2. 东北农业大学园艺园林学院, 哈尔滨 150030

2. College of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin 150030, China

随着农业集约化程度和复种指数的增加,土传病虫害爆发、连作障碍现象日趋严重[1-3]。研究表明,根际微生物在帮助植物抵御土传病原物入侵过程中发挥重要作用[4-5]。当遭遇特定的土壤病原物入侵时,植物会采用呼救系统(Cry for help)特异性地调整根系分泌物组分和数量,招募能利用这些特殊物质的有益微生物,以抵御土壤病原菌侵染[6-7]。然而,既然植物具备通过根系分泌物调控自身环境适应性的能力,为什么在连作体系下作物发生土传病害的概率仍然较高?基于植物-土壤反馈理论,连作系统中特定根系分泌物的持续输入可能会起到负面的调节作用。

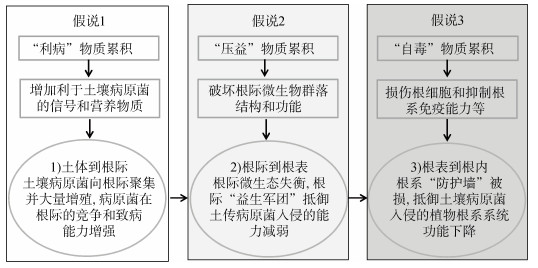

根系分泌物在调控根际微生物结构和功能中发挥重要作用[8],目前研究者多关注于优化根际微生物组或具有抑病功能的根系分泌物组分,但忽略了加剧土传病害发生的物质类型及其可能机制。按照物质类型分类,根系分泌物包括糖类、氨基酸类、有机酸类、酚酸类等[9]。但这些根系分泌物的作用方式、促进土传病害发生的潜在机制尚缺少系统梳理和总结。考虑到连作体系中土传病原菌的致病过程主要包括引入(土体至根际)、定殖(根际至根表)、侵染(根表至根内)三个阶段,连作体系中的根系分泌物可能在土传病原菌入侵植物的各阶段均发挥作用。笔者认为各个阶段加剧土传病原菌入侵的根系分泌物按功能可分为以下三类:(1)利病,有利于土传病原菌在土壤的存活及其由土体向根际的迁移和增殖;(2)压益,破坏根际有益微生物群落;(3)自毒,毒害根系防御系统。为此,本文首先从“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”等三个方面,揭示连作根系分泌物加剧土壤生物障碍的机制以及建立消减“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质的技术途径,可为建立绿色、高效、安全的土传病害综合防控理论和技术提供支撑。

1 根系分泌物中的“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质本文将对病原菌有趋化作用、促进病原菌快速增殖和根际定殖的根系分泌物组分统称为“利病”物质。常报道的根系分泌物中“利病”物质主要有可溶性糖(如葡萄糖、果糖和蔗糖)、有机酸(如苹果酸、柠檬酸、阿魏酸和肉桂酸)、游离氨基酸(如丙氨酸)和类黄酮[10-12]等。例如烟草根系分泌物肉桂酸、肉豆蔻酸和富马酸能够吸引青枯菌并诱导其形成生物膜,增强了青枯菌的趋化性和运动性[13-14]。根际酚酸类物质还可促进土传病原青枯菌的生长和烟草枯萎病的发生,且具有“低促高抑”效应[15]。

根系分泌物中的“压益”物质指扰乱根际微生物群落,抑制有益微生物类群丰度或功能的物质。酚酸类物质是典型的“压益”物质,在连作体系中逐年积累[16]。研究表明这类物质对根际土著微生物的生长有抑制作用,抑制土壤微生物胞外酶的活性(如脲酶、蔗糖酶等)[17]。例如,ρ-羟基苯甲酸/邻苯二甲酸和香草醛的分泌使得根际有益细菌芽孢杆菌属、链霉菌属和溶杆菌属的数量降低,根际微生物群落结构失衡[18-20]。

连作根系分泌物的积累不仅影响根际病原菌和土著微生物的生长与功能,也会直接影响植物的生长和抗性,该类物质称为“自毒”物质。在生长过程中,植物个体通过根系释放的化学代谢产物(根系分泌物),影响其自身和同种植物的生长发育,这种现象被称为“自毒作用”[21]。“自毒”物质可损伤植物根细胞结构和功能,减弱植物根系活力,降低植物抗性[22-24]。这类物质主要是脂肪酸或有机酸类,且其作用效果具有浓度效应。目前根系分泌物中发现的“自毒”物质有烟草中的邻苯二甲酸酯、黄瓜的2,4-二氯苯甲酸和肉桂酸、芋头的苯甲酸以及大豆的苯甲酸、己二酸和对羟基苯乙酸[25-29]。

在非连作情况下,植物也会分泌上述“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质,这类物质随着连作年限的增加而累积,可能会加剧土传病害的发生。连作体系中积累的根系分泌物不仅包括前茬作物根系残体和分泌的物质在土壤中残留,当茬作物根系分泌的物质也会随着根系生长和土壤水分扩散在根际、根表等界面发挥作用,因此,以上三类物质之间存在功能重叠(表 1)。例如,阿魏酸和肉桂酸作为植物典型的自毒物质,同时也能够作为“利病”物质:刺激病原尖孢镰刀菌的孢子萌发,并增加根际镰刀菌的丰度和枯萎病的发病率[30-31]。

|

|

表 1 代表性“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质的来源和功能 Table 1 Sources and functions of representative root exudates that facilitate pathogen, suppress PGPRs and toxic to plant |

