2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

3. 中国科学院地球环境研究所, 西安 710061;

4. 中国科学院南京土壤研究所, 南京 211135;

5. 华中农业大学资源与环境学院, 武汉 430070;

6. 西北农林科技大学资源环境学院, 陕西杨凌 712100

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

3. Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi'an 710061, China;

4. Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 211135, China;

5. College of Resources & Environment, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, China;

6. College of Natural Resources and Environment, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi 712100, China

土壤是地球表层系统中最活跃、最重要的组成部分,支持地球主要生命过程并维持生态系统平衡[1]。土壤健康对保障粮食安全和维持生态系统功能至关重要[2]。长期以来,集约化农业虽提高了粮食生产力,却也加速了土壤退化、养分失衡,导致土壤肥力下降和生态系统功能退化,对土壤健康构成潜在威胁[3]。土壤微生物作为土壤中最具丰富性和多样性的有机生物体,参与土壤有机质分解、养分循环、污染物降解等过程,并与植物生产力及土壤健康息息相关,一直是土壤学、环境学等领域关注的热点和前沿[4]。微生物多样性高的土壤表现出更强的生态功能调控能力,对维持土壤健康和可持续生产至关重要[5]。因此,系统梳理微生物功能与土壤健康之间的关系,并阐明微生物的调控机制,对保障土壤可持续利用有重要意义。

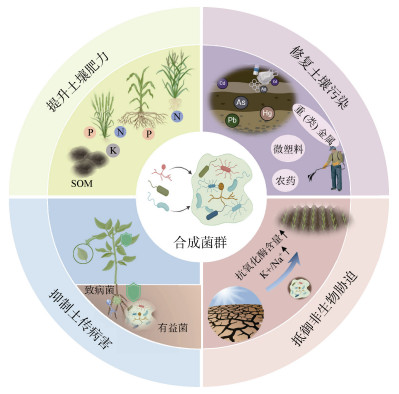

合成菌群是指通过人工设计,将多个已知功能和分类地位明确的微生物菌株在特定条件下按确定比例混合,形成具有高效功能和可控性的简化微生物群落[6]。与单一菌株或天然微生物组相比,基于生态学和合成生物学构建的合成菌群能够更高效地执行复杂任务[7](图 1)。通过选择具有互补功能的微生物并组合构建合成菌群,可增强其功能稳定性和环境适应性。这种群落结构提高了微生物群落的稳定性,简化了难以调控的自然群落,并通过形成新的微环境来促进功能发挥[8]。合成菌群可以通过自身代谢参与污染物降解、调节植物激素水平、增强养分吸收以及提高对非生物胁迫的耐受性,从而促进植物生长和土壤健康[9]。此外,合成菌群也具备深入研究微生物互作模式、解析菌株间营养互惠与功能互补关系、预测微生物群落潜在功能特性的价值[10]。构建与应用具有特定功能的合成菌群,能更加高效、稳定地提升土壤健康,为农业绿色可持续发展提供新思路。本文系统综述了合成菌群的特征、构建方式及其在修复土壤污染、提升土壤肥力、提高作物抗逆性等方面的作用机制与应用,展望了合成菌群在提升土壤功能和健康方面的未来研究方向,以期为保障土壤健康和维持地球生态安全提供重要参考。

|

图 1 合成菌群与土壤健康的关系 Fig. 1 Relationships between synthetic communities and soil health |

土壤生态系统的稳定性并非是单一微生物物种独立作用的结果,而是通过复杂微生物群落之间的相互作用和代谢交流共同实现。这些群落的动态变化对于维持生物地球化学循环及关键功能方面至关重要[11]。土壤微生物群落结构复杂且多变,解析群落间的互作过程与机制对土壤健康的影响一直是土壤学研究的热点和前沿[12]。因此,简化微生物群落并构建稳定且可控的合成菌群,以实现对土壤健康的有效调控,展现出良好的应用前景。合成菌群相较于自然微生物群落和单一菌株具有以下显著优势:(1)合成菌群由已知微生物组成,结构简单且可控,具有重现性;(2)合成菌群通过微生物间交流和功能互补,能够模拟自然微生物群体的复杂性,展现出较单一菌株更强的环境适应性和功能多样性[13];(3)合成菌群中的微生物可以根据不同的代谢途径进行功能分工,优化个体微生物的代谢,从而提高整体群落的代谢效率[14];(4)在实际应用中,合成菌群展现出较强的适应能力,能够更好地应对环境变化[15];(5)由于合成菌群结构相对简单,可以通过数学模型进行描述和构建,从而实现对更复杂系统模型的构建和验证[16]。

