氢气(Hydrogen,H2)具有分子量小、密度小、可燃性高、良好的还原性和导热性等特点,常作为一种高能量密度的零碳燃料被广泛应用于新能源、航天、化工、电子、轻工业等领域。近年来,随着H2应用的相关研究在生物学领域的开展,微生物H2代谢过程逐渐引起了科学界的广泛关注。最近在Nature及Nature Microbiology等期刊的研究表明,H2在大气痕量水平或高浓度水平下能被微生物利用,同时在有氧或无氧呼吸利用H2时能产生较高的能量,而且利用H2所需的细胞资源最小[1-4]。由此可见,H2也是一种高度可靠的微生物生存所需的能量来源。H2的主要来源是生物地球化学过程和人类活动,而土壤生态系统是主要H2汇,土壤中的H2氧化微生物进化出高亲合力氢化酶,每年合计消耗大气损失H2总量的75%(60 Tg),使得全球大气中H2平均浓度维持在痕量水平(约0.53×10–6(v︰v))[5-6]。环境中诸多微生物过程依赖于H2的产生和消耗,因此,H2作为微生物生存的重要能源对其他重要元素生物地球化学循环具有潜在的驱动作用[7-8]。

产氢微生物和耗氢微生物的发现是近代微生物学的一大重要进展。产氢微生物会在缺氧或好氧条件下通过不同途径产生H2,而这种可扩散气体作为多种微生物代谢之间相互作用的关键中介物,可为耗氢微生物提供维持其活力与活性的能源[4,8-9]。在生态系统水平上,产氢和耗氢微生物对环境中微生物群落的稳定性和功能起着至关重要的作用,比如热液喷口和缺氧沉积物中的固碳微生物以及有机卤化物污染的地下水和土壤环境中的光合微生物和还原脱卤微生物[6-9]。目前,H2代谢相关的热点研究主要围绕环境中微生物氢化酶的多样性、结构、分类、进化关系与功能等方面,其中氢化酶在生物产氢和生物修复方面的作用是关注的焦点[6,8]。已有研究表明,H2可被厌氧脱卤微生物用作还原脱卤的电子供体,其中氢化酶在脱卤过程中起到协助作用[10–12]。此外,微生物氢化酶已用于修复含金属的工业废物,以减少潜在的有毒金属[13]。在氢化酶的影响下,微生物代谢活动可影响地下矿物和有机质的循环,并在有机和无机污染物的生物修复过程中发挥积极作用[8,14–15]。因此,利用氢化酶催化的H2代谢过程修复污染环境可能是一种很有前景的修复策略。本文系统总结和综合评述国内外微生物产生和消耗H2的多种途径及其对生态环境效应和生物修复作用影响的研究现状与进展,旨在为H2这种生物能源应用于生物修复提供重要科学依据。

1 氢气代谢及氢化酶分类和功能生物H2代谢过程是指生物产氢和耗氢的过程,主要由氢化酶催化;许多微生物具有表达多种不同生理作用氢化酶的基因组能力,因此增加了其在环境中的代谢灵活性[16]。

根据氢化酶活性位点和氨基酸序列之间的差异,将其分为[Fe]-氢化酶、[FeFe]-氢化酶和[NiFe]-氢化酶三大类。[Fe]-氢化酶是由两个38 kDa亚单位组成的同型二聚体,其催化中心仅有一个铁原子,并且不含Fe-S簇[8];这类[Fe]-氢化酶主要存在于一些产甲烷古菌(如Methanothermobacter marburgensis等)中,其催化氢气异裂产生负氢离子转移至底物次甲基四氢甲基喋呤(CH-H4MPT+)生成亚甲基四氢甲烷喋呤(methylene-H4MPT),并将CO2还原为甲烷[17]。[FeFe]-氢化酶是含有两个Fe原子活性中心(称为H-簇或Fe-S簇)的单聚、二聚、三聚或四聚酶[8]。[FeFe]-氢化酶主要作用是在严格厌氧条件下催化产H2,这类氢化酶主要存在于一些厌氧的厚壁菌、硫酸盐还原菌以及单细胞绿藻莱茵衣藻(Chlamydomonas reinhardtii)中[8,18–19]。[NiFe]-氢化酶是分布最广泛的氢化酶类,这类酶至少包含一个核心异二聚体成分,该成分由一个大的α-亚基(60 kDa)和一个小的β亚单位(30 kDa)组成[8]。[NiFe]-氢化酶代表一个异构的氢化酶组,根据其系统发育分为5个亚组[5]:1组、2组、3组、4组和5组[NiFe]-氢化酶;这5个亚组的[NiFe]-氢化酶的分类、功能、常见基因名及代表物种的总结见表 1。

|

|

表 1 [NiFe]-氢化酶的分类、功能、常见基因名及代表物种 Table 1 Classification, function, common used gene names and representative species of [NiFe]- hydrogenase |

尽管取得以上一系列研究进展,但有关氢化酶的结构和催化机理方面的相关研究仍需进一步探索。迄今为止,仍未成功分离纯化出能够氧化痕量H2浓度的高亲和力氢化酶[3]。此外,有必要区分高亲和力和低亲和力氢化酶在组成和分子结构方面的差异,以更清晰的视角了解氢化酶释放的电子如何用于有氧呼吸和固碳过程。

