2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

3. 中国科学院常熟农业生态实验站, 江苏常熟 215555;

4. 南京大学环境学院, 南京 210023

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

3. Changshu Agro-ecological Experimental Station, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changshu, Jiangsu 215555, China;

4. School of Environment, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China

在我国“高投入、高产出”为特点的集约化农业生产方式下,氮肥的投入量往往超过作物所需,造成氮素的大量盈余,导致农田土壤剖面中存在大量NO3–-N的累积[1-2]。NO3–-N易随水流失造成地下水硝酸盐污染。研究表明,尽管华北平原和太湖地区均是典型的高氮肥投入的农区,氮肥年投入量在400~500 kg·hm−2左右,但两个区域在土壤硝态氮累积特征上存在明显差异,华北平原农田土壤剖面中存在大量硝态氮累积(453~2 155 kg·hm−2)[3],而太湖地区农田土壤剖面中无明显硝态氮累积,0~400 cm土壤剖面NO3–-N的平均含量分别为8.8、31.1和36.4 kg·hm−2[4]。土壤剖面对NO3–-N的消纳作用主要由微生物介导的反硝化过程完成,该过程将NO3–-N逐步还原为N2,使部分氮素通过地下水和土壤孔隙回归大气氮库。研究显示,华北平原小麦-玉米轮作农田0~10 m土壤剖面中,仅在表层(0~20 cm)存在显著的反硝化过程,100 cm以下剖面土壤中反硝化速率较低[5]。然而,目前有关南方农区反硝化的研究多集中在表层土,对剖面土壤的NO3–-N消纳能力还缺乏定量分析,剖面土壤中是否存在反硝化的“热时”和“热区”也不清楚。

剖面反硝化强度受到反硝化微生物群落及底物NO3–-N浓度的控制[6],同时其他环境因素,例如土壤有机质[7]、温度、pH[8-9]、氧气和水分条件,也会通过影响反硝化微生物的群落多样性和丰富度、生物活性和呼吸强度来调控反硝化速率[10-11]。季节气候条件和农作物管理措施的不同也会直接或间接影响反硝化强度[12-13]。可利用性有机碳的缺乏是限制土壤反硝化作用的关键因素[5],华北平原深层土壤剖面中的溶解性有机碳(DOC)仅有10 mg·kg−1,深层土壤中的DOC不足以提供足够的电子供体,导致深层土壤中的反硝化作用受到限制[14],而南方农区剖面反硝化作用是否受到土壤中DOC含量的限制仍不清楚,其关键影响因素仍然未知。

以往采用的土壤反硝化研究方法主要包括乙炔抑制法和15N同位素标记法等,然而,这些方法均存在一定局限性[15-18],无法反映土壤剖面的原位反硝化速率和硝态氮的消纳能力。RoFlow系统(Robotized continuous flow incubation system)采用N2直接测定法[19-20]对原位采集的旱地土柱进行培养,通过实时检测土柱的N2产生量,可以表征旱地土柱原位反硝化速率。而Flow-through培养装置则是采用N2∶Ar比测量法[21],将原位采集的上覆水和土柱共同密闭培养,按一定的时间间隔对上覆水进行采样,利用MIMS(Membrane inlet mass spectrometer)测定溶解在水中N2,表征淹水土柱原位反硝化速率。这两种方法不需要添加底物,培养过程中模拟了原位状态,且适用于淹水和非淹水条件下反硝化速率的测定,对于剖面上处于不同水分状态的土壤都能够进行监测,能够较为直接准确地反映土壤原位反硝化速率,可以用来研究南方农田土壤剖面的反硝化差异。

本研究分别选取江苏省常熟市的水稻-麦轮作农田(稻田)、设施蔬菜地(菜地)和葡萄园(果园)作为研究对象,通过模拟土壤原位条件和监测不同剖面土壤(0~300 cm)在不同季节的反硝化速率,并探究其影响因素,以评估该农区土壤剖面的NO3–-N消纳能力,为南方农区农业面源污染防控与决策提供基础数据支持。

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究区域概况研究区位于江苏省常熟市(31°32’ N,120°41’ E),属于典型的亚热带季风气候,年均温为16 ℃,年降水量为1 055 mm,地下水水位在20~60 cm范围内波动。选取三种当地典型的农业种植模式土壤,分别为水稻—小麦轮作农田、果园和设施蔬菜地。稻麦轮作地位于辛庄镇合泰村,年施氮量约为576 kg·hm−2,稻季从每年的7月开始种植,11月收获,6月中旬施用基肥,7月和8月下旬分别施分蘖肥和穗肥,施肥量分别为120、90和90 kg·hm−2,稻季年施氮量约300 kg·hm−2,麦季从当年11月下旬开始种植,次年6月下旬收获,麦季年施氮量约为276 kg·hm−2,11月中旬施用基肥,次年1月和3月分别施用越冬肥和分蘖肥,施肥量分别为136、80和60 kg·hm−2;大棚设施蔬菜地年施氮量约为600 kg·hm−2,施肥时间分别为10月、12月、2月和5月,每次施肥量约150 kg·hm−2;果园种植葡萄,年施氮量约500 kg·hm−2,3月施用基肥,4月施用促花肥,5月和6月追肥,施肥量分别为240、100、80和80 kg·hm−2。试验样地土壤均为太湖湖基母质发育而来的乌栅土。