土传病原菌侵染作物的前提是能够在土壤存活并在根际定殖,这依赖于土壤和根际中一些能够促进病原菌生长的小分子物质。单一作物连作多年后,某些根系分泌物在土体中逐年积累,对土著微生物具有一定的抑制作用[40-41],但可被土传病原菌高效利用,保障病原菌在休耕土壤中的存活,并在当季促进病原菌的趋化作用和产生物膜能力,病原菌受到这些信号物质(趋化性物质)的刺激后,从土体向寄主植物根际迁移,在根际定殖形成生物膜[42-43],并发挥其致病能力[13](图 1,假说1)。

|

图 1 根系分泌物加剧土传病害发生的假说 Fig. 1 Potential roles of root exudates in exacerbating soil-borne diseases development |

该作用发生的机理主要表现为“利病”物质能够刺激病原菌的孢子萌发和菌丝生长、增强其趋化性、为病原菌提供碳源和增强其毒力相关基因表达[14]。研究发现烟草根系化学信号物质富马酸可吸引土传病原青枯菌并诱导其形成生物膜,两种酚酸(苯甲酸和3-苯丙酸)均能够促进青枯菌的生长,而肉桂酸和肉豆蔻酸可通过诱导青枯菌的趋化性和运动相关基因的表达对其群集运动和趋化性起重要作用[14,20]。而土传病原真菌的根系定殖与根分泌物中的糖、脂肪酸和糖醇相关,如黄瓜、大豆、马铃薯连作后的根分泌物中的L-阿拉伯糖醇、棉子糖、异黄酮、氨基酸以及柠檬酸、棕榈酸、邻苯二甲酸二丁酯、邻苯二甲酸和丙二酸等有机酸含量逐年增高,上述分泌物能够显著促进尖孢镰刀菌、疫霉菌和立枯丝核菌的孢子趋化、萌发和根际定殖[32-35](表 1)。土传病原菌(如土传青枯菌)可代谢酚类自毒物质,而该能力对病原菌的致病过程是必不可少的[44-45]。病原菌对自毒物质的降解与利用可能是病原菌在与土著微生物竞争中获得优势、进而致病的关键[46-47]。因此,连作体系下作物根系分泌物中“利病”物质的累积,会促进病原菌向植物根际聚集并大量增殖,使其在植物根际存活的能力增强,更具竞争力。

2.2 “压益”:破坏根际微生物组的物质积累土壤微生物群落是帮助植物根际抵御病原菌入侵的重要防线[4-5]。这些微生物保护寄主的主要机制是通过与病原菌竞争营养物质和生态位点,产生拮抗性物质,诱导寄主抗性[48]。通常认为土著有益微生物类群生物量降低、群落结构失衡是连作系统土传病害爆发的重要原因。相比轮作等其他种植方式,连作土壤中芽孢杆菌、酸杆菌、链霉菌、黄杆菌和黄单胞菌等有益微生物丰度降低,群落内部互作关系减弱,而乳酸菌、伯克霍尔德菌、腐生真菌、镰刀菌和曲霉菌等病原微生物的丰度增高[49-52]。

连作积累的根系分泌物可通过抑制根际有益微生物丰度,使群落产抑菌次生代谢物的能力减弱,同时根际有益微生物的丰度降低,释放出大量生态位,增加土传病原菌的入侵概率[37,46-47,53](图 1,假说2)。Zhao等[37]发现太子参根系分泌物中异黄酮含量随着连作年限增加而不断上升,显著改变了根际土壤微生物群落的多样性和结构,使得病原菌与有益细菌的比例增加,从而导致太子参根际的微生态失衡和连作障碍的发生。更多的研究发现,外源添加“压益”物质阿魏酸和对羟基苯甲酸等酚类物质可改变黄瓜根际微生物群落结构、降低细菌群落多样性,选择性地抑制了黄瓜根际有益菌群[53];土壤中添加人参自毒皂苷物质会富集潜在的致病真菌类群,如链格孢属、赤霉属和镰刀菌属,并降低了有益真菌类群的丰度,如支顶孢属和毛霉属[47];“压益”代谢物醋酸生育酚、瓜氨酸、半乳糖醇、十八烷基甘油和山萮酸等驱动的感病土壤中,一些具备降解自毒物质能力的细菌(如慢生根瘤菌属、链霉菌属、贪噬菌属)丰度下降,但招募了一些代谢小分子糖和酸的细菌(厌氧菌属、蛭弧菌属和黄杆菌属)[54]。此外,根系分泌物“压益”的作用也会进一步影响下茬作物的生长。外源添加香豆酸减低了根际有益微生物的多样性,富集了可利用酚酸的真菌类群,加剧了病害的发生,同时阻碍了下茬植株幼苗对有益菌的招募,影响幼苗生长[55]。

2.3 “自毒”:破坏根系免疫能力的物质积累正常情况下根系分泌物中的自毒物质对植物自身不会产生明显的负面作用,但自毒物质的持续积累同样会对自身造成伤害,影响植物生长和系统抗性。连作体系中酚酸类自毒物质,如羟基苯甲酸的含量随着连作年限的增加而不断累积,不仅抑制作物自身的生长,还加剧了病害的发生[13,56]。花生结荚期根系分泌物中的苯乙酮能够促进花生青枯病菌的生长,同时对花生种子胚根的伸长、幼苗生长等有抑制作用,并且该促进和抑制作用均随根系分泌物添加浓度和连作年限的增加呈增强趋势[57]。根系组织是植物抵御土传病原菌入侵的最后一道防线,自毒物质对植物根系造成的生理毒害,如损伤植物根系细胞膜通透性、根系活力和系统抗性等能力,使其抵御病原菌入侵的最后一道“防线”破损,难以阻碍病原菌的入侵,最终加剧土传病害的爆发(图 1,假说3)。