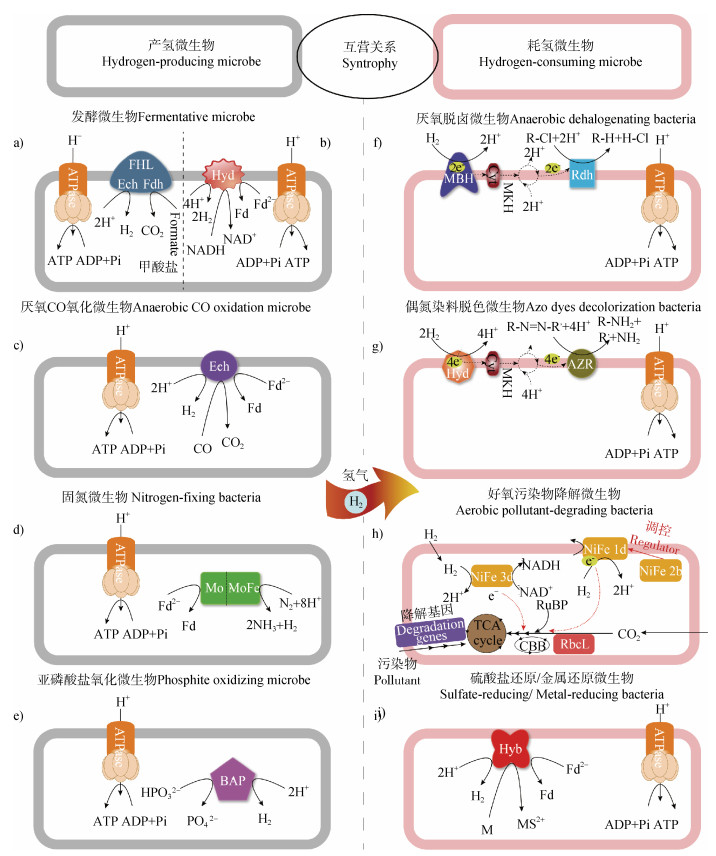

2 微生物产氢过程及其生态环境效应在厌氧或有氧生态系统中的微生物能通过氢化酶催化H2的产生。目前,微生物产生H2的过程主要包括:厌氧发酵产氢、厌氧一氧化碳(CO)氧化产氢、固氮过程以及亚磷酸盐氧化过程产氢(图 1)。这些H2会以痕量浓度在大气中存在或者在局部区域以高浓度存在,形成H2热点,从而对局部生态环境产生一定的影响。

|

图 1 产氢微生物与耗氢微生物在污染物降解中的互营作用 Fig. 1 Syntrophic interactions between hydrogen-producing and hydrogen-consuming microbes in pollutant degradation |

厌氧发酵产氢微生物在厌氧条件下利用富含碳水化合物的底物通过持续还原质子产生H2(图 1a,图 1b)。比如,梭菌属(Clostridium spp.)、瘤胃菌群(Rumen flora)、肠杆菌属(Enterobacter spp.)等发酵微生物在[FeFe]-氢化酶的作用下,可通过不同的丙酮酸代谢途径有效地产生H2(图 1a)[5,7-8]。此外,铁氧还蛋白依赖的[NiFe]-氢化酶和还原型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸(NADH)依赖的[Fe]-氢化酶可催化嗜热菌(Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis)中NADH的再氧化从而产生H2(图 1b)[26]。

厌氧CO氧化产氢微生物在黑暗条件下厌氧生长,能够以CO作为电子供体,把水中的H+还原为H2,同时氧化CO为CO2(图 1c)。Uffen[27]发现,深红红螺菌(Rhodospirillum rubrum)可在CO不敏感[NiFe]-氢化酶和CO脱氢酶组成的复合酶催化作用下氧化CO并还原质子产生H2。最近,Kochetkova等[28]首次分离出在严格厌氧条件下可使用CO作为能量源产生H2的丝状古菌菌株(Thermofilum sp. strain 1505),并在其基因组上发现了一个包含厌氧CO脱氢酶基因和能量转换氢化酶基因的基因簇。

在生物固氮过程中,H2是固氮酶与N2反应的一种专性副产物(图 1d),其产生H2的能量约占流经固氮酶能量流的30%~50%[6]。在部分固氮微生物中含有氧化H2的吸氢酶,不仅有利于持续的N2固定,也可能作为固氮酶和其他代谢过程的额外电子源[29]。许多根瘤菌能在豆科植物根瘤中共生固定N2,同时产生H2,其中研究较多的共生固氮微生物主要包括慢生型大豆根瘤菌(Bradyrhizobium japonicum)、苜蓿中华根瘤菌(Sinorhizobium meliloti)和豌豆根瘤菌(Rhizobium leguminosarum)等[30]。一些自生固氮菌和蓝藻也能通过固氮过程产生H2,比如棕色固氮菌(Azotobacter vinelandii)、鱼腥蓝细菌(Anabaena cylindrica)和藓类念珠藻(Nostoc muscorum)等[31]。此外,厚壁菌门的一些梭菌属(Clostridium spp.)和芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus spp.)以及产甲烷古菌也能在微氧或者厌氧条件下固定N2产生H2[5]。值得注意的是,光营养细菌也可通过固氮酶催化质子还原的光合反应释放大量H2,这类微生物主要包括:深红红螺菌(Rhodospirillum rubrum)、荚膜红杆菌(Rhodobater capsulatus)、桃红荚硫菌(Thiocapsa roseopersicina)和嗜盐菌(Halobacterium halobium)等[32]。

亚磷酸盐氧化过程产氢主要是通过来自亚磷酸盐的氢负离子(H–)作为离去基团与质子反应形成H2(图 1e)。亚磷酸盐氧化过程产氢目前仅在大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)中发现,其主要是由phoA基因编码的周质蛋白-细菌碱性磷酸酶(Bacterial Alkaline Phosphata,BAP)催化完成的;迄今为止,该酶是唯一显示具有产氢活性的微生物磷酸酶[33]。