1.2 样品采集于2022年10月、11月及2023年2月、3月、5月、7月和9月按照0~20、20~100、100~200和200~300 cm四个层次进行土壤采集。利用单人手持式高频振动原状土壤取样钻机(VD51,澳大利亚)分别采取稻田、菜地和果园的0~300 cm剖面原状土柱。每个采样点设置三个平行。采集的土样一部分用于速率培养,另一部分用于理化性质测定。正式采样开始前30 d分别在稻田、菜地和果园埋设3个地下水采样井,每3天进行一次水样采集,每次连续采集40 d左右,收集好的地下水用作淹水培养的上覆水。

1.3 样品培养及指标测定将稻田、菜地和果园的原状土柱分为0~20、20~100、100~200和200~300 cm四个层次进行培养,由于研究区地下水位常年高于50 cm,所以将果园和菜地的0~20 cm土柱设置为好氧培养组,其余设置为淹水培养组。好氧培养组和淹水培养组均采用鲜土培养。

好氧培养组使用RoFlow系统进行培养并测定反硝化速率。培养过程产生的N2和N2O由检测系统实时检测。培养装置设有16个罐体,每个罐体的出口依次连接至气相色谱仪,装入1 kg原状土柱后进行气体置换,此后16个罐体每3.5 h依次完成一次检测,培养24 h左右,取5次检测的平均浓度(此时罐体内气体浓度趋于稳定),以24 h为培养时间计算N2和N2O的产生速率。

淹水培养组的土壤参考N2∶Ar法[21],使用上述各层混匀的土壤,采用Flow-through培养装置进行培养。将各层混匀的鲜土分别称1 kg装填到底部用橡胶塞密封的培养柱中,加入采集好的原位地下水作为培养用的上覆水,预培养15 h,通过控制进出水管处的止水夹取样,取满水样后,用移液枪加入200 μL 7 mol·L−1 ZnCl2后拧紧瓶盖,分别在0、2、4、6和8 h进行取样,使用MIMS(Bay Instruments,Easton,MD,美国)测定水样中溶解的N2,将该结果与取样时间做线性回归,以斜率作为N2产生速率。

1.4 数据处理剖面各土层硝酸盐去除率(RV)按照以下公式计算:

| $ \text{RV}\left( \% \right) = \frac{{{r_a} \times 365 \times 24 \times M \times {{10}^{ - 6}}}}{{R{e_a} + {r_a} \times 365 \times 24 \times M \times {{10}^{ - 6}} + le \times fe}} \times 100 $ |

式中,ra表示各土层时间尺度上反硝化速率的均值,nmol·g−1·h−1;Rea表示各土层时间尺度上硝态氮残留量的均值,mg·kg−1;M表示N的摩尔质量,g·mol−1;le表示各种植模式下的氮淋溶率,%;fe表示各种植模式下的施氮量,kg·hm−2。其中le参考相关文献选取稻田为7%[22],菜地为19.7%[23],果园为20.5%[24]。由于土壤具有非均质性,采样点和采样时间的不同可能导致土壤理化性质和反硝化速率的异质性,所以在相关性分析前采用Cook距离诊断分析中的异常数据并剔除,采用Spearman相关对土壤理化性质和反硝化速率进行分析,用IBM SPSS Statistics 26软件进行数据分析,利用Origin 2023软件进行制图。