常报道的根系分泌物自毒物质包括黄瓜的2,4-二氯苯甲酸和肉桂酸[25]、人参中的苯甲酸[58]、三七中的人参皂苷[59]。这些物质对植物生长和抗性的影响机制主要有:(1)通过诱导过氧化氢和活性氧的过度积累、影响抗氧化防御系统酶活性、破坏细胞壁和改变细胞膜的渗透性,抑制根系生长和阻碍养分吸收[60];(2)抑制有丝分裂和细胞周期相关基因的表达,造成细胞分裂和伸长减缓、胚根生长受到抑制,从而影响植物的生长发育[61];(3)减少叶片蒸腾作用,降低胞间CO2浓度,降低参与光合电子传输链、光合磷酸化和卡尔文循环相关基因的表达,导致植物碳水化合物水平降低[62-63]。

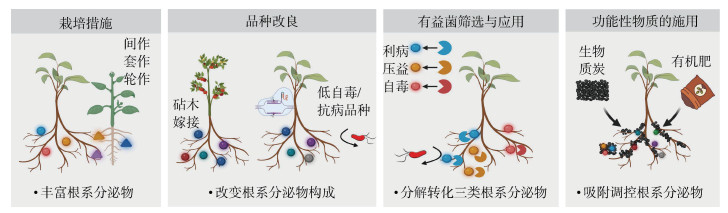

3 基于根系分泌物的连作障碍缓解策略品种改良、多样性种植方式以及有机肥施加等措施已被证明可缓解连作土传病害的发生,但较少通过根系分泌物角度来探究其调控机制。因此本文针对“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”三大类根系分泌物,提出以下4种缓解连作障碍的策略(图 2)。

|

图 2 基于根系分泌物的连作障碍缓解策略 Fig. 2 Strategies for redacting continuous cropping disorder by management of root exudation |

间套作和轮作被证明是有效缓解土传病害的措施,主要通过间作、套作、轮作和填闲等方式增加种植体系中作物的种类,或者利用不同作物生长的时间差和空间差,种植一种或多种作物(图 2,栽培措施);还包括在主栽作物种植密度不变的情况下,小规模种植能够帮助主作物降低病虫害、缓解连作障碍的伴生植物。研究表明,间套作和轮作主要通过以下三个方面缓解主栽作物土壤生物障碍。

3.1.1 提高根际分泌物多样性花生连续单作会降低根系沉积物的化学多样性,从而抑制利用根系沉积物的微生物群落的生物多样性和功能[64]。花生与棉花的轮作增加了根系分泌物的多样性和微生物群落的结构和功能,显著提高了花生籽粒总蛋白和油酸含量[65]。

3.1.2 减少主栽作物分泌自毒物质大蒜与番茄的间作可缓解番茄连作障碍,是由于大蒜根系分泌物中的二烯丙基二硫化物(DADS)不仅可降低番茄根系分泌物中自毒物质脂肪酸酯(例如棕榈酸甲酯、棕榈烯酸甲酯、油酸甲酯)的含量,还可提高番茄植株的根系活性和抗氧化酶含量[39]。在番茄洋葱间作体系的番茄中与发病相关蛋白、木质素生物合成、激素代谢和信号转导相关的防御抗病基因的表达均高于番茄单作[66]。

3.1.3 分泌“抑病”根系分泌物罗勒作为伴生植物,不仅显著提高了主栽作物番茄的产量,其根系分泌物迷迭香酸能够降低土传病害的发生[67-68]。万寿菊可通过其化感作用抑制番茄早疫病菌分生孢子萌发来降低番茄枯萎病的发生[69]。芝麻、花生、番茄等作物与葱轮作可有效降低寄主作物青枯病发生程度,葱根系分泌物中的大蒜新素、大蒜辣素等多硫化合物对青枯菌具有较强的抑制能力[70]。在分蘖洋葱的伴生系统中,分蘖洋葱根系分泌物花旗松素能够刺激番茄植株招募植物有益菌,如芽孢杆菌属的定殖,增强根际微生物组的抑病力,以防控土传病原大丽轮枝菌引起的黄萎病[71]。

综上,选择合适的轮作或间作作物可调控植物向地下生态系统输入根系分泌物的数量和构成,对修复土壤微生物群落结构、改善植物生长和降低病害发生至关重要。

3.2 品种改良目前一些研究还发现采用抗病砧木嫁接作物、筛选低自毒和抗病基因型品种可调控根系分泌物,进而实现土传连作障碍的消减(图 2,品种改良)。

3.2.1 嫁接将高感青枯病的番茄品种嫁接至茄子砧木上可显著降低樱桃番茄青枯病的发病率,并且改善了嫁接植株根际微环境[72]。同时,嫁接后番茄根系分泌物能够显著促进番茄幼苗的生长,并且抑制青枯菌的增殖[73]。此外,嫁接通过根系分泌物的直接拮抗作用和形成保护性的根际微生物菌群间接增强植物抗病性。例如,嫁接西瓜根系分泌物中的有机酸(潜在的自毒素)显著减少,而植物防御相关代谢产物,如有机硫化合物和苯类化合物显著富集;嫁接后根际土壤中镰刀菌的丰度显著降低,同时潜在的有益细菌类群,如链霉菌和鞘氨醇单胞菌在嫁接西瓜根际显著富集[74]。

3.2.2 低自毒和抗病品种筛选低自毒和抗病基因型品种,可通过调控植物代谢物的合成途径来降低三类物质的合成,从而减轻作物连作障碍。王梓等[38]研究表明,转录因子WRKY7在人参响应化感自毒物质苯甲酸胁迫的过程中表达量显著上调,表明该基因参与了人参响应苯甲酸胁迫的过程。Bu等[75]利用病毒诱导基因沉默(VIGS)系统成功地沉默了黄瓜中的甘油-3-磷酸酰基转移酶6基因(GPAT6),从而减轻根系分泌物肉桂酸对黄瓜的自毒作用。