2.2 产氢过程的生态环境效应痕量H2在维持生态系统中微生物生存和生长以及元素生物地球化学循环等方面发挥了重要作用。H2产生于江河湖海的底泥、土壤、沼泽、枯叶、粪便、污水污泥等自然环境,通常在含水层中H2的含量在20~100 nmol·L–1之间,而在土壤或者底泥等生境中有机物发酵时产生的H2浓度很少超过10 nmol·L–1[34]。然而,几乎所有产生的H2均会被土壤中H2氧化微生物吸收利用,不会被释放至大气中。最近的研究表明,H2氧化微生物是土壤微生物群落中广泛存在和活跃的成员,这对H2代谢仅限于高H2和低O2环境的传统观点提出了挑战[2,7,35]。由于H2气体具有通过细胞膜扩散和低活化能的特点,微生物仅需消耗很少的资源来吸收这些来源于大气和土壤中且广泛存在于所有土壤中的H2气体,并且可利用H2氧化过程释放的大量自由能来合成腺嘌呤核苷三磷酸(ATP)和固定CO2[1]。已有的全基因组和宏基因组调查研究表明,至少有17个不同门的土壤微生物可编码以消耗H2作为能源的[NiFe]-氢化酶[1,7,15]。H2氧化微生物通过氧化H2作为普遍的生长和维持生存能源的活动,为促进生物地球化学循环提供重要的服务功能[5]。除了微生物过程产生H2外,大气H2主要来源于人为活动以及大气甲烷(CH4)和非甲烷碳氢化合物的氧化。这些H2也会参与H2O、温室气体以及各种污染物的大气化学循环过程[36]。可见,痕量H2氧化的功能是高度多样化的,一方面能满足长期生存以及生长过程所需的能量,另一方面也可进行碳固定;然而,在生态系统层面上,这些高度多样化的痕量H2氧化功能可能对生态系统功能的发挥至关重要。

高浓度H2通过影响局部区域环境中微生物群落组成从而影响物质循环过程。已有研究表明,豆科植物-根瘤菌共生体系或自由生活的固氮微生物在固氮过程中会产生大量的H2作为副产品[37]。据估计,固氮豆科植物根瘤内的H2浓度范围为9 000~27 000×10–6(v:v),其在植物生长季节的扩散损失可能达到240 000 L[30]。然而,这些H2能否被释放至土壤中主要是由共生的根瘤菌中是否含有吸收H2的[NiFe]-氢化酶所决定[38]。在含有H2氧化吸氢酶(Hup+型)的豆科植物根际,H2的能量可通过[NiFe]-氢化酶回收,而在不含H2氧化吸氢酶(Hup–型)豆科植物根际的H2则会被释放至周围土壤中。有趣的是,Wang等[39]最近的研究发现,紫花苜蓿(Medicago sativa L.)接种根瘤菌(Sinorhizobium meliloti strain NM)后能通过固氮过程产生H2,在根瘤内为四氯联苯的脱氯提供一个还原环境,但这种生物H2对污染物转化有何影响尚需进一步探究。越来越多的证据表明,从根瘤释放至周围土壤中的H2通过富集土壤中好氧H2氧化细菌或植物根际促生细菌,从而在增加植物生物量方面起着关键作用[30,40]。多种H2氧化微生物可水解溶解性有机物,也可参与颗粒有机物的分解,包括纤维素、半纤维素、木质素、腐殖物质和多环芳香族化合物[41],还可催化CO、CO2和CH4的氧化还原。H2氧化微生物能够在不同的营养模式之间进行转换,包括碳源和能量来源,这使它们在接受各种碳输入时具有强大的代谢多样性[5]。此外,在富含H2的微域环境中,例如豆科植物根际和白蚁肠道等,H2氧化微生物释放的代谢物也可能导致土壤有机物的分解和转化[42]。最近的研究结果表明,在自然生态系统中发现的不同H2混合比例能导致土壤微生物群落结构的变化和群落功能的协调反馈,并揭示H2氧化微生物通过环境相关H2浓度与土壤中H2、CH4和CO的生物汇之间的剂量-反应关系,支持H2为微生物提供各种生态系统服务的代谢和能量灵活性[42-43]。因此,可以预期H2氧化微生物执行的其他碳循环过程,如分解、腐殖化和水解,也会在富含H2的生态系统中增加[5]。尽管目前研究已揭示局部区域的高浓度H2可通过影响H2氧化微生物对植物起到促生作用,影响土壤碳循环等过程,但未来研究亦需针对H2如何调控植物与微生物之间的交互作用等方面开展,从而为发展氢农业提供重要的科学依据。

3 耗氢微生物的环境修复功能环境H2代谢微生物除了在维持环境生态系统平衡中发挥重要作用外,在消除次生环境污染等过程中也扮演着不容忽视的重要作用。生物和非生物产生的H2可被释放并用于支持氢营养原核生物的生长和代谢[3,5]。目前认为,许多微生物类群可利用H2作为电子供体,催化有机卤化物、偶氮化合物和潜在有毒元素等污染物的还原过程[44]。

3.1 有机污染物降解目前已从受污染的土壤、淤泥、沉积物、含水层、淡水和海洋栖息地中分离出多种有机卤化物呼吸的微生物[45],它们在厌氧条件下利用H2作为电子供体对卤化有机物进行脱卤(图 1f),比如脱硫菌属(Desulfomonile)、脱卤球菌属(Dehalococcoides)、脱卤杆菌属(Dehalobacter)、脱硫杆菌属(Desulfitobacterium)、脱硫单胞菌属(Desulfuromonas)和硫螺菌属(Sulfurospirillum)等[46-48]。上述有机卤化物呼吸微生物将还原脱卤和能量代谢(ATP合成)耦合在一起,利用还原性脱卤酶(RDase)将氢原子取代卤素取代基,从而降解顽固性有机污染物并降低其毒性;其中膜结合氢化酶是吸收分子H2释放电子的初始氧化剂,参与H2作为电子供体的电子转移过程,在有机卤化物呼吸过程中发挥至关重要的作用[44,46,49]。有机卤化物呼吸的微生物中常见氢化酶总结见表 2。最近,Schubert等[50]和Türkowsky等[51]在Dehalococcoides mccartyi CBDB1中鉴定出一种独特的结合了吸氢酶、复合铁硫钼酶和还原性脱卤酶的多酶呼吸复合物;尽管其结构已经被解析但涉及其中的电子传递路径与化学渗透进行耦合的机制仍不明晰,这对这些“神秘”微生物的能量守恒模式提出了新的科学问题。因此,有机卤化物呼吸细菌在脱卤过程中介导电子传递的各种膜相关氢化酶以及呼吸复合物的电子转移与质子易位的耦合位点值得进一步探讨[44,50]。在未来的研究中,了解不同的有机卤化物呼吸微生物中氢化酶基因的编码及多样性有助于阐明H2代谢的动力学特征,优化有机卤化物呼吸微生物的生长,并在不同H2浓度可能刺激或抑制有机卤化物呼吸微生物生长的污染环境中调节其脱卤速率,以达到强化生物修复的目的。

|

|

表 2 有机卤化物呼吸微生物中常见氢化酶总结 Table 2 Summary of common hydrogenase in organohalide-respiring bacteria |