2 结果与讨论 2.1 土壤理化性质时空变化规律三种种植模式下土壤pH在6.2~8.1范围内,总体上呈现中性,表层土壤呈现弱酸性,深层土壤呈现弱碱性。稻季淹水处理使稻田土壤质量含水率(31.6%~42.7%)略高于菜地(25.7%~39.2%)和果园(30.1%~49.9%)。土壤中DOC平均含量为稻田24.2 mg·kg−1、菜地21.5 mg·kg−1、果园22.9 mg·kg−1,在剖面尺度上表现为表层含量最高,除表层外随深度增加逐渐累积的趋势(表 1)。Lan等[25]的研究结果表明,相较于酸性稻田土壤,中性和碱性稻田土壤更有利于反硝化的发生。通常,DOC的缺乏是限制土壤反硝化作用的关键因素[26]。其中Qin等[7]的研究表明,添加富含DOC的液体到土壤中可以显著提高华北平原冬小麦和夏玉米的年度双季轮作地的剖面反硝化作用,在添加三周后,200 cm处剖面中累积的硝酸盐去除了70%。研究表明,华北平原深层土壤的作用受到DOC限制,表层土壤中DOC约40~300 mg·kg−1,深层显著降低到10 mg·kg−1以下[14]。而在本实验中,三种种植模式下的土壤剖面中DOC的含量均相对较高(10.0~86.2 mg·kg−1),可以为反硝化微生物提供充足的碳源和能源,接近中性的pH条件和良好的淹水条件也有利于反硝化,为剖面NO3–-N的消纳作用提供了良好的条件。

|

|

表 1 不同剖面深度土壤理化性质 Table 1 Physical and chemical properties of soil along different profile depths |

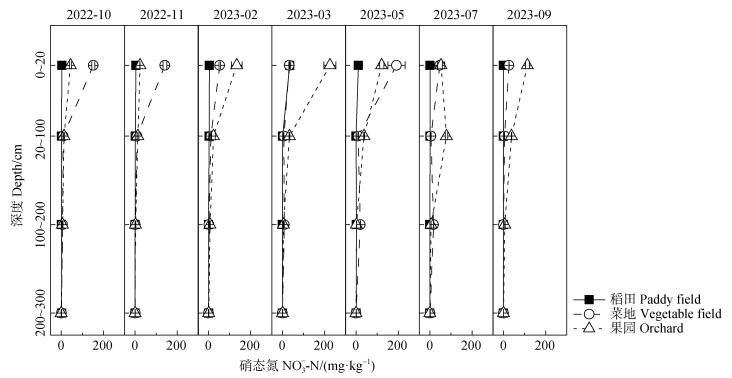

NO3–-N和NH4+-N均呈现出明显的时空异质性。在时间尺度上,果园(9.7~66.0 mg·kg−1)和菜地(7.7~55.8 mg·kg−1)NO3–-N变化较大,而稻田(0.3~9.2 mg·kg−1)变化相对较小。具体来说,从10月到次年9月,果园的NO3–-N呈现先升高再降低的趋势,3月份基肥施用后最高,表土NO3–-N含量为225.2 mg·kg−1。菜地的NO3–-N呈现夏冬低春秋高的趋势,含量最高出现在5月,表土NO3–-N含量为191.8 mg·kg−1。果园7月表土含量相对较低但20~100 cm处含量较高,这是由于对葡萄地多次大量灌水进行催果,导致大量NO3–-N在没有被植物吸收和反硝化作用去除时向下淋溶累积。Huang等[27]的研究结果也表明,葡萄园大量灌水会导致NO3–-N在剖面上的累积层下移,与对照组相比,灌水48 h后累积层由20 cm转变为100 cm。稻田的NO3–-N在3月施用分蘖肥后含量最高,表土含量为34.8 mg·kg−1。总体上,在集中施肥后,土壤表层的NO3–-N含量升高,这一现象在菜地和果园中较为明显。在剖面尺度上,三种种植模式下NO3–-N在表层的含量远大于深层,随着深度增加NO3–-N含量逐渐降低,在100~200 cm处均低于10.0 mg·kg−1,300 cm处几乎没有NO3–-N残留(图 1)。这与太湖农区的研究结果一致[4]。与华北平原的研究结果相比,在同样为高施氮量(大于500 kg·hm−2)的情况下,南方农区的深层剖面累积量(小于2 mg·kg−1)低于华北平原(12~60 mg·kg−1)[14]。

|

图 1 不同种植模式下土壤中硝态氮的剖面(0~300 cm)和季节性变化特征 Fig. 1 Seasonal characteristics of nitrate across soil profile (0~300 cm)among different planting patterns |

