镉剩余百分数Froot越高,根部与植物间的同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdroot-plant越大,地上部镉剩余百分数越高,则其与植物间的同位素分馏值∆114/110Cdshoot-plant越小。

| $ {\Delta ^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{root - plant}}}} = \\{\delta ^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{root}}}} - {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{plant}}}} = {\Delta ^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{translocation}}}}{\rm{ln}}{{\rm{F}}_{{\rm{root}}}} $ | (6) |

| $ {\Delta ^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{shoot - plant}}}} = \\{{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{shoot}}}} - {{\rm{ \mathsf{ δ} }}^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{plant}}}} = {\Delta ^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{translocation}}}}{\rm{ln}}{{\rm{F}}_{{\rm{shoot}}}} $ | (7) |

因而,植物体内不同部位库间镉的转运行为可用封闭系统动力学来描述,Wiggenhauser等[13]研究报道小麦各部位镉池间的转运行为如下式所示:

| $ {\Delta ^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{sink - source}}}} = {\rm{ }}{\Delta ^{114/110}}{\rm{C}}{{\rm{d}}_{{\rm{retained - mobile}}}}{\rm{ln}}(f) $ | (8) |

式中,f为sink与source的比值,其中sink、source分别代表谷粒和整体植株时,可得y=-0.35lnf-0.24(分馏系数ε= -0.35),当sink、source分别代表谷粒和地上部时y= -0.46ln(f)-0.37(分馏系数ε= -0.46),表明source对镉的贮存与sink和source之间的镉同位素分馏有关。

4 展望随着分析纯化方法和仪器设备的发展,稳定同位素分馏技术在示踪土壤-植物体系中金属元素迁移转化过程的应用,已逐步成为土壤学领域探索元素生物地球化学机制的重要方法。目前,国际上在土壤-植物体系镉同位素分馏特征和机制领域的研究才刚起步,还存在很多尚未阐明的过程与机制,而未来的研究可着眼于:

1)镉在土壤中的分馏特征受多过程、多因素等在不同尺度上的影响,包括不同土壤组分(层状硅酸盐黏土矿物、铁锰铝氧化物等)的吸附沉淀、不同有机质组分(含硫/氧配体、溶解态/固态腐殖质等)的螯合吸附、硫素氧化还原、铁锰氧化物的还原溶解与次生矿物形成等过程,且受不同母质发育土壤类型、植物根系作用(如根系分泌物、根系泌氧、根表铁膜形成等)、土壤微生物作用等因素的影响。深入研究上述过程在土壤镉迁移过程中引起的镉同位素分馏特征,有助于阐明不同环境条件下关键土壤过程导致的镉环境行为及其机制。

2)不同种类的肥料(如腐殖质类有机质、磷肥等)、环境友好型钝化剂(如生物炭、铁基材料等)的施加,是增加土壤肥力和调控重金属污染土壤安全利用的重要农艺措施。以腐殖质类有机质为例,其对镉的调控途径存在多样性:一方面有机质对于镉的螯合过程可抑制镉的有效性;另一方面低分子有机酸可活化土壤镉,这两个过程均可改变土壤有效态镉的同位素特征。针对土壤-农作物体系,结合运用镉同位素分馏方法,有助于深入探讨有机质施加对土壤镉钝化/活化过程所引起的植物体内镉吸收转运机制的改变,从而为降低农作物镉累积或者提高植物修复效率提供科学依据。

3)镉在不同类型植物体内的转运受不同镉相关基因/蛋白的调控,且在不同生长时期会存在镉再分配等过程,这些空间和时间尺度上的变化,都可能改变植物体内各部位之间镉同位素分馏的尺度。以水稻为例,OsNRAMP5、OsHMA3、OsHMA2或OsLCT1等关键转运蛋白在水稻体内镉吸收转运过程中会产生哪些镉同位素分馏的变化,其在水稻全生育期中不同时期的分馏特征如何,值得探讨。同位素分析技术与Cd形态分析(如同步辐射等)技术手段相结合,有利于从不同镉形态、不同赋存部位、不同功能蛋白、不同转运过程等方面更为准确地阐明镉在植物体内的转运和解毒机制。

4)不同营养元素(如铁、锌、硅等)的作用下可降低水稻等植物对镉的吸收、转运和累积,三者对镉在水稻体内积累过程可能存在不同的拮抗机制。因此,综合运用镉/铁/锌等同位素分馏技术、植物关键功能基因/蛋白等生理代谢机制研究方法,可从同位素分馏行为与植物生理行为等不同角度,深入揭示铁/锌/硅等营养元素对镉在植物体内迁移过程的拮抗或解毒机制。

| [1] |

Zhao F J, Ma Y B, Zhu Y G, et al. Soil contamination in China: Current status and mitigation strategies[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(2): 750-759.