在厌氧条件下,一些微生物能够利用偶氮化合物作为碳源,通过氢化酶氧化H2维持其生长,从而达到偶氮还原及脱色的目的,比如脱色希瓦氏菌(Shewanella decolorationis)和硫酸盐还原微生物等[58]。偶氮化合物的细胞外还原主要是由多组分电子转移链参与,细胞质/外膜、周质、c型细胞色素和甲醌等,Hya型[NiFe]-氢化酶或Hyd型[Fe]-氢化酶作为介导H2氧化的关键枢纽,为氮还原代谢提供电子,将H2的氧化与偶氮化合物的还原结合起来,以维持微生物生长(图 1g)[58-59]。Watrous等[60]研究表明,在严格厌氧菌乙酰肉毒梭菌(Clostridium acetobotulinicum)中,[Fe]-氢化酶负责在产酸环境中将2,4,6-三硝基甲苯(2,4,6-trinitrotoluene,TNT)的硝基取代基还原为相应的羟胺。据报道,奥奈达希瓦氏菌(Shewanella oneidensis MR-1)中的周质HyaB型[NiFe]氢化酶和周质HyaA型[FeFe]氢化酶作为吸氢酶能参与多种偶氮染料的脱色过程[61]。

尽管目前H2氧化微生物的环境修复潜能已逐渐受到重视,但目前开展的研究主要集中于厌氧条件下探讨不同微生物如何利用H2作为电子供体催化还原有机卤化物和偶氮化合物等污染物[44],而有关好氧H2氧化微生物通过H2氧化过程对污染物降解的影响机制关注较少。最近,Xu等[15,62]在好氧高浓度H2(约50 000×10–6(v︰v))条件下系统研究了外源H2对两种不同土壤类型中四氯联苯PCB77降解的影响发现,外源H2对不同类型土壤中PCB77消减的影响不同;其作用的机制主要为:H2能显著刺激具有PCB降解功能的H2氧化微生物的富集,从而促进PCB污染土壤的生物修复(图 1h)。其中的宏基因分析结果表明,1d组、2b组和3d组的[NiFe]-氢化酶在降解过程中发挥了关键的协助作用[15](图 1h)。此外,最近有研究表明,应用外源和内源H2均可通过刺激油菜素甾醇来增强杀菌剂百菌清在植物中的降解[63],但在该条件下,植物根际H2氧化微生物对土壤中杀菌剂降解的影响仍不明晰。尽管取得以上研究进展,但在好氧条件下H2氧化微生物对其他有机污染物的降解效应及其机制以及如何影响受污染土壤的群落结构和生物地球化学循环(如碳、氮、磷和硫代谢过程),目前尚不清楚,值得进一步深入探究。

3.2 潜在毒性元素的还原硫酸盐还原菌(Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria,SRB)或金属还原菌(Metal-Reducing Bacteria)通过利用H2或其他有机化合物作为末端电子供体还原潜在毒性元素来实现其修复功能(图 1i)。Tebo和Obraztsova[64]从潜在毒性元素污染沉积物中分离出第一株硫酸盐还原菌Desufotomaculum reducens sp.nov. MI-1,该菌株可利用H2作为电子供体,金属(如Cr(VI)、Mn(IV)、Fe(III)和U(VI))作为末端电子受体,将H2氧化偶联催化金属还原来进行生长。迄今为止,已鉴定出40多种硫酸盐还原菌,主要包括脱硫菌属(Desulfobacter)、脱硫弧菌属(Desulfovibrio)、脱硫弯杆菌属(Desulfotomaculum)和脱硫微菌属(Desulfomicrobium)等[13,65]。Deplanche等[66]研究表明,Hyd型[NiFe]-氢化酶参与利用大肠杆菌(Escherichia coli)生物还原Pd(II)形成高催化Pd(0)纳米颗粒。对金属还原菌(Shewanella oneidensis)的基因组序列进行了全面分析,发现[Fe]-氢化酶和细胞色素参与电子传递和金属还原过程[67]。此外,Zadvorny等[68]从光合细菌桃红荚硫菌(Thiocapsa roseopersicina)和嗜中盐闪杆菌(Lamprobacter modestohalophilus)中分离纯化的氢化酶在H2气氛下能将Ni(II)、Pt(IV)、Pd(II)或Ru(III)还原为金属。由此可见,氢化酶可作为一种新型的参与金属氧化还原过程的酶,在潜在毒性元素的生物修复中具有重要的理论意义和潜在的应用前景。

4 氢气代谢微生物互营耦合污染物降解产氢微生物与耗氢微生物之间可通过直接方式或间接方式传递电子形成互营生长关系;这种发生种间分子氢转移的过程能够为微生物物种提供多样性代谢以适应复杂的生态环境。在复杂的环境中,产氢微生物和耗氢微生物之间的互营关系对于污染物降解和全球碳循环至关重要[55,69]。Odom和Peck[70]首次记录了硫酸盐还原菌在硫酸盐限制条件下,其通过底物发酵产生的多余H2转移至其他耗氢细菌的过程。随后,Stams和Plugge[71]发现了产甲烷菌和古细菌互营过程中的种间H2转移还涉及长链脂肪酸转化过程。Lee等[72]在复杂的微生物群落中发现,在互营的微生物维持较低的H2分压时,三氯甲烷脱氯过程中存在物种间H2转移。Men等[73]研究发现,产乙烯脱卤拟球菌(Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195)可与普通脱硫弧菌(Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough)和氢营养甲烷菌(Methanobacterium congolense)互营生长;与单培养产乙烯脱卤拟球菌(Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195)降解三氯乙烯体系相比,其互营体系中的三氯乙烯的脱氯活性提高了3倍。这也表明,互营体系中微生物的相互作用可更有效地转移H2,有助于微生物更快速地生长和污染物更快地降解。