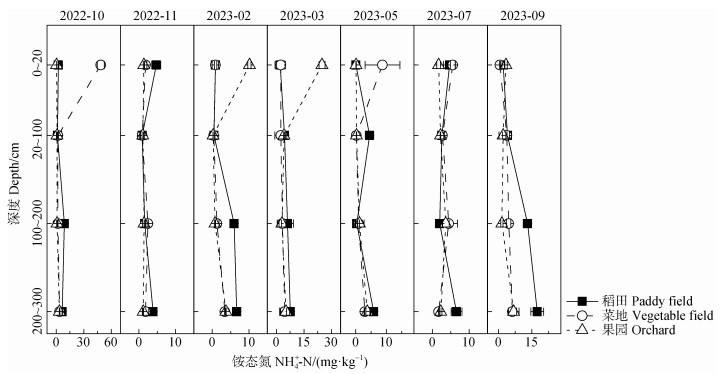

在时间尺度上,菜地和果园的NH4+-N含量变化较大,而稻田变化小。从冬季到次年秋季,三种种植模式下土壤表层变化较大,深层变化较小。菜地和果园NH4+-N表土含量都呈现春秋季高、夏冬季低的特点,菜地10月含量最高,表土含量为48.6 mg·kg−1,果园3月含量最高,表土含量为24.8 mg·kg−1。稻田表土含量最高发生在7月(4.7 mg·kg−1)和11月(4.7 mg·kg−1),分别为稻季和麦季开始进行集中施肥的时间。在空间尺度上,果园和菜地表层含量略高(大于6.0 mg·kg−1),表层以下随深度增加逐渐累积(1.6~3.8 mg·kg−1),稻田则从表层到深层逐渐累积(2.4~7.8 mg·kg−1)。已有研究表明,青藏高原地区表土中的NH4+-N含量为1.76 mg·kg−1 [13],玛纳斯河流域灌区棉田土壤中的NH4+-N约10 mg·kg−1 [28],许祥富等[29]的研究表明,施用尿素可显著增加0~40 cm土壤中NH4+-N的含量,大量施肥后30d内,表层土壤中的NH4+-N含量与对照组相比增加了10倍,这与本实验的研究结果类似。

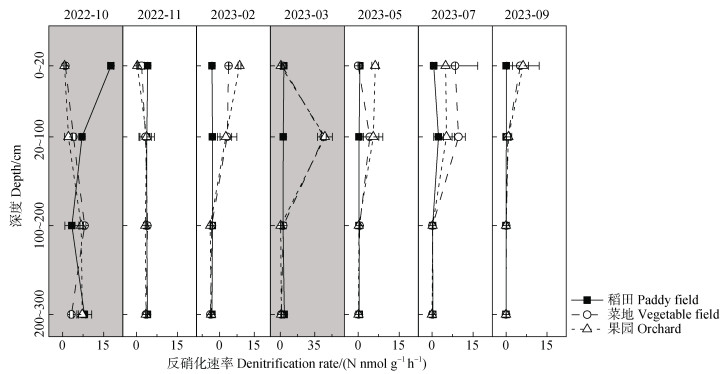

2.2 土壤反硝化速率时空变化规律施肥、灌溉和翻耕等农业管理措施在时间和空间上均会对土壤的理化性质产生影响,反硝化速率受到土壤氧气有效性、温度、湿度和NO3–-N浓度之间相互作用的驱动[30],导致土壤在时间尺度和空间尺度上均可能存在有反硝化作用的“热时”和“热区”[31]。整体上三个种植模式下,菜地反硝化速率(4.3 nmol·g−1·h−1)大于果园(3.9 nmol·g−1·h−1)和稻田(2.1 nmol·g−1·h−1)。

|

图 2 不同种植模式土壤中铵态氮的剖面(0~300 cm)和季节性变化特征 Fig. 2 Seasonal characteristics of ammonium across soil profile (0-300 cm)among different planting patterns |

稻田在10月出现了明显的反硝化“热时”,反硝化速率达到17.6 nmol·g−1·h−1,这一时期处于水稻的拔节孕穗和灌浆施肥期,土壤处于嫌气状态且有大量的外源NO3–-N投入,良好的淹水条件和高浓度反硝化底物有利于反硝化作用。菜地和果园淹水的上层土壤(20~100 cm)在3月时出现了反硝化“热时”,果园(45.3 nmol·g−1·h−1)略高于菜地(44.2 nmol·g−1·h−1),这时处于冬季休闲结束,农民通过大量施肥和灌水进行肥地。此前也有研究表明,蔬菜地在基础施肥后的生长季节开始时和作物氮吸收较低的时期反硝化速率最高,生长季节第一个月的反硝化活性相当于累积季节反硝化的60%~77%[32]。灌溉导致土壤含水量增加从而产生更多的厌氧微位点,进而刺激反硝化活性,Zhang等[33]的研究表明,菜地中的高反硝化中间产物N2O排放率主要是由于频繁施肥和高氮施用或灌溉造成的,总N2O排放量与氮施用率之间存在显著正相关关系(P < 0.01)。