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Huang R, Dong M L, Mao P, et al. Evaluation of phytoremediation potential of five Cd(hyper) accumulators in two Cd contaminated soils[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 721: 137581. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137581

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Zhou Z Q, Chen Z Z, Pan H J, et al. Cadmium contamination in soils and crops in four mining areas, China[J]. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 2018, 192: 72-84. DOI:10.1016/j.gexplo.2018.06.003

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Song Y, Wang Y B, Mao W F, et al. Dietary cadmium exposure assessment among the Chinese population[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(5): e0177978. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0177978

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Hu Y A, Cheng H F, Tao S. The challenges and solutions for cadmium-contaminated rice in China: A critical review[J]. Environment International, 2016, 92/93: 515-532. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2016.04.042

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Cloquet C, Rouxel O, Carignan J, et al. Natural cadmium isotopic variations in eight geological reference materials(NIST SRM 2711, BCR 176, GSS-1, GXR-1, GXR-2, GSD-12, Nod-P-1, Nod-A-1) and anthropogenic samples, measured by MC-ICP-MS[J]. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research, 2005, 29(1): 95-106. DOI:10.1111/j.1751-908X.2005.tb00658.x

(  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Wiederhold J G. Metal stable isotope signatures as tracers in environmental geochemistry[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(5): 2606-2624.

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Yin R S, Feng X B, Meng B. Stable mercury isotope variation in rice plants(Oryza sativa L.) from the Wanshan mercury mining district, SW China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(5): 2238-2245.

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Arnold T, Kirk G J D, Wissuwa M, et al. Evidence for the mechanisms of zinc uptake by rice using isotope fractionation[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2010, 33(3): 370-381.

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Arnold T, Markovic T, Kirk G J D, et al. Iron and zinc isotope fractionation during uptake and translocation in rice(Oryza sativa) grown in oxic and anoxic soils[J]. Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 2015, 347(7/8): 397-404.

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Ryan B M, Kirby J K, Degryse F, et al. Copper speciation and isotopic fractionation in plants: Uptake and translocation mechanisms[J]. New Phytologist, 2013, 199(2): 367-378. DOI:10.1111/nph.12276

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Tang Y T, Cloquet C, Deng T H B, et al. Zinc isotope fractionation in the hyperaccumulator Noccaea caerulescens and the nonaccumulating plant Thlaspi arvense at low and high Zn supply[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(15): 8020-8027.

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Wiggenhauser M, Bigalke M, Imseng M, et al. Cadmium isotope fractionation in soil-wheat systems[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2016, 50(17): 9223-9231.

(  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Imseng M, Wiggenhauser M, Keller A, et al. Towards an understanding of the Cd isotope fractionation during transfer from the soil to the cereal grain[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2019, 244: 834-844. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.09.149

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Wasylenki L E, Swihart J W, Romaniello S J. Cadmium isotope fractionation during adsorption to Mn oxyhydroxide at low and high ionic strength[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2014, 140: 212-226. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2014.05.007

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Horner T J, Rickaby R E M, Henderson G M. Isotopic fractionation of cadmium into calcite[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2011, 312(1/2): 243-253.

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Guinoiseau D, Galer S J G, Abouchami W. Effect of cadmium sulphide precipitation on the partitioning of Cd isotopes: Implications for the oceanic Cd cycle[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2018, 498: 300-308. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2018.06.039

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Wei R F, Guo Q J, Tian L Y, et al. Characteristics of cadmium accumulation and isotope fractionation in higher plants[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 174: 1-11. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.02.003

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Wei R F, Guo Q J, Wen H J, et al. Fractionation of stable cadmium isotopes in the cadmium tolerant Ricinus communis and hyperaccumulator Solanum nigrum[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 24309. DOI:10.1038/srep24309

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Wei R F, Guo Q J, Yu G R, et al. Stable isotope fractionation during uptake and translocation of cadmium by tolerant Ricinus communis and hyperaccumulator Solanum nigrum as influenced by EDTA[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 236: 634-644. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.103

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Degryse F, Shahbazi A, Verheyen L, et al. Diffusion limitations in root uptake of cadmium and zinc, but not nickel, and resulting bias in the Michaelis constant[J]. Plant Physiology, 2012, 160(2): 1097-1109. DOI:10.1104/pp.112.202200

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Yan J L, Wang P T, Wang P, et al. A loss-of-function allele of OsHMA3 associated with high cadmium accumulation in shoots and grain of Japonicarice cultivars[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2016, 39(9): 1941-1954.