图 1总结了污染物降解过程中产氢微生物和耗氢微生物之间可能存在的互营相互作用过程。产氢微生物和耗氢微生物通过感知细胞内氧化还原条件,相互影响互营群落中的代谢过程[74]。基于对产氢和耗氢的能量平衡分析,产氢和有机卤化物降解之间的能量转换反应可能涉及同营养的产氢和耗氢微生物[74]。脱卤微生物(如Dehalococcoides sp. BAV1和Dehalococcoides ethenogenes 195)在分离培养时可利用乙酸作为碳源,H2作为电子供体,表现出有限的脱氯活性和较低的生长速率[74-75]。因此,可通过增强脱卤微生物的生长和脱氯活性来开发和改进污染物的生物修复策略[73]。然而,许多种间H2转移的相互作用是互营的,因此仅存在于复杂的微生物群落中,而不存在于纯培养物中。在复杂的微生物群落中,H2间接介导电子供体和受体之间的电子穿梭。氢营养菌可从其互营的产氢微生物产生的H2中获利,从而转化污染物。因此,产氢微生物和耗氢微生物对其自身的生长至关重要,也可能促进污染物的降解[44,72]。

5 展望分子H2通过大气、生物、地球化学和人为来源在大多数生态系统中以微量或局部“热点”的形式存在,是微生物生存的普遍可用性能源,对生物地球化学循环具有潜在的驱动作用。产氢微生物和耗氢微生物之间的互营作用可用于去除有毒化合物。然而,针对H2代谢过程及氢化酶在环境生物修复领域应用潜力的相关研究还十分不足。因此,建议今后重点在以下几个方面开展研究:

(1)揭示H2代谢菌与污染物降解菌互营的作用机制。微生物互营的核心是微生物种间的电子传递机制,而在自然环境中,很多微生物可利用H2作为电子供体还原污染物,从而降低污染物的毒性[74]。利用宏基因组测序、单基因荧光原位杂交、功能基因阵列、原位质谱技术、稳定性同位素核酸探针及纳米二次离子质谱等技术追踪参与H2代谢的污染物降解菌的动态,并解析污染物降解菌和H2代谢菌在降解过程中的相互作用及微生物间电子传递策略,拓宽对微生物电子传递方式多样性的认识,有助于设计利用微生物修复环境污染物的策略。

(2)阐明土壤条件对耗氢微生物降解污染物的影响机制。土壤是一个复杂的动态生命系统,从土壤到微生物,污染物的生物有效性涉及微生物吸附和解吸、运输和吸收的全过程,微生物也会受土壤条件的影响,如土壤有机质、土壤矿物、土壤水分、土壤温度和土壤团聚体等[76-77]。因此,土壤条件对耗氢微生物降解污染物的影响及其机制亟需进一步探索。

(3)解析生物修复过程中的氢化酶或其他协同酶的结构特征。质子ATP酶或其他膜结合二级转运体会影响氢化酶活性,从而影响H2代谢过程[78]。因此,参与环境生物修复过程的氢化酶或其他协同酶(如ATP酶和脱卤酶Rdase)的结构研究对于指导蛋白质工程至关重要。例如,通过识别与活性位点的蛋白质环境相关的因素,使这些酶具有活性,以提高污染物的降解效率。氢化酶和其他协同酶已被证明在污染物降解中起着重要作用,因此,对这些酶在环境生物修复过程中的基因组、转录组和蛋白组数据的分析可能会为氢化酶参与污染物降解的机制提供重要见解。

(4)研发用于生物修复的H2或产氢功能材料与技术。运用H2或产氢材料,在生物修复领域中探索并实践富氢水及其他相关应用方式具有重要的研究价值,值得进一步深入探讨。富氢水在缓解植物对潜在毒性元素毒害方面具有显著效果[79],但大规模田间试验以及相关的推广与示范工作尚未落实。氢气纳米气泡水作为一种新的生物体氢气输送技术[80],其应用对植物及土壤微生物的影响及其对污染物的生物修复作用仍然未知。此外,新型固态储氢材料作为氢能产业化发展的关键材料[81],其在生物修复领域中的应用尚未开展;值得注意的是,新型固态储氢材料作为生物修复材料的同时也应注意材料本身对生态环境的影响。

通过上述重点方向研究,有望揭示复杂环境中产氢微生物和耗氢微生物的互营关系及其耦合有毒化合物去除的作用机制,构建高效协助污染物降解的氢化酶及基于H2的高效修复材料,为未来提供一种低投入、生态友好的生物修复策略。

| [1] |

Ji M K, Greening C, Vanwonterghem I, et al. Atmospheric trace gases support primary production in Antarctic desert surface soil[J]. Nature, 2017, 552(7685): 400-403. DOI:10.1038/nature25014

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Bay S K, Dong X Y, Bradley J A, et al. Trace gas oxidizers are widespread and active members of soil microbial communities[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2021, 6(2): 246-256. DOI:10.1038/s41564-020-00811-w

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Greening C, Grinter R. Microbial oxidation of atmospheric trace gases[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2022, 20(9): 513-528. DOI:10.1038/s41579-022-00724-x

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Greening C, Islam Z F, Bay S K. Hydrogen is a major lifeline for aerobic bacteria[J]. Trends in Microbiology, 2022, 30(4): 330-337. DOI:10.1016/j.tim.2021.08.004

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Piché-Choquette S, Constant P. Molecular hydrogen, a neglected key driver of soil biogeochemical processes[J]. Applied Environmental Microbiology, 2019, 85(6): e02418-18.