3.3 有益菌筛选与应用采用生物降解技术是克服植物“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”三大类物质的一种有效措施[76](图 2,有益菌筛选与应用)。主要指从土壤中分离出一些具有分解植物“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”三类物质能力的细菌,从而缓解作物的连作障碍[77]。球形节杆菌和恶臭假单胞菌等菌株能够降解阿魏酸、对羟基苯甲酸、丁香酸等对百合、西瓜、杨树、草莓和桃树幼苗生长有自毒作用的根系分泌物[78-79]。根际分离的伯克霍尔德菌株B36能够利用三七分泌的自毒物质人参皂苷,用于自身生长和生物膜的形成,增强对病原菌的拮抗能力和在根际土壤中的定殖能力[80]。

3.4 功能性物质的施用生物质炭、有机肥等功能性物质也能通过直接或间接调控根系分泌物来缓解作物连作障碍(图 2,功能性物质的施用)。例如,生物质炭能吸附土壤中的有害物质,降低田间自毒物质的含量,减弱自毒物质对植物生长的影响,并增加有益菌的生物量、生长速率和产孢量[81-82]。研究表明,生物质炭通过增强番茄根系分泌物对有益微生物的趋化性和促进生物膜形成的能力,从而帮助番茄有效地招募抑病型根际微生物组来防控枯萎病[83]。生物质炭联合植物根际促生菌(PGPBs)通过调控根系分泌物,促进土著有益微生物大量增殖,抑制土传病害发生,进而减缓太子参连作障碍[84]。有机肥可促进根际假单胞菌、芽孢杆菌等有益微生物的定殖和相互作用,增强多菌种生物膜在根-微生物组界面的组装来保护植物免受病原菌侵染[85]。由芽孢杆菌等功能菌株制备的生物有机肥能够通过调节土壤理化性质、根际微生物群落和降低病原菌数量,消减西瓜和花生的连作障碍[86-87]。此外,氨基酸肥料的施加能够通过激发土壤微生物活性,降低尖孢镰刀菌的丰度来缓解黄瓜连作障碍[36]。磷石膏专用复混肥的施用不仅可显著提高红壤地区花生产量,还可有效缓解连作障碍[88]。

4 展望根系分泌物对植物的影响具有两面性,既可招募有益微生物促进生长,也累积有害物质阻碍植物根系发育和养分吸收并加剧病害发生。目前在利用有益微生物增强植物抗病能力或优化根际微生物群落等方面解决连作障碍的研究取得了较大的进展,进一步系统鉴定“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质,探究其在介导“植物-土壤-微生物”反馈互作中的作用机制,建立相应的根际靶向调控策略,对连作土传病害的综合解决具有重要意义。

4.1 连作体系中“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质的鉴定鉴定并验证“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质及其对植物、病原菌和根际有益菌的作用机制;基于对不同作物及不同品种“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”根系分泌物组分的鉴定结果,针对性地选择种植作物品种,制定合理的种植模式。此外,三类物质鉴定过程中,尤其是“利病”物质鉴定,要注重相对性,尤其是对于病原菌相比其他土著微生物具有更强促进作用的碳源。

4.2 三大类物质消减措施下的“植物-土壤-微生物”反馈互作机制研究多样性种植、嫁接、生物质炭和有机肥施用等措施下根系分泌物的种类和浓度,从“植物-土壤”互作角度,建立“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质与植物激素、关键基因表达以及根际关键微生物的关系,阐明调控和消减三大类根系分泌物影响植物养分吸收、生长发育、系统抗性以及微生物组的机制。

4.3 “利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质的根际靶向调控策略构建靶向消减“利病”、“压益”和“自毒”物质的技术,可高效降低连作土传病害。例如,筛选定向利用或降解三大类物质的根际微生物,构建可同时降解“利病”“压益”和“自毒”物质的根际合成菌群。此外,基于对三大类物质种类合成代谢途径的解析,对作物进行基因靶向改造,定向培育产三大类物质较少、抗病物质较多的作物品种。

| [1] |

Liu J J, Yao Q, Li Y S, et al. Continuous cropping of soybean alters the bulk and rhizospheric soil fungal communities in a Mollisol of Northeast, PR China[J]. Land Degradation & Development, 2019, 30(14): 1725-1738.

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Zheng G D, Shi L B, Wu H Y, et al. Nematode communities in continuous tomato-cropping field soil infested by root-knot nematodes[J]. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B - Soil & Plant Science, 2012, 62(3): 216-223.

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Davis J R, Pavek J J, Corsini D L, et al. Influence of continuous cropping of several potato clones on the epidemiology of Verticillium wilt of potato[J]. Phytopathology, 1994, 84(2): 207-214. DOI:10.1094/Phyto-84-207

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Sanguin H, Sarniguet A, Gazengel K, et al. Rhizosphere bacterial communities associated with disease suppressiveness stages of take-all decline in wheat monoculture[J]. New Phytologist, 2009, 184(3): 694-707. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03010.x

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Zhou X, Wang J T, Liu F, et al. Cross-kingdom synthetic microbiota supports tomato suppression of Fusarium wilt disease[J]. Nature Communications, 2022, 13(1): 7890. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-35452-6

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Yuan J, Zhao J, Wen T, et al. Root exudates drive the soil-borne legacy of aboveground pathogen infection[J]. Microbiome, 2018, 6(1): 1-12. DOI:10.1186/s40168-017-0383-2

(  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Hu L F, Robert C A M, Cadot S, et al. Root exudate metabolites drive plant-soil feedbacks on growth and defense by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota[J]. Nature Communications, 2018, 9(1): 2738. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-05122-7

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Sasse J, Martinoia E, Northen T. Feed your friends: Do plant exudates shape the root microbiome?[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2018, 23(1): 25-41. DOI:10.1016/j.tplants.2017.09.003

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Gu Y, Wang X F, Yang T J, et al. Chemical structure predicts the effect of plant-derived low-molecular weight compounds on soil microbiome structure and pathogen suppression[J]. Functional Ecology, 2020, 34(10): 2158-2169. DOI:10.1111/1365-2435.13624

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Wang X Z, Wu F Z, Han X. Effects of sugars on germination and mycelium growth of Fusarium Oxysporum[J]. Allelopathy Journal, 2007, 20(2): 339-345.