稻田的反硝化“热区”在表土(0~20 cm),平均反硝化速率为3.4 nmol·g−1·h−1,菜地和果园的反硝化“热区”在20~100 cm处,平均反硝化速率分别为11.7 nmol·g−1·h−1和9.4 nmol·g−1·h−1(图 3)。该地区的地下水水位常年在20~60 cm范围内波动,使得稻田表土及菜地和果园的20~100 cm土壤剖面中存在频繁的干湿交替过程,干旱后的再湿润会增加硝酸盐还原基因的丰度并提高硝酸盐还原酶的活性[34],且在干湿交替条件下会促进微生物硝化-反硝化耦合活性提高[35],从而有利于反硝化“热区”的产生。

|

注:灰色背景代表该月存在反硝化作用“热时”。 Note: The grey background represents the hot moments of denitrification. 图 3 不同种植模式土壤反硝化速率随剖面(0~300 cm)的季节性变化特征 Fig. 3 Seasonal characteristics of denitrification rates across soil profile (0-300 cm)among different planting patterns |

稻田反硝化速率(1.1~3.4 nmol·g−1·h−1)在剖面上呈现随深度增加逐渐降低的趋势,菜地(0.6~11.7 nmol·g−1·h−1)和果园(1.0~9.4 nmol·g−1·h−1)均呈现随深度增加先升高再降低的趋势。Yuan等[14]在华北平原的研究结果显示,反硝化在表层土(0~40 cm)中始终最大,并随着土壤深度的增加而降低,年施氮量为600 kg·hm−2处理下,表土反硝化总平均值为2.3 µg·g−1·d−1,0~400 cm反硝化在0.5~3.5 µg·g−1·d−1范围内。太湖农区的研究结果显示,在0~400 cm剖面中,反硝化速率的范围在0.2~1.0 µg·g−1·d−1,且随土壤深度的增加而降低[4]。经换算,本文的研究结果与华北平原反硝化速率相近,但高于太湖农区的研究结果。由于Yuan等[14]有关华北平原的实验结果仅能代表反硝化潜势,存在一定程度高估,南方农区剖面中实际的反硝化速率可能高于华北平原。太湖农区的研究结果[4]采样时间为5月,处在反硝化速率较低的时期,且菜地和果园全部采用淹水培养,导致反硝化“热区”都在表土。

深层土壤中存在NH4+-N的累积现象,但连纲等[36]的研究结果表明NH4+-N在土壤中的淋洗量很小,仅占施肥量的0.008%~0.074%,所以推测深层土壤中可能存在硝酸盐异化还原过程(Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium,DNRA)。研究表明,电子供体(可利用性碳)与受体的比例是反硝化和DNRA之间NO3–-N还原分配的一个重要因素,当电子受体有限时,高的C/NO3–-N比率有利于DNRA过程的发生[37]。本研究中,深层土壤具有较低的NO3–-N、较高的溶解性有机碳,且处于厌氧状态,有利于DNRA过程的发生,因此在深层土壤剖面中可能存在DNRA过程的反应“热区”。

表层土壤NO3–-N含量较高,可能会抑制N2O的还原[38],因此在评估表土反硝化能力时,N2O产生量不应该被忽视。本研究观测了菜地和果园的0~20 cm土层中N2O的排放速率,前五次采样的研究结果表明,N2O在菜地0~20 cm土层中的平均排放速率约0.27 nmol·g−1·h−1,约占N2O和N2总排放量的26.8%;在果园0~20 cm土层中的平均排放速率约0.62 nmol·g−1·h−1,约占N2O和N2总排放的29.0%。上述研究结果表明,菜地和果园0~20 cm土层中N2O的产生也对硝态氮的去除具有一定贡献。研究表明[39],稻田的长期淹水环境会抑制N2O的排放,但干湿交替可能会促进N2O产生,本研究未检测淹水组的N2O产生速率,这可能导致淹水组的反硝化速率存在一定低估。

总体上,反硝化“热时”与农业施肥和灌溉时期一致,此时“热区”的反硝化活性较强,可以在较短时间内去除大量投入的外源氮,降低了淋溶风险。虽然深层土壤中的反硝化速率相对较低,但对淋溶硝态氮的去除量也十分可观。即使在非反硝化“热区”,土壤中仍有0.97~4.38 nmol·g−1·h−1的反硝化速率,能够持续消纳土壤中残留的NO3–-N。