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Greening C, Constant P, Hards K, et al. Atmospheric hydrogen scavenging; from enzymes to ecosystems[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2015, 81(4): 1190-1199. DOI:10.1128/AEM.03364-14

(  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Greening C, Biswas A, Carere C R, et al. Genomic and metagenomic surveys of hydrogenase distribution indicate H2 is a widely utilised energy source for microbial growth and survival[J]. The ISME Journal, 2016, 10(3): 761-777. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2015.153

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Vignais P M, Billoud B. Occurrence, classification, and biological function of hydrogenases; An overview[J]. Chemical Reviews, 2007, 107(10): 4206-4272. DOI:10.1021/cr050196r

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Marshall I P G, Berggren D R V, Azizian M F, et al. The hydrogenase chip; A tiling oligonucleotide DNA microarray technique for characterizing hydrogen-producing and-consuming microbes in microbial communities[J]. The ISME Journal, 2012, 6(4): 814-826. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2011.136

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Seshadri R, Adrian L, Fouts D E, et al. Genome sequence of the PCE-dechlorinating bacterium Dehalococcoides ethenogenes[J]. Science, 2005, 307(5706): 105-108. DOI:10.1126/science.1102226

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Rahm B G, Morris R M, Richardson R E. Temporal expression of respiratory genes in an enrichment culture containing Dehalococcoides ethenogenes[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(8): 5486-5491. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00855-06

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Kublik A, Deobald D, Hartwig S, et al. Identification of a multi‐protein reductive dehalogenase complex in Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain CBDB 1 suggests a protein‐dependent respiratory electron transport chain obviating quinone involvement[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 18(9): 3044-3056. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.13200

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Li X, Lan S, Zhu Z, et al. The bioenergetics mechanisms and applications of sulfate-reducing bacteria in remediation of pollutants in drainage; A review[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2018, 158: 162-170. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.04.025

(  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Lovley D R. The microbe electric; conversion of organic matter to electricity[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2008, 19(6): 564-571. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2008.10.005

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Xu Y, Teng Y, Dong X, et al. Genome-resolved metagenomics reveals how soil bacterial communities respond to elevated H2 availability[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2021, 163: 108464. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108464

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Berney M, Greening C, Hards K, et al. Three different [NiFe] hydrogenases confer metabolic flexibility in the obligate aerobe Mycobacterium smegmatis[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 16(1): 318-330. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.12320

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Huang G, Wagner T, Ermler U, et al. Methanogenesis involves direct hydride transfer from H2 to an organic substrate[J]. Nature Reviews Chemistry, 2020, 4(4): 213-221. DOI:10.1038/s41570-020-0167-2

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Li Q S, Wang R, Ma Z Y, et al. Dietary selection of metabolically distinct microorganisms drives hydrogen metabolism in ruminants[J]. The ISME Journal, 2022, 16(11): 2535-2546. DOI:10.1038/s41396-022-01294-9

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Engelbrecht V, Liedtke K, Rutz A, et al. One isoform for one task? The second hydrogenase of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii prefers hydrogen uptake[J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2021, 46(10): 7165-7175. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.11.231

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Pandelia M E, Lubitz W, Nitschke W. Evolution and diversification of Group 1 [NiFe] hydrogenases. Is there a phylogenetic marker for O2-tolerance?[J]. BBA-Bioenergetics, 2012, 1817(9): 1565-1575. DOI:10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.04.012

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Fan X, Zhang X, Zhao G, et al. Aerobic hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria in soil; From cells to ecosystems[J]. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio-Technology, 2022, 21: 1-28. DOI:10.1007/s11157-021-09607-8

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Ney B, Ahmed F H, Carere C R, et al. The methanogenic redox cofactor F420 is widely synthesized by aerobic soil bacteria[J]. The ISME Journal, 2017, 11(1): 125-137. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2016.100

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Thauer R K, Kaster A K, Goenrich M, et al. Hydrogenases from methanogenic archaea, nickel, a novel cofactor, and H2 storage[J]. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 2010, 79(1): 507-536. DOI:10.1146/annurev.biochem.030508.152103

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Schut G J, Nixon W J, Lipscomb G L, et al. Mutational analyses of the enzymes involved in the metabolism of hydrogen by the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2012, 3: 163.

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Constant P, Chowdhury S P, Hesse L, et al. Genome data mining and soil survey for the novel group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase to explore the diversity and ecological importance of presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(17): 6027-6035. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00673-11

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Losey N A, Poudel S, Boyd E S, et al. The beta subunit of non-bifurcating NADH-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenases differs from those of multimeric electron-bifurcating [FeFe]-hydrogenases[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2020, 11: 1109. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2020.01109

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Uffen R L. Anaerobic growth of a Rhodopseudomonas species in the dark with carbon monoxide as sole carbon and energy substrate[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1976, 73(9): 3298-3302.

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Kochetkova T V, Mardanov A V, Sokolova T G, et al. The first crenarchaeon capable of growth by anaerobic carbon monoxide oxidation coupled with H2 production[J]. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 2020, 43(2): 126064. DOI:10.1016/j.syapm.2020.126064

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Kosourov S, Leino H, Murukesan G, et al. Hydrogen photoproduction by immobilized N2-fixing cyanobacteria; understanding the role of uptake hydrogenase in the long-term process[J]. Applied Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(18): 5807-5817. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01776-14

(  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Dong Z, Wu L, Kettlewell B, et al. Hydrogen fertilization of soils–Is this a benefit of legumes in rotation?[J]. Plant Cell and Environment, 2003, 26(11): 1875-1879. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.01103.x

(  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Barney B M. Aerobic nitrogen-fixing bacteria for hydrogen and ammonium production; Current state and perspectives[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2020, 104(4): 1383-1399. DOI:10.1007/s00253-019-10210-9

(  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Das D, Veziroǧlu T N. Hydrogen production by biological processes; A survey of literature[J]. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2001, 26(1): 13-28. DOI:10.1016/S0360-3199(00)00058-6

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Yang K C, Metcalf W W. A new activity for an old enzyme; Escherichia coli bacterial alkaline phosphatase is a phosphite-dependent hydrogenase[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(21): 7919-7924.