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Wu K, Su L, Fang Z Y, et al. Competitive use of root exudates by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens with Ralstonia solanacearum decreases the pathogenic population density and effectively controls tomato bacterial wilt[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2017, 218: 132-138. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2017.01.047

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Hofmann A, Wittenmayer L, Arnold G, et al. Root exudation of phloridzin by apple seedlings(Malus x domestica Borkh.)with symptoms of apple replant disease[J]. Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality, 2009, 82(2): 193-198.

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Chen S L, Zhou B L, Lin S S, et al. Accumulation of cinnamic acid and vanillin in eggplant root exudates and the relationship with continuous cropping obstacle[J]. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2011, 10(14): 2659-2665. DOI:10.5897/AJB10.1338

(  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Li S L, Xu C, Wang J, et al. Cinnamic, myristic and fumaric acids in tobacco root exudates induce the infection of plants by Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. Plant and Soil, 2017, 412(1): 381-395.

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Liu Y X, Li X, Cai K, et al. Identification of benzoic acid and 3-phenylpropanoic acid in tobacco root exudates and their role in the growth of rhizosphere microorganisms[J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2015, 93: 78-87. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2015.04.009

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Bai Y X, Yang C C, Shi P Y, et al. Correlation analysis of main environmental factors and phenolic acids in continuous tobacco cropping soils using Mantel Test (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture, 2019, 27(3): 369-379. [白羽祥, 杨成翠, 史普酉, 等. 连作植烟土壤酚酸类物质变化特征及其与主要环境因子的Mantel Test分析[J]. 中国生态农业学报, 2019, 27(3): 369-379.]

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Cui J J, Zhang E H, Zhang X H, et al. Effects of 2, 4-di-tert-butylphenol at different concentrations on soil functionality and microbial community structure in the Lanzhou lily rhizosphere[J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2022, 172: 104367. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104367

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Liu Q W, Zhang L H, Wang L, et al. Autotoxin affects the rhizosphere microbial community structure by influencing the secretory characteristics of grapevine roots[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2022, 13: 953424. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.953424

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Hua C P, Xie Z K, Wu Z J, et al. The physiological and biochemical effects of phthalic acids and the changes of rhizosphere fungi diversity under continuous cropping of Lanzhou lily(Lilium davidii var. unicolor)[J]. HortScience, 2019, 54(2): 253-261. DOI:10.21273/HORTSCI13527-18

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Zhou X G, Wu F Z. Vanillic acid changed cucumber(Cucumis sativus L.)seedling rhizosphere total bacterial, Pseudomonas and Bacillus spp. communities[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8: 4929. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-23406-2

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Rice E L. Allelopathy—an update[J]. The Botanical Review, 1979, 45(1): 15-109. DOI:10.1007/BF02869951

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Cao P R, Liu C Y, Li D. Effects of different autotoxins on antioxidant enzymes and chemical compounds in tea(Camellia sinensis L.)Kuntze[J]. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2011, 10(38): 7480-7486.

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Zhou X, Yu G, Wu F. Soil phenolics in a continuously mono-cropped cucumber(Cucumis sativus L.)system and their effects on cucumber seedling growth and soil microbial communities[J]. European Journal of Soil Science, 2012, 63(3): 332-340. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2389.2012.01442.x

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Feng J, Zhou B Q, Liu Q, et al. Study on the relationship between rhizosphere microorganism and phenolic acids and its countermeasures (In Chinese)[J]. China Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, 2020, 35(8): 4049-4052. [冯静, 周冰谦, 刘谦, 等. 药用植物根际微生物与酚酸类自毒物质致害机制及作用关系研究[J]. 中华中医药杂志, 2020, 35(8): 4049-4052.]

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Asao T, Kitazawa H, Tomita K, et al. Mitigation of cucumber autotoxicity in hydroponic culture using microbial strain[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2004, 99(3/4): 207-214.

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Deng J J, Zhang Y L, Hu J W, et al. Autotoxicity of phthalate esters in tobacco root exudates: Effects on seed germination and seedling growth[J]. Pedosphere, 2017, 27(6): 1073-1082. DOI:10.1016/S1002-0160(17)60374-6

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Meng X, Luo S L, Dawuda M M, et al. Exogenous silicon enhances the systemic defense of cucumber leaves and roots against CA-induced autotoxicity stress by regulating the ascorbate-glutathione cycle and photosystem Ⅱ[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2021, 227: 112879. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112879

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Asao T, Hasegawa K, Sueda Y, et al. Autotoxicity of root exudates from taro[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2003, 97(3/4): 389-396.

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Asaduzzaman M, Asao T. Autotoxicity in beans and their allelochemicals[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2012, 134: 26-31. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2011.11.035

(  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Ren L X, Huo H W, Zhang F, et al. The components of rice and watermelon root exudates and their effects on pathogenic fungus and watermelon defense[J]. Plant Signaling & Behavior, 2016, 11(6): e1187357.

(  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Zhou X G, Wu F Z. Effects of amendments of ferulic acid on soil microbial communities in the rhizosphere of cucumber(Cucumis sativus L.)[J]. European Journal of Soil Biology, 2012, 50: 191-197. DOI:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2012.03.001

(  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Zhang W M, Qiu H Z, Zhang C H, et al. Identification of chemicals in root exudates of potato and their effects on Rhizoctonia solani (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2015, 26(3): 859-866. [张文明, 邱慧珍, 张春红, 等. 马铃薯根系分泌物成分鉴别及其对立枯丝核菌的影响[J]. 应用生态学报, 2015, 26(3): 859-866.]