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Wiggenhauser M, Bigalke M, Imseng M, et al. Zinc isotope fractionation during grain filling of wheat and a comparison of zinc and cadmium isotope ratios in identical soil-plant systems[J]. New Phytologist, 2018, 219(1): 195-205. DOI:10.1111/nph.15146

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Wombacher F, Rehkämper M, Mezger K, et al. Stable isotope compositions of cadmium in geological materials and meteorites determined by multiple-collector ICPMS[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2003, 67(23): 4639-4654. DOI:10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00389-2

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Imseng M, Wiggenhauser M, Keller A, et al. Fate of Cd in agricultural soils: A stable isotope approach to anthropogenic impact, soil formation, and soil-plant cycling[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(4): 1919-1928.

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Wiggenhauser M, Bigalke M, Imseng M, et al. Using isotopes to trace freshly applied cadmium through mineral phosphorus fertilization in soil-fertilizer-plant systems[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 648: 779-786. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.127

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Liu M S, Zhang Q, Zhang Y N, et al. High-precision Cd isotope measurements of soil and rock reference materials by MC-ICP-MS with double spike correction[J]. Geostandards and Geoanalytical Research, 2020, 44(1): 169-182. DOI:10.1111/ggr.12291

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Yang S C, Lee D C, Ho T Y. The isotopic composition of Cadmium in the water column of the South China Sea[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2012, 98: 66-77. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2012.09.022

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Schmitt A D, Galer S J G, Abouchami W. High-precision cadmium stable isotope measurements by double spike thermal ionisation mass spectrometry[J]. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry, 2009, 24(8): 1079-1088. DOI:10.1039/b821576f

(  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Shiel A E, Barling J, Orians K J, et al. Matrix effects on the multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometric analysis of high-precision cadmium and zinc isotope ratios[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2009, 633(1): 29-37. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2008.11.026

(  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Abouchami W, Galer S J G, de Baar H J W, et al. Biogeochemical cycling of cadmium isotopes in the Southern Ocean along the Zero Meridian[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2014, 127: 348-367. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2013.10.022

(  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Yang W J, Ding K B, Zhang P, et al. Cadmium stable isotope variation in a mountain area impacted by acid mine drainage[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2019, 646: 696-703. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.210

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Wei R F, Guo Q J, Yang J X, et al. Application and progress of Cd isotope technology in environmental science (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 2014, 33(2): 525-536. [魏荣菲, 郭庆军, 杨俊兴, 等. 镉同位素技术在环境科学研究中的应用进展[J]. 生态学杂志, 2014, 33(2): 525-536.]

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Gao B, Liu Y, Sun K, et al. Precise determination of cadmium and lead isotopic compositions in river sediments[J]. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2008, 612(1): 114-120. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2008.02.020

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Wiederhold J G, Cramer C J, Daniel K, et al. Equilibrium mercury isotope fractionation between Dissolved Hg(Ⅱ) species and thiol-bound Hg[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(11): 4191-4197.

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Fulda B, Voegelin A, Kretzschmar R. Redox-controlled changes in cadmium solubility and solid-phase speciation in a paddy soil as affected by reducible sulfate and copper[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(22): 12775-12783.

(  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Parsons J G, Dokken K M, McClure J, et al. FTIR, XAS, and XRD study of cadmium complexes with L-cysteine[J]. Polyhedron, 2013, 56: 237-242. DOI:10.1016/j.poly.2013.04.001

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Horner T J, Lee R B Y, Henderson G M, et al. Nonspecific uptake and homeostasis drive the oceanic cadmium cycle[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(7): 2500-2505. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1213857110

(  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Yang J L, Li Y B, Liu S Q, et al. Theoretical calculations of Cd isotope fractionation in hydrothermal fluids[J]. Chemical Geology, 2015, 391: 74-82. DOI:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2014.10.029

(  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Zhu C W, Wen H J, Zhang Y X, et al. Cd isotope fractionation during sulfide mineral weathering in the Fule Zn-Pb-Cd deposit, Yunnan Province, Southwest China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 616: 64-72.

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Zhang Y X, Wen H J, Zhu C W, et al. Cd isotope fractionation during simulated and natural weathering[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 216: 9-17. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.04.060

(  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Khaokaew S, Chaney R L, Landrot G, et al. Speciation and release kinetics of cadmium in an alkaline paddy soil under various flooding periods and draining conditions[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(10): 4249-4255.