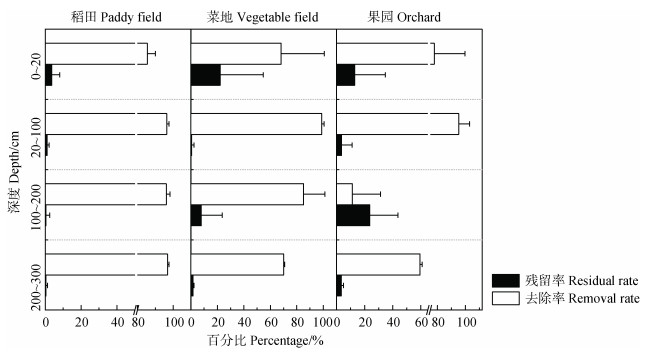

2.3 剖面土壤硝态氮消纳能力及影响因素整体上三个种植模式下,在不考虑植物吸收和径流损失的情况下,稻田土壤的NO3–-N去除率最高,在表土中去除率约85.6%,深层土壤剖面NO3–-N去除率在96%以上,菜地土壤的NO3–-N在表土中去除率约为68.1%,在反硝化“热区”去除率可达到98.8%(图 4)。果园土壤的NO3–-N在表土中去除率为77.9%,在反硝化“热区”去除率可达到95.3%。以目前的施肥量来看,NO3–-N在0~300 cm剖面上几乎能被全部消纳,不会污染地下水,NO3–-N地表径流造成污染风险的可能性比淋溶造成风险的可能性大。相关研究[32]也表明,南方农田稻季总淋洗量仅占施肥量的1.4%~2.8%,麦季地表径流氮损失通常更多,且以NO3–-N为主,占施肥量的38%~67%[40]。河北地区菜地中的氮素损失以NO3–-N为主,据研究数据估算,地表径流损失约占总损失量的86%,且施肥量和径流量越大,氮素损失比率越高[41]。

|

图 4 不同种植模式下土壤剖面硝态氮的去除率 Fig. 4 Nitrate removal percentage across soil profile under different planting patterns |

相关性分析结果表明,剖面NO3–-N含量和反硝化速率呈现显著的正相关关系(r = 0.39,P < 0.001),其他因子和反硝化速率没有相关关系,这表明在本实验中pH、DOC和NH4+-N不是限制剖面反硝化作用的关键因子,NO3–-N含量是限制该地区农田反硝化速率的关键因子。Yuan等[14]的研究表明,高施氮情况下,反硝化在剖面上主要受DOC控制(R2 = 0.79,P < 0.001)。根据Brye等[42]所描述的理想化反硝化反应方程,反硝化消耗的C∶N质量比为12︰14。假设深层土壤中的DOC全部可以被微生物利用,此时深层土壤中的C∶N可以支撑全部NO3–-N被转化,与华北平原不同,南方农田剖面反硝化并不受DOC限制。

3 结论南方农田三种种植模式下土壤剖面均具有较强的反硝化能力,稻田、菜地和果园土壤剖面的年平均反硝化速率分别为2.1 nmol·g−1·h−1、4.3 nmol·g−1·h−1和3.9 nmol·g−1·h−1。三种种植模式下的土壤剖面反硝化速率均存在明显的“热时”和“热区”,其中稻田土壤反硝化“热时”主要发生在10月,“热区”主要发生在0~20 cm处;而菜地和果园反硝化的“热时”主要发生在3月,“热区”主要发生在20~100 cm处。相关性分析结果表明,土壤NO3–-N含量是三种种植模式下剖面土壤反硝化过程的主要限制因子。反硝化过程发生的“热时”和“热区”能有效去除三种种植模式下土壤剖面的硝态氮,三种种植模式下土壤剖面无明显NO3–-N残留。除反硝化过程外,厌氧氨氧化、硝酸根氨化和硝酸根同化也会消耗土壤NO3–-N,未来应关注这些过程对剖面土壤NO3–-N去除的贡献。

致谢 感谢中国科学院南京土壤研究所苗茜同学在样品采集与培养过程中给予的帮助。

| [1] |

Zhou J Y, Gu B J, Schlesinger W H, et al. Significant accumulation of nitrate in Chinese semi-humid croplands[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 25088. DOI:10.1038/srep25088

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Wu H Y, Song X D, Zhao X R, et al. Accumulation of nitrate and dissolved organic nitrogen at depth in a red soil Critical Zone[J]. Geoderma, 2019, 337: 1175-1185. DOI:10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.11.019

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Cui S H, Shi Y L, Groffman P M, et al. Centennial-scale analysis of the creation and fate of reactive nitrogen in China (1910-2010)[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(6): 2052-2057.

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Yan X Y, Zhou W. Groundwater nitrate removal through denitrification under farmland in Yangtze River Delta (In Chinese)[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2019, 56(2): 350-362. DOI:10.11766/trxb201809050445 [颜晓元, 周伟. 长江三角洲农田地下水反硝化对硝酸盐的去除作用[J]. 土壤学报, 2019, 56(2): 350-362.]

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Chen S M, Wang F H, Zhang Y M, et al. Organic carbon availability limiting microbial denitrification in the deep vadose zone[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2018, 20(3): 980-992. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.14027

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Béraud C, Piola F, Gervaix J, et al. Biological denitrification inhibition (BDI)on nine contrasting soils: An unexpected link with the initial soil denitrifying community[J]. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2024, 188: 109188.