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Ju H Y, Han L M, Wang S Q, et al. Allelopathic effect of root exudates on pathogenic fungi of root rot in continuous cropping soybean (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2002, 13(6): 723-727. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-9332.2002.06.019 [鞠会艳, 韩丽梅, 王树起, 等. 连作大豆根分泌物对根腐病病原菌的化感作用[J]. 应用生态学报, 2002, 13(6): 723-727.]

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Zhang Z Q, Xu Y, Song G M, et al. Phytophthora sojae zoospores differ in chemotaxis to the root and root exudates of host soybean and nonhost common bean[J]. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 2019, 85(3): 201-210. DOI:10.1007/s10327-019-00839-9

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Liu Y P, Chen L, Wu G W, et al. Identification of root-secreted compounds involved in the communication between cucumber, the beneficial Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, and the soil-borne pathogen Fusarium oxysporum[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2017, 30(1): 53-62. DOI:10.1094/MPMI-07-16-0131-R

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Zhang S S, Yang X M, Huang Q W, et al. Effect of application of amino acid fertilizer on biological properties of cucumber plants and soil microorganisms under continuous mono-cropping (In Chinese)[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2007, 44(4): 689-694. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0564-3929.2007.04.016 [张树生, 杨兴明, 黄启为, 等. 施用氨基酸肥料对连作条件下黄瓜的生物效应及土壤生物性状的影响[J]. 土壤学报, 2007, 44(4): 689-694.]

(  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Zhao Y P, Lin S, Chu L X, et al. Insight into structure dynamics of soil microbiota mediated by the richness of replanted Pseudostellaria heterophylla[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1038/s41598-016-0001-8

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Wang Z, Li Y, Wang R, et al. Gene cloning and expression analysis of benzoic acid stress responsive transcription factor WRKY7 in Panax ginseng (In Chinese)[J]. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica, 2017, 42(6): 1130-1135. [王梓, 李勇, 王蓉, 等. 人参中苯甲酸胁迫响应基因WRKY7的克隆与表达分析[J]. 中国中药杂志, 2017, 42(6): 1130-1135.]

(  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Cheng F, Ali M, Liu C, et al. Garlic allelochemical diallyl disulfide alleviates autotoxicity in the root exudates caused by long-term continuous cropping of tomato[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020, 68(42): 11684-11693. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c03894

(  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Li X G, Ding C F, Hua K, et al. Soil sickness of peanuts is attributable to modifications in soil microbes induced by peanut root exudates rather than to direct allelopathy[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2014, 78: 149-159. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.07.019

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Xiong W, Zhao Q Y, Zhao J, et al. Different continuous cropping spans significantly affect microbial community membership and structure in a Vanilla-grown soil as revealed by deep pyrosequencing[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2015, 70(1): 209-218. DOI:10.1007/s00248-014-0516-0

(  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Amponsah J, Tegg R S, Thangavel T, et al. Moments of weaknesses–exploiting vulnerabilities between germination and encystment in the Phytomyxea[J]. Biological Reviews, 2021, 96(4): 1603-1615. DOI:10.1111/brv.12717

(  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Zhang H, Yang Y X, Mei X Y, et al. Phenolic acids released in maize rhizosphere during maize-soybean intercropping inhibit Phytophthora blight of soybean[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2020, 11: 886. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2020.00886

(  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Lowe T M, Ailloud F, Allen C. Hydroxycinnamic acid degradation, a broadly conserved trait, protects Ralstonia solanacearum from chemical plant defenses and contributes to root colonization and virulence[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2015, 28(3): 286-297. DOI:10.1094/MPMI-09-14-0292-FI

(  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Zhang Y, Zhang W Q, Han L L, et al. Involvement of a PadR regulator PrhP on virulence of Ralstonia solanacearum by controlling detoxification of phenolic acids and type Ⅲ secretion system[J]. Molecular Plant Pathology, 2019, 20(11): 1477-1490. DOI:10.1111/mpp.12854

(  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Xu Y G, Yang M, Yin R, et al. Autotoxin Rg1 induces degradation of root cell walls and aggravates root rot by modifying the rhizospheric microbiome[J]. Microbiology Spectrum, 2021, 9(3): e01679-21.

(  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Li Y L, Dai S Y, Wang B Y, et al. Autotoxic ginsenoside disrupts soil fungal microbiomes by stimulating potentially pathogenic microbes[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2020, 86(9): e00130-20.

(  0) 0) |

| [48] |

O'Brien P A. Biological control of plant diseases[J]. Australasian Plant Pathology, 2017, 46(4): 293-304. DOI:10.1007/s13313-017-0481-4

(  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Xu X J, Luo Q Y, Wei Q C, et al. The deterioration of agronomical traits of the continuous cropping of Stevia is associated with the dynamics of soil bacterial community[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2022, 13: 917000. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.917000

(  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Bao Y, Qi B, Huang W, et al. The fungal community in non-rhizosphere soil of Panax ginseng are driven by different cultivation modes and increased cultivation periods[J]. PeerJ, 2020, 8: e9930. DOI:10.7717/peerj.9930

(  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Li H Y, Li C H, Song X, et al. Impacts of continuous and rotational cropping practices on soil chemical properties and microbial communities during peanut cultivation[J]. Scientific Reports, 2022, 12(1): 2758. DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-06789-1

(  0) 0) |

| [52] |

Ali A, Elrys A S, Liu L L, et al. Cover plants-mediated suppression of Fusarium wilt and root-knot incidence of cucumber is associated with the changes of rhizosphere fungal microbiome structure-under plastic shed system of North China[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2022, 13: 697815. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.697815

(  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Jin X, Wu F Z, Zhou X G. Different toxic effects of ferulic and p-hydroxybenzoic acids on cucumber seedling growth were related to their different influences on rhizosphere microbial composition[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2020, 56(1): 125-136. DOI:10.1007/s00374-019-01408-0