(  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Khaokaew S, Chaney R L, Landrot G, et al. Speciation and release kinetics of cadmium in an alkaline paddy soil under various flooding periods and draining conditions[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(10): 4249-4255.

(  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Li H, Luo N, Li Y W, et al. Cadmium in rice: Transport mechanisms, influencing factors, and minimizing measures[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 224: 622-630. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.01.087

(  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Fujii T, Moynier F, Pons M L, et al. The origin of Zn isotope fractionation in sulfides[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2011, 75(23): 7632-7643. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2011.09.036

(  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Xie R C, Rehkämper M, Grasse P, et al. Isotopic evidence for complex biogeochemical cycling of Cd in the eastern tropical South Pacific[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2019, 512: 134-146. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2019.02.001

(  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Aomi S, Makino T. Functional effects of manganese and iron oxides on the dynamics of trace elements in soils with a special focus on arsenic and cadmium: A review[J]. Geoderma, 2016, 270: 68-75. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.12.017

(  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Wang J, Wang P M, Gu Y, et al. Iron-manganese(oxyhydro) oxides, rather than oxidation of sulfides, determine mobilization of Cd during soil drainage in paddy soil systems[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(5): 2500-2508.

(  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Muehe E M, Adaktylou I J, Obst M, et al. Organic carbon and reducing conditions lead to cadmium immobilization by secondary Fe mineral formation in a pH-neutral soil[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(23): 13430-13439.

(  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Nelson J, Wasylenki L, Bargar J R, et al. Effects of surface structural disorder and surface coverage on isotopic fractionation during Zn(Ⅱ) adsorption onto quartz and amorphous silica surfaces[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2017, 215: 354-376. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2017.08.003

(  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Welikala D, Hucker C, Hartland A, et al. Trace metal mobilization by organic soil amendments: Insights gained from analyses of solid and solution phase complexation of cadmium, nickel and zinc[J]. Chemosphere, 2018, 199: 684-693. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.02.069

(  0) 0) |

| [52] |

Khan M A, Khan S, Khan A, et al. Soil contamination with cadmium, consequences and remediation using organic amendments[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2017, 601/602: 1591-1605. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.030

(  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Karlsson T, Elgh-Dalgren K, Björn E, et al. Complexation of cadmium to sulfur and oxygen functional groups in an organic soil[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2007, 71(3): 604-614. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2006.10.011

(  0) 0) |

| [54] |

Kiczka M, Wiederhold J G, Kraemer S M, et al. Iron isotope fractionation during Fe uptake and translocation in alpine plants[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(16): 6144-6150.

(  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Deng T H, Cloquet C, Tang Y T, et al. Nickel and zinc isotope fractionation in hyperaccumulating and nonaccumulating plants[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(20): 11926-11933.

(  0) 0) |

| [56] |

Ryan B M, Kirby J K, Degryse F, et al. Copper isotope fractionation during equilibration with natural and synthetic ligands[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(15): 8620-8626.

(  0) 0) |

| [57] |

Wei R F, Guo Q J, Wen H J, et al. An analytical method for precise determination of the cadmium isotopic composition in plant samples using multiple collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry[J]. Analytical Methods, 2015, 7(6): 2479-2487. DOI:10.1039/C4AY02435D

(  0) 0) |

| [58] |

Rodushkin I, Stenberg A, Andrén H, et al. Isotopic fractionation during diffusion of transition metal ions in solution[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2004, 76(7): 2148-2151. DOI:10.1021/ac035296g

(  0) 0) |

| [59] |

Ishikawa S, Ishimaru Y, Igura M, et al. Ion-beam irradiation, gene identification, and marker-assisted breeding in the development of low-cadmium rice[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012, 109(47): 19166-19171. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1211132109

(  0) 0) |

| [60] |

Bozzi A T, Bane L B, Weihofen W A, et al. Conserved methionine dictates substrate preference in Nramp-family divalent metal transporters[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2016, 113(37): 10310-10315. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1607734113

(  0) 0) |

| [61] |

Moore R E T, Ullah I, de Oliveira V H, et al. Cadmium isotope fractionation reveals genetic variation in Cd uptake and translocation by Theobroma cacao and role of natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 5 and heavy metal ATPase-family transporters[J]. Horticulture Research, 2020, 7: 71. DOI:10.1038/s41438-020-0292-6