(  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Qin S P, Hu C S, Clough T J, et al. Irrigation of DOC-rich liquid promotes potential denitrification rate and decreases N2O/(N2O+N2)product ratio in a 0–2 m soil profile[J]. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2017, 106: 1-8.

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Čuhel J, Šimek M. Proximal and distal control by pH of denitrification rate in a pasture soil[J]. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2011, 141(1/2): 230-233.

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Šimek M, Jı́šová L, Hopkins D W. What is the so-called optimum pH for denitrification in soil?[J]. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2002, 34(9): 1227-1234.

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Li Z L, Tang Z, Song Z P, et al. Variations and controlling factors of soil denitrification rate[J]. Global Change Biology, 2022, 28(6): 2133-2145. DOI:10.1111/gcb.16066

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Wang Y, Hu C S. Research advances on community structure and function of denitrifiers (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture, 2010, 18(6): 1378-1384. [王莹, 胡春胜. 环境中的反硝化微生物种群结构和功能研究进展[J]. 中国生态农业学报, 2010, 18(6): 1378-1384.]

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Hu J, Liao X L, Vardanyan L G, et al. Duration and frequency of drainage and flooding events interactively affect soil biogeochemistry and N flux in subtropical peat soils[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2020, 727: 138740. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138740

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Zhou L L, Liu M J, Li M J, et al. Effects on ammonium nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen in rhizosphere soil of highland barley under different fertilization treatments (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin, 2022, 38(30): 85-90. [周兰兰, 刘梅金, 李明军, 等. 不同施肥处理对青稞根际土壤铵态氮和硝态氮的影响[J]. 中国农学通报, 2022, 38(30): 85-90.]

(  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Yuan H J, Qin S P, Dong W X, et al. Denitrification rate and controlling factors for accumulated nitrate in the deep subsoil of intensive farmlands: A case study in the North China Plain[J]. Pedosphere, 2019, 29(4): 516-526. DOI:10.1016/S1002-0160(17)60472-7

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Murakami T, Kumazawa K. Measurement of denitrification products in soil by the acetylene inhibition method[J]. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 1987, 33(2): 225-234. DOI:10.1080/00380768.1987.10557568

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Xuan Y X, Mai Y W, Xu Y Q, et al. Enhanced microbial nitrification-denitrification processes in a subtropical metropolitan river network[J]. Water Research, 2022, 222: 118857. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2022.118857

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Lin X B, Lu K J, Hardison A K, et al. Membrane inlet mass spectrometry method (REOX/MIMS)to measure 15N-nitrate in isotope-enrichment experiments[J]. Ecological Indicators, 2021, 126: 107639. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107639

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Qin S P, Hu C S, Oenema O. Quantifying the underestimation of soil denitrification potential as determined by the acetylene inhibition method[J]. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2012, 47: 14-17.

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Molstad L, Dörsch P, Bakken L R. Robotized incubation system for monitoring gases (O2, NO, N2O, N2)in denitrifying cultures[J]. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 2007, 71(3): 202-211. DOI:10.1016/j.mimet.2007.08.011

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Qin S P, Clough T, Luo J F, et al. Perturbation-free measurement of in situ di-nitrogen emissions from denitrification in nitrate-rich aquatic ecosystems[J]. Water Research, 2017, 109: 94-101. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.11.035

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Li X B, Xia Y Q, Lang M, et al. N2: Ar technique for direct determination of denitrification rate of aquatic ecosystems using membrane inlet mass spectrometry (In Chinese)[J]. Journal of Agro-Environment Science, 2013, 32(6): 1284-1288. [李晓波, 夏永秋, 郎漫, 等. N2∶Ar法直接测定淹水环境反硝化产物N2的产生速率[J]. 农业环境科学学报, 2013, 32(6): 1284-1288.]

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Tian Y H, Yin B, Yang L Z, et al. Nitrogen runoff and leaching losses during rice-wheat rotations in Taihu Lake region, China[J]. Pedosphere, 2007, 17(4): 445-456. DOI:10.1016/S1002-0160(07)60054-X

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Min J, Zhang H L, Shi W M. Optimizing nitrogen input to reduce nitrate leaching loss in greenhouse vegetable production[J]. Agricultural Water Management, 2012, 111: 53-59. DOI:10.1016/j.agwat.2012.05.003

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Yang G, Wang Y, Wang S Q, et al. Legume cover with optimal nitrogen management and nitrification inhibitor enhanced net ecosystem economic benefits of peach orchard[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2023, 873: 162141. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162141

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Lan T, Han Y, Cai Z C. Denitrification and its product composition in typical Chinese paddy soils[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2015, 51(1): 89-98. DOI:10.1007/s00374-014-0953-4

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

McCarty G W, Bremner J M. Availability of organic carbon for denitrification of nitrate in subsoils[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 1992, 14(3): 219-222. DOI:10.1007/BF00346064

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Huang L B, Levintal E, Erikson C B, et al. Molecular and dual-isotopic profiling of the microbial controls on nitrogen leaching in agricultural soils under managed aquifer recharge[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2023, 57(30): 11084-11095.