(  0) 0) |

| [54] |

Wen T, Xie P H, Penton C R, et al. Specific metabolites drive the deterministic assembly of diseased rhizosphere microbiome through weakening microbial degradation of autotoxin[J]. Microbiome, 2022, 10(1): 177. DOI:10.1186/s40168-022-01375-z

(  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Zhou X G, Zhang J H, Pan D D, et al. p-Coumaric can alter the composition of cucumber rhizosphere microbial communities and induce negative plant-microbial interactions[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2018, 54(3): 363-372. DOI:10.1007/s00374-018-1265-x

(  0) 0) |

| [56] |

Li H Q, Liu Q Z, Zhang L L, et al. Accumulation of phenolic acids in the monocultured strawberry soils and their effect on soil nematodes (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 2014, 33(1): 169-175. [李贺勤, 刘奇志, 张林林, 等. 草莓连作土壤酚酸类物质积累对土壤线虫的影响[J]. 生态学杂志, 2014, 33(1): 169-175.]

(  0) 0) |

| [57] |

Wang X B, Luo Y M, Liu W X, et al. Identification of peanut root exudates and their allelopathic effects (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 2011, 30(12): 2803-2808. [王小兵, 骆永明, 刘五星, 等. 花生根系分泌物的鉴定及其化感作用[J]. 生态学杂志, 2011, 30(12): 2803-2808.]

(  0) 0) |

| [58] |

Li Y, Huang X F, Ding W L. Autotoxicity of Panax ginseng rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil extracts on early seedlings growth and identification of chemicals[J]. Allelopathy Journal, 2011, 28(2): 145-154.

(  0) 0) |

| [59] |

Yang M, Zhang X D, Xu Y G, et al. Autotoxic ginsenosides in the rhizosphere contribute to the replant failure of Panax notoginseng[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(2): e0118555. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0118555

(  0) 0) |

| [60] |

Yang M, Chuan Y C, Guo C W, et al. Panax notoginseng root cell death caused by the autotoxic ginsenoside Rg1 is due to over-accumulation of ROS, as revealed by transcriptomic and cellular approaches[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2018, 9: 264. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2018.00264

(  0) 0) |

| [61] |

Zhang Y, Gu M, Shi K, et al. Effects of aqueous root extracts and hydrophobic root exudates of cucumber(Cucumis sativus L.)on nuclei DNA content and expression of cell cycle-related genes in cucumber radicles[J]. Plant and Soil, 2010, 327(1): 455-463.

(  0) 0) |

| [62] |

Yu J Q, Ye S F, Zhang M F, et al. Effects of root exudates and aqueous root extracts of cucumber(Cucumis sativus)and allelochemicals, on photosynthesis and antioxidant enzymes in cucumber[J]. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, 2003, 31(2): 129-139. DOI:10.1016/S0305-1978(02)00150-3

(  0) 0) |

| [63] |

Liang G T, Niu Y J. The allelopathic effect of para-hydroxybenzoic acid on the gene expression of photosynthesis and respiration in Solanum lycopersicum[J]. Current Plant Biology, 2022, 32: 100261. DOI:10.1016/j.cpb.2022.100261

(  0) 0) |

| [64] |

Li P, Liu J, Saleem M, et al. Reduced chemodiversity suppresses rhizosphere microbiome functioning in the mono-cropped agroecosystems[J]. Microbiome, 2022, 10(1): 108. DOI:10.1186/s40168-022-01287-y

(  0) 0) |

| [65] |

Lu J, Liu Y, Zou X, et al. Rotational strip peanut/cotton intercropping improves agricultural production through modulating plant growth, root exudates, and soil microbial communities[J]. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2024, 359: 108767.

(  0) 0) |

| [66] |

Fu X P, Wu X, Zhou X G, et al. Companion cropping with potato onion enhances the disease resistance of tomato against Verticillium dahliae[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2015, 6: 726.

(  0) 0) |

| [67] |

Bais H P, Walker T S, Schweizer H P, et al. Root specific elicitation and antimicrobial activity of rosmarinic acid in hairy root cultures of Ocimum basilicum[J]. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 2002, 40(11): 983-995. DOI:10.1016/S0981-9428(02)01460-2

(  0) 0) |

| [68] |

Bhuiya M I, Rahman M A, Miah M M U, et al. Gliricidia tree leaf incorporation into soil and use of companion plants for safe tomato production[J]. Journal of the Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University, 2020, 65(1): 1-7. DOI:10.5109/2558881

(  0) 0) |

| [69] |

Gómez-Rodrı́guez O, Zavaleta-Mejı́a E, González- Hernández V A, et al. Allelopathy and microclimatic modification of intercropping with marigold on tomato early blight disease development[J]. Field Crops Research, 2003, 83(1): 27-34. DOI:10.1016/S0378-4290(03)00053-4

(  0) 0) |

| [70] |

Li X S, Shao H, Chen J, et al. Root colonization of Ralstonia solanacearum in different crops and crop rotation systems for plant disease control (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Oil Crop Sciences, 2020, 42(4): 667-673. [李信申, 邵华, 陈建, 等. 青枯雷尔氏菌在不同作物根际定殖与轮作防病[J]. 中国油料作物学报, 2020, 42(4): 667-673.]

(  0) 0) |

| [71] |

Zhou X G, Zhang J Y, Muhammad Khashi u R, et al. Interspecific plant interaction via root exudates structures the disease suppressiveness of rhizosphere microbiomes[J]. Molecular Plant, 2023, 16(5): 849-864. DOI:10.1016/j.molp.2023.03.009

(  0) 0) |

| [72] |

Zhao W Z, Zheng X Y, Zhang Y Q, et al. Effects of two rootstocks on bacterial wilt resistance and rhizospheric microorganisms of cherry tomato (In Chinese)[J]. Guihaia, 2019, 39(10): 1307-1316. DOI:10.11931/guihaia.gxzw201812009 [赵文宗, 郑旭阳, 张映卿, 等. 两种砧木对樱桃番茄青枯病抗性及根际微生物数量的影响[J]. 广西植物, 2019, 39(10): 1307-1316.]