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Nandi R, Sengupta S. Microbial production of hydrogen; An overview[J]. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 1998, 24(1): 61-84. DOI:10.1080/10408419891294181

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Bay S K, Waite D W, Dong X Y, et al. Chemosynthetic and photosynthetic bacteria contribute differentially to primary production across a steep desert aridity gradient[J]. The ISME Journal, 2021, 15(11): 3339-3356. DOI:10.1038/s41396-021-01001-0

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Tabak H H, Lens P, van Hullebusch E D, et al. Developments in bioremediation of soils and sediments polluted with metals and radionuclides-1. Microbial processes and mechanisms affecting bioremediation of metal contamination and influencing metal toxicity and transport[J]. Reviews in Environmental Science Bio-technology, 2005, 4(3): 115-156. DOI:10.1007/s11157-005-2169-4

(  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Mus F, Crook M B, Garcia K, et al. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and the challenges to its extension to nonlegumes[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(13): 3698-3710. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01055-16

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Annan H, Golding A L, Zhao, Y, et al. Choice of hydrogen uptake(Hup)status in legume-rhizobia symbioses[J]. Ecology and Evolution, 2012, 2(9): 2285-2290. DOI:10.1002/ece3.325

(  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Wang X M, Teng Y, Tu C, et al. Coupling between nitrogen fixation and tetrachlorobiphenyl dechlorination in a rhizobium–legume symbiosis[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(4): 2217-2224.

(  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Maimaiti J, Zhang Y, Yang J, et al. Isolation and characterization of hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria induced following exposure of soil to hydrogen gas and their impact on plant growth[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 9(2): 435-444. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01155.x

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Martinez C M, Alvarez L H, Celis L B, et al. Humus-reducing microorganisms and their valuable contribution in environmental processes[J]. Applied Microbiology And Biotechnology, 2013, 97(24): 10293-10308. DOI:10.1007/s00253-013-5350-7

(  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Khdhiri M, Piché-Choquette S, Tremblay J, et al. The tale of a neglected energy source; Elevated hydrogen exposure affects both microbial diversity and function in soil[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2017, 83(11): e00275-17.

(  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Piché-Choquette S, Khdhiri M, Constant P. Dose-response relationships between environmentally-relevant H2 concentrations and the biological sinks of H2, CH4 and CO in soil[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2018, 123: 190-199. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.05.008

(  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Teng Y, Xu Y F, Wang X M, et al. Function of biohydrogen metabolism and related microbial communities in environmental bioremediation[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2019, 10: 106. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00106

(  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Zanaroli G, Negroni A, Häggblom M M, et al. Microbial dehalogenation of organohalides in marine and estuarine environments[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2015, 33: 287-295. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2015.03.013

(  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Jugder B E, Ertan H, Lee M, et al. Reductive dehalogenases come of age in biological destruction of organohalides[J]. Trends in Biotechnology, 2015, 33(10): 595-610. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.07.004

(  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Agarwal V, Miles Z D, Winter J M, et al. Enzymatic halogenation and dehalogenation reactions; Pervasive and mechanistically diverse[J]. Chemical Reviews, 2017, 117(8): 5619-5674. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00571

(  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Brahushi F, Kengara F O, Song Y, et al. Fate processes of chlorobenzenes in soil and potential remediation strategies; A review[J]. Pedosphere, 2017, 27(3): 407-420. DOI:10.1016/S1002-0160(17)60338-2

(  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Jugder B E, Ertan H, Bohl S, et al. Organohalide respiring bacteria and reductive dehalogenases; Key tools in organohalide bioremediation[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 249.

(  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Schubert T, Adrian L, Sawers R G, et al. Organohalide respiratory chains; Composition, topology and key enzymes[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2018, 94(4): fiy035.

(  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Türkowsky D, Jehmlich N, Diekert G, et al. An integrative overview of genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses in organohalide respiration research[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2018, 94(3): fiy013.

(  0) 0) |

| [52] |

Hartwig S, Dragomirova N, Kublik A, et al. A H2‐oxidizing, 1, 2, 3‐trichlorobenzene‐reducing multienzyme complex isolated from the obligately organohalide‐respiring bacterium Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain CBDB1[J]. Environmental Microbiology Report, 2017, 9(5): 618-625. DOI:10.1111/1758-2229.12560

(  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Villemur R, Lanthier M, Beaudet R, et al. The Desulfitobacterium genus[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2006, 30(5): 706-733. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00029.x

(  0) 0) |

| [54] |

Rupakula A, Kruse T, Boeren S, et al. The restricted metabolism of the obligate organohalide respiring bacterium Dehalobacter restrictus; lessons from tiered functional genomics[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Science, 2013, 368(1616): 20120325. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2012.0325

(  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Morris B E L, Henneberger R, Huber H, et al. Microbial syntrophy; Interaction for the common good[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2013, 37(3): 384-406. DOI:10.1111/1574-6976.12019

(  0) 0) |

| [56] |

Vignais P M, Billoud B, Meyer J. Classification and phylogeny of hydrogenases[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2001, 25(4): 455-501. DOI:10.1016/S0168-6445(01)00063-8

(  0) 0) |

| [57] |

Thomas S H, Wagner R D, Arakaki A K, et al. The mosaic genome of Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans strain 2CP-C suggests an aerobic common ancestor to the delta-proteobacteria[J]. PLoS One, 2008, 3(5): e2103. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0002103

(  0) 0) |

| [58] |

Hong Y, Guo J, Sun G. Identification of an uptake hydrogenase for hydrogen-dependent dissimilatory azoreduction by Shewanella decolorationis S12[J]. Applied Microbiology Biotechnology, 2008, 80: 517-524. DOI:10.1007/s00253-008-1597-9

(  0) 0) |

| [59] |

Brigé A, Motte B, Borloo J, et al. Bacterial decolorization of textile dyes is an extracellular process requiring a multicomponent electron transfer pathway[J]. Microbial Biotechnology, 2008, 1(1): 40-52. DOI:10.1111/j.1751-7915.2007.00005.x