(  0) 0) |

| [62] |

Uraguchi S, Mori S, Kuramata M, et al. Root-to-shoot Cd translocation via the xylem is the major process determining shoot and grain cadmium accumulation in rice[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2009, 60(9): 2677-2688. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erp119

(  0) 0) |

| [63] |

Clemens S, Ma J F. Toxic heavy metal and metalloid accumulation in crop plants and foods[J]. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2016, 67(1): 489-512. DOI:10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-112301

(  0) 0) |

| [64] |

Li Q, Guo J Y, Zhang X Z, et al. Changes of non-protein thiols in root and organic acids in xylem Sap involved in cadmium translocation of cadmium-safe rice line(Oryza Sative L.)[J]. Plant and Soil, 2019, 439(1/2): 475-486. DOI:10.1007/s11104-019-04051-8?utm_content=null

(  0) 0) |

| [65] |

Clemens S. Metal ligands in micronutrient acquisition and homeostasis[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2019, 42(10): 2902-2912.

(  0) 0) |

| [66] |

Saathoff A J, Ahner B, Spanswick R M, et al. Detection of phytochelatin in the xylem sap of Brassica napus[J]. Environmental Engineering Science, 2011, 28(2): 103-111. DOI:10.1089/ees.2010.0183

(  0) 0) |

| [67] |

Mou R X, Cao Z Y, Lin X Y, et al. Characterization of the phytochelatins and their derivatives in rice exposed to cadmium based on high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with data-dependent hybrid linear ion trap orbitrap mass spectrometry[J]. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 2016, 30(16): 1891-1900.

(  0) 0) |

| [68] |

Nocito F F, Lancilli C, Dendena B, et al. Cadmium retention in rice roots is influenced by cadmium availability, chelation and translocation[J]. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2011, 34(6): 994-1008.

(  0) 0) |

| [69] |

Clemens S, Aarts M G M, Thomine S, et al. Plant science: The key to preventing slow cadmium poisoning[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2013, 18(2): 92-99. DOI:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.003

(  0) 0) |

| [70] |

Isaure M P, Huguet S, Meyer C L, et al. Evidence of various mechanisms of Cd sequestration in the hyperaccumulator Arabidopsis halleri, the non-accumulator Arabidopsis lyrata, and their progenies by combined synchrotron-based techniques[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2015, 66(11): 3201-3214. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erv131

(  0) 0) |

| [71] |

Peng J S, Wang Y J, Ding G, et al. A pivotal role of cell wall in cadmium accumulation in the Crassulaceae hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola[J]. Molecular Plant, 2017, 10(5): 771-774. DOI:10.1016/j.molp.2016.12.007

(  0) 0) |

| [72] |

Cheng M M, Wang P, Kopittke P M, et al. Cadmium accumulation is enhanced by ammonium compared to nitrate in two hyperaccumulators, without affecting speciation[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2016, 67(17): 5041-5050. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erw270

(  0) 0) |

| [73] |

Yamaji N, Ma J F. The node, a hub for mineral nutrient distribution in graminaceous plants[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2014, 19(9): 556-563. DOI:10.1016/j.tplants.2014.05.007

(  0) 0) |

| [74] |

Kato M, Ishikawa S, Inagaki K, et al. Possible chemical forms of cadmium and varietal differences in cadmium concentrations in the phloem Sap of rice plants(Oryza sativa L.)[J]. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 2010, 56(6): 839-847. DOI:10.1111/j.1747-0765.2010.00514.x

(  0) 0) |

| [75] |

Yu S S, Bian Y F, Zhou R, et al. Robust method for the analysis of phytochelatins in rice by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray tandem mass spectrometry based on polymeric column materials[J]. Journal of Separation Science, 2015, 38(23): 4146-4152. DOI:10.1002/jssc.201500557

(  0) 0) |

| [76] |

Mendoza-Cózatl D G, Butko E, Springer F, et al. Identification of high levels of phytochelatins, glutathione and cadmium in the phloem sap of Brassica napus. A role for thiol-peptides in the long-distance transport of cadmium and the effect of cadmium on iron translocation[J]. The Plant Journal, 2008, 54(2): 249-259. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03410.x

(  0) 0) |

| [77] |

Zhang C H, Yin X M, Gao K H, et al. Non-protein thiols and glutathione S-transferase alleviate Cd stress and reduce root-to-shoot translocation of Cd in rice[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 2013, 176(4): 626-633. DOI:10.1002/jpln.201100276

(  0) 0) |

2021, Vol. 58

2021, Vol. 58