(  0) 0) |

| [73] |

Zhao W Z, Zheng X Y, Zhang Y Q, et al. Effects of root exudates from tomato grafted with different rootstocks on Ralstonia solanacearum and seedling growth (In Chinese)[J]. China Vegetables, 2019(5): 58-63. [赵文宗, 郑旭阳, 张映卿, 等. 不同砧木嫁接番茄根系分泌物对青枯病菌和幼苗生长的影响[J]. 中国蔬菜, 2019(5): 58-63.]

(  0) 0) |

| [74] |

Ge A H, Liang Z H, Han L L, et al. Rootstock rescues watermelon from Fusarium wilt disease by shaping protective root-associated microbiomes and metabolites in continuous cropping soils[J]. Plant and Soil, 2022, 479(1): 423-442.

(  0) 0) |

| [75] |

Bu R F, Wang R H, Wei Q C, et al. Silencing of glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 6(GPAT6)gene using a newly established virus induced gene silencing(VIGS)system in cucumber alleviates autotoxicity mimicked by cinnamic acid(CA)[J]. Plant and Soil, 2019, 438(1): 329-346.

(  0) 0) |

| [76] |

Wu F Z, Zhao F Y, Ma F M. Phenolic acid substances and allelopathy mechanisms (In Chinese)[J]. Journal of Northeast Agricultural University, 2001, 32(4): 402-407. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-9369.2001.04.014 [吴凤芝, 赵凤艳, 马凤鸣. 酚酸物质及其化感作用[J]. 东北农业大学学报, 2001, 32(4): 402-407.]

(  0) 0) |

| [77] |

Li Y, Long Q L, Ding W L, et al. Mitigative effect of micribial degradation on autotoxicity of Panax ginseng (In Chinese)[J]. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica, 2014, 39(15): 2868-2872. [李勇, 龙期良, 丁万隆, 等. 微生物降解对人参自毒作用的缓解效应[J]. 中国中药杂志, 2014, 39(15): 2868-2872.]

(  0) 0) |

| [78] |

Wang Y, Zhang W, Zhang Z, et al. Isolation, identification and characterization of phenolic acid- degrading bacteria from soil[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2021, 131(1): 208-220. DOI:10.1111/jam.14956

(  0) 0) |

| [79] |

He H, Zhu W, Noor I, et al. Pseudomonas putida WH-B3 degrades benzoic acid and alleviates its autotoxicity to peach(Prunus persica L. batsch)seedlings grown in replanted soil[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2019, 255: 183-192. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.05.020

(  0) 0) |

| [80] |

Luo L F, Wang L T, Deng L M, et al. Enrichment of Burkholderia in the rhizosphere by autotoxic ginsenosides to alleviate negative plant-soil feedback[J]. Microbiology Spectrum, 2021, 9(3): e01400-21.

(  0) 0) |

| [81] |

Wang W P, Wang Z H, Yang K, et al. Biochar application alleviated negative plant-soil feedback by modifying soil microbiome[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2020, 11: 799. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2020.00799

(  0) 0) |

| [82] |

Ma Z T, Wang Q, Wang X W, et al. Effects of biochar on replant disease by amendment soil environment[J]. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis, 2021, 52(7): 673-685. DOI:10.1080/00103624.2020.1869758

(  0) 0) |

| [83] |

Jin X, Bai Y, Khashi u Rahman M, et al. Biochar stimulates tomato roots to recruit a bacterial assemblage contributing to disease resistance against Fusarium wilt[J]. iMeta, 2022, 1(3): e37. DOI:10.1002/imt2.37

(  0) 0) |

| [84] |

Wu H M, Wu H M, Jiao Y Y, et al. The combination of biochar and PGPBs stimulates the differentiation in rhizosphere soil microbiome and metabolites to suppress soil-borne pathogens under consecutive monoculture regimes[J]. Global Change Biology Bioenergy, 2022, 14(1): 84-103. DOI:10.1111/gcbb.12906

(  0) 0) |

| [85] |

Sun X L, Xu Z H, Xie J Y, et al. Bacillus velezensis stimulates resident rhizosphere Pseudomonas stutzeri for plant health through metabolic interactions[J]. The ISME Journal, 2022, 16(3): 774-787. DOI:10.1038/s41396-021-01125-3

(  0) 0) |

| [86] |

Chen W, Teng Y, Li Z G, et al. Mechanisms by which organic fertilizer and effective microbes mitigate peanut continuous cropping yield constraints in a red soil of South China[J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2018, 128: 23-34. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2018.03.018

(  0) 0) |

| [87] |

Zhang H, Hua Z W, Liang W Z, et al. The prevention of bio-organic fertilizer fermented from cow manure compost by Bacillus sp. XG-1 on watermelon continuous cropping barrier[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2020, 17(16): 5714. DOI:10.3390/ijerph17165714

(  0) 0) |

| [88] |

Wu H S, Yang X N, Zhou X D, et al. Effects of phosphogypsum-containing mixed fertilizer on peanut growth and restoration of soil fertility of continuous monocropping in red soil (In Chinese)[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2013, 50(5): 1006-1012. DOI:10.11766/trxb201211280491 [吴洪生, 杨筱楠, 周晓冬, 等. 磷石膏专用复混肥缓解红壤花生连作障碍效果[J]. 土壤学报, 2013, 50(5): 1006-1012.]

(  0) 0) |

2024, Vol. 61

2024, Vol. 61