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Shi X, Li Y H, Li F D. Variation characteristics and influencing factors of soil ammonium nitrogen and nitrate nitrogen in cotton fields in different irrigation districts of Manas River Basin (In Chinese)[J]. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Sunyatseni, 2021, 60(6): 80-90. [石轩, 李艳红, 李发东. 玛纳斯河流域不同灌区棉田土壤铵态氮和硝态氮变化特征及影响因素[J]. 中山大学学报: 自然科学版, 2021, 60(6): 80-90.]

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Xu X F, Lin Z M, Lin Q H, et al. Effect of different nitrogen fertilizer levels on vertical distribution of NH4+-N and NO3-N in rubber plantation soil (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Tropical Agriculture, 2009, 29(5): 6-11. [许祥富, 林钊沐, 林清火, 等. 施氮量对橡胶园土壤铵态氮和硝态氮垂直分布的影响[J]. 热带农业科学, 2009, 29(5): 6-11.]

(  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Wallenstein M D, Myrold D D, Firestone M, et al. Environmental controls on denitrifying communities and denitrification rates: Insights from molecular methods[J]. Ecological Applications, 2006, 16: 2143-2152. DOI:10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[2143:ECODCA]2.0.CO;2

(  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Anthony T L, Silver W L. Hot spots and hot moments of greenhouse gas emissions in agricultural peatlands[J]. Biogeochemistry, 2024, 167: 461-477.

(  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Qasim W, Zhao Y M, Wan L, et al. The potential importance of soil denitrification as a major N loss pathway in intensive greenhouse vegetable production systems[J]. Plant and Soil, 2022, 471(1): 157-174.

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Zhang J, Li H, Wang Y C, et al. Multiple-year nitrous oxide emissions from a greenhouse vegetable field in China: Effects of nitrogen management[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 616/617: 1139-1148. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.206

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Wu Q Y, Tang Y H, Chen R Y, et al. Metabolism characteristics of nitrogen functional microorganisms in bioretention system under multiple dry-wet alternation[J]. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 2023, 53: 103685. DOI:10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.103685

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Carrasco D, Fernández-Valiente E, Ariosa Y, et al. Measurement of coupled nitrification-denitrification in paddy fields affected by Terrazole, a nitrification inhibitor[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2004, 39(3): 186-192. DOI:10.1007/s00374-003-0673-7

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Lian G, Wang D J, Lin J H, et al. Characteristics of nutrient leaching from paddy field in Taihu Lake area (In Chinese)[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2003, 14(11): 1879-1883. [连纲, 王德建, 林静慧, 等. 太湖地区稻田土壤养分淋洗特征[J]. 应用生态学报, 2003, 14(11): 1879-1883.]

(  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Tiedje J M, Sexstone A J, Myrold D D, et al. Denitrification: Ecological niches, competition and survival[J]. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 1983, 48: 569-583. DOI:10.1007/BF00399542

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Qin S P, Ding K R, Clough T J, et al. Temporal in situ dynamics of N2O reductase activity as affected by nitrogen fertilization and implications for the N2O/(N2O+N2)product ratio and N2O mitigation[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2017, 53(7): 723-727. DOI:10.1007/s00374-017-1232-y

(  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Senbayram M, Wei Z J, Wu D, et al. Inhibitory effect of high nitrate on N2O reduction is offset by long moist spells in heavily N loaded arable soils[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2022, 58(1): 77-90. DOI:10.1007/s00374-021-01612-x

(  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Ma B G, Guan R H, Liu L, et al. Nitrogen loss in vegetable field under the simulated rainfall experiments in Hebei, China[J]. Water, 2021, 13(4): 552. DOI:10.3390/w13040552

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Cao Y S, Sun H F, Liu Y Q, et al. Reducing N losses through surface runoff from rice-wheat rotation by improving fertilizer management[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2017, 24(5): 4841-4850. DOI:10.1007/s11356-016-8191-y

(  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Brye K R, Norman J M, Bundy L G, et al. Nitrogen and carbon leaching in agroecosystems and their role in denitrification potential[J]. Journal of Environmental Quality, 2001, 30(1): 58-70. DOI:10.2134/jeq2001.30158x

(  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 62

2025, Vol. 62