(  0) 0) |

| [60] |

Watrous M M, Clark S, Kutty R, et al. 2, 4, 6-Trinitrotoluene reduction by an Fe-only hydrogenase in Clostridium acetobutylicum[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(3): 1542-1547. DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.3.1542-1547.2003

(  0) 0) |

| [61] |

Le Laz S, Kpebe A, Lorquin J, et al. H2-dependent azoreduction by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1;Involvement of secreted flavins and both [Ni-Fe] and [Fe-Fe] hydrogenases[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2014, 98: 2699-2707. DOI:10.1007/s00253-013-5208-z

(  0) 0) |

| [62] |

Xu Y, Teng Y, Wang X, et al. Exploring bacterial community structure and function associated with polychlorinated biphenyl biodegradation in two hydrogen-amended soils[J]. Science of the Total Environmental, 2020, 745: 140839. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140839

(  0) 0) |

| [63] |

Wang Y, Zhang T, Wang J, et al. Regulation of chlorothalonil degradation by molecular hydrogen[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2022, 424: 127291. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127291

(  0) 0) |

| [64] |

Tebo B M, Obraztsova A Y. Sulfate-reducing bacterium grows with Cr(VI), U(VI), Mn(IV), and Fe(III)as electron acceptors[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 1998, 162(1): 193-199. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12998.x

(  0) 0) |

| [65] |

Hussain A, Hasan A L, Javid A, et al. Exploited application of sulfate-reducing bacteria for concomitant treatment of metallic and non-metallic wastes; A mini review[J]. 3 Biotech, 2016, 6(2): 119. DOI:10.1007/s13205-016-0437-3

(  0) 0) |

| [66] |

Deplanche K, Caldelari I, Mikheenko I P, et al. Involvement of hydrogenases in the formation of highly catalytic Pd(0)nanoparticles by bioreduction of Pd(II)using Escherichia coli mutant strains[J]. BMC Microbiology, 2010, 156(9): 2630-2640.

(  0) 0) |

| [67] |

Heidelberg J F, Paulsen I T, Nelson K E, et al. Genome sequence of the dissimilatory metal ion-reducing bacterium Shewanella oneidensis[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2002, 20(11): 1118-1123. DOI:10.1038/nbt749

(  0) 0) |

| [68] |

Zadvorny O A, Zorin N A, Gogotov I N. Transformation of metals and metal ions by hydrogenases from phototrophic bacteria[J]. Archives of Microbiology, 2006, 184(5): 279-285. DOI:10.1007/s00203-005-0040-1

(  0) 0) |

| [69] |

Huang L Y, Liu X, Zhou S G. Direct interspecies electron transfer of microbes; Mechanism and application (In Chinese)[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2018, 55(6): 1313-1324. [黄玲艳, 刘星, 周顺桂. 微生物直接种间电子传递: 机制及应用[J]. 土壤学报, 2018, 55(6): 1313-1324.]

(  0) 0) |

| [70] |

Odom J, Peck H Jr. Hydrogen cycling as a general mechanism for energy coupling in the sulfate-reducing bacteria, Desulfovibrio sp[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 1981, 12(1): 47-50. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1981.tb07609.x

(  0) 0) |

| [71] |

Stams A J M, Plugge C M. Electron transfer in syntrophic communities of anaerobic bacteria and archaea[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2009, 7(8): 568-577. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2166

(  0) 0) |

| [72] |

Lee M, Low A, Zemb O, et al. Complete chloroform dechlorination by organochlorine respiration and fermentation[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 14(4): 883-894. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02656.x

(  0) 0) |

| [73] |

Men Y J, Feil H, VerBerkmoes N C, et al. Sustainable syntrophic growth of Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 with Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough and Methanobacterium congolense; Global transcriptomic and proteomic analyses[J]. The ISME Journal, 2012, 6(2): 410-421. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2011.111

(  0) 0) |

| [74] |

He J Z, Ritalahti K M, Aiello M R, et al. Complete detoxification of vinyl chloride by an anaerobic enrichment culture and identification of the reductively dechlorinating population as a Dehalococcoides species[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(2): 996-1003. DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.2.996-1003.2003

(  0) 0) |

| [75] |

He J Z, Ritalahti K M, Yang K L, et al. Detoxification of vinyl chloride to ethene coupled to growth of an anaerobic bacterium[J]. Nature, 2003, 424(6944): 62-65. DOI:10.1038/nature01717

(  0) 0) |

| [76] |

Ren X Y, Zeng G M, Tang L, et al. Sorption, transport and biodegradation-an insight into bioavailability of persistent organic pollutants in soil[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 610: 1154-1163.

(  0) 0) |

| [77] |

Teng Y, Chen W. Soil microbiomes-a promising strategy for contaminated soil remediation; A review[J]. Pedosphere, 2019, 29(3): 283-297.

(  0) 0) |

| [78] |

Trchounian K, Pinske C, Sawers R G, et al. Dependence on the F0F1-ATP synthase for the activities of the hydrogen-oxidizing hydrogenases 1 and 2 during glucose and glycerol fermentation at high and low pH in Escherichia coli[J]. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes, 2011, 43(6): 645-650.

(  0) 0) |

| [79] |

Cui W T, Gao C Y, Fang P, et al. Alleviation of cadmium toxicity in Medicago sativa by hydrogen-rich water[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2013, 260: 715-724.

(  0) 0) |

| [80] |

Liu S, Li J Y, Oshita S, et al. Formation of a hydrogen radical in hydrogen nanobubble water and its effect on copper toxicity in Chlorella[J]. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2021, 9(33): 11100-11109.

(  0) 0) |

| [81] |

Zhang Q Y, Du S C, Ma Z W, et al. Recent advances in Mg-based hydrogen storage materials (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2022, 67(19): 2158-2171. [张秋雨, 杜四川, 马哲文, 等. 镁基储氢材料的研究进展[J]. 科学通报, 2022, 67(19): 2158-2171.]

(  0) 0) |

2024, Vol. 61

2024, Vol. 61