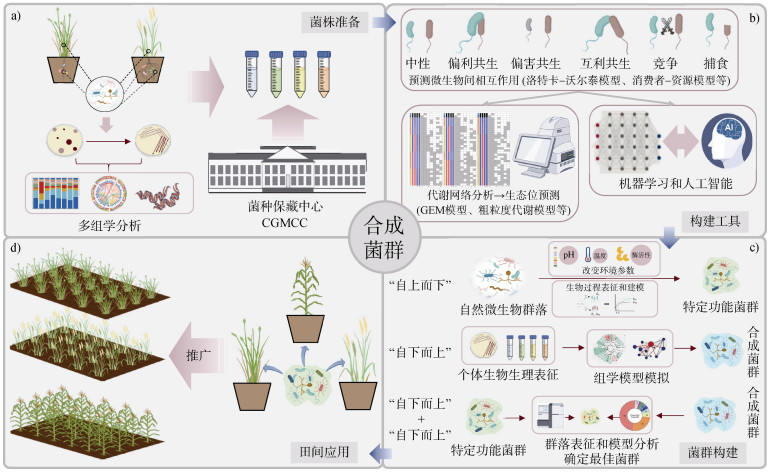

2 合成菌群的构建 2.1 合成菌群的构建原则目前构建合成菌群主要基于以下四项原则[17]:(1)考虑微生物间的相互作用;(2)控制微生物群落的时空分布;(3)确保菌群的鲁棒性和稳定性;(4)制定种群控制策略。该原则已被广泛应用于构建简单有效的合成菌群,但构建功能多样的合成菌群,需依赖更精准的构建策略。例如,针对重金属污染、土传病害以及干旱胁迫等土壤问题,研究者提出了一种基于“生境匹配–功能互补–稳定共存”的合成菌群构建策略[18]。该策略通过分析微生物之间的互作网络,确定菌株的群落稳定性,从而实现微生物群落组成和功能的精确调控与优化(图 2)。尽管这种策略在理论上能够有效调控微生物群落的组成和功能,但在实际应用中仍存在挑战。首先,合成菌群与外界微生物间的相互作用机制尚不完全明确;并且这种复杂的相互作用难以通过外界干预进行有效调整,可能导致群落功能在实际应用中发挥不稳定。因此,如何构建合成菌群,使其能有效发挥各个微生物的功能促进土壤健康,成为关键。

|

图 2 合成菌群的构建与应用 Fig. 2 Construction and application of synthetic communities |

合成菌群构建方法大致分为“自上而下”和“自下而上”两类[6](图 2c)。“自上而下”的构建方法是从生态系统层面出发,通过调整环境参数或物理化学生物过程,模拟微生物群落的自然变化、演替或恢复,经过连续的继代培养,逐步获得结构简化但功能明确的微生物群落[19]。例如,Gilmore等[20]从马粪中富集天然厌氧菌群,通过连续的继代培养促进微生物间共同进化,自上而下地形成高度稳定的高效木质素降解合成菌群。Díaz-García等[21]采用稀释刺激和稀释灭绝的组合策略,获得一个物种数量最少但能有效分解木质素的合成菌群。随着高通量测序、多组学分析和生物信息技术的发展,“自下而上”的设计理念被提出[22],该方法以微生物群落的代谢网络及其产物为核心,使用模型或网络分析明确微生物群落间的互作关系,从分子层面设计并优化特定微生物群落的代谢特征[23]。例如,Zhuang等[24]通过分析不同生长阶段、土壤类型和农业实践中的根际微生物群落,确定与生长/产量参数相关的分类群,并通过差异丰度分析来筛选菌株,构建了促进宿主生长的合成菌群。尽管“自上而下”的方法通过优化物理化学参数实现了目标功能,但该方法忽略了群落的代谢网络和相互作用,效率低且成本高,限制了群落分子层面的优化[25]。同时,由于微生物组工程的工具和原理尚不完善,“自下而上”的构建方法也存在不确定性。

为了提升合成菌群的效率和可控性,近年来研究者提出了结合“自下而上”和“自上而下”两种方法的构建策略[26]。这一方法融合了自然合成菌群和筛选功能菌群,利用过程模型与代谢模型,模拟生态系统的动态变化、物质平衡和代谢物质转化,从而优化菌群构建策略。例如,Xu等[27]利用以除草剂阿特拉津为单一氮源的培养基富集并筛选出具有降解阿特拉津潜力的特定功能微生物群落,而后构建了这些微生物的基因组尺度代谢模型,通过模型预测菌群生长、降解阿特拉津能力和群落间特定的代谢交换通量,确定最佳菌群组合。模拟和实验结果均表明,添加由Halobacillus和Halomonas构建的合成菌群可显著提高阿特拉津的降解效率。Ruan等[28]通过“自上而下”策略施加外部选择压力对初始微生物菌群进行驯化,促使其重新组装并形成具有特定功能的菌群,随后结合“自下而上”策略,利用代谢模型模拟关键微生物组合的代谢活性,预测最佳菌株组合并验证,最终成功构建高效合成菌群。

2.3 合成菌群功能和稳定性的影响因素合成菌群相比单一微生物能够更高效地执行复杂任务[29],但其功能和稳定性在选择、组合到重组过程中受到多种因素影响,可能导致预期功能偏差。研究发现,不同的初始接种比例(如1∶1和1∶1 000)会显著影响合成菌群的物种组成、代谢能力和种间相互作用[30]。因此,在构建过程中需要充分考虑微生物间的相互作用类型(包括中性、偏利共生、偏害共生、互利共生、竞争和寄生或捕食)[31],协调其生长速率,确定接种顺序,并控制各菌株的细胞密度和数量以及评估在此过程中可能导致某些菌株丢失的情况等[32]。此外,土著微生物群落对外源接种菌株影响显著,可能导致其功能失稳[33]、抗性减弱或功能冗余[34]。因此,如何平衡微生物间的代谢活动并控制种群水平是构建稳定菌群的关键挑战。

有研究表明可以通过建立交叉喂养模式和调控群体感应机制协调微生物代谢和控制种群水平[35]。交叉喂养是指自然界中大多数微生物不能合成自身所需的全部营养物质,而通过代谢物交换与邻近微生物实现互补[36]。这种互作可以是单向、双向或多向的,增强了微生物群落的稳定性与功能性[37]。例如,Zuñiga等[32]通过元转录组学、代谢组学和计算模型揭示了条件依赖性代谢物分泌和交叉喂养模式,为准确预测微生物间的生长速率、代谢物交换和基因组含量提供了新的视角。另一种调控机制是群体感应,它是一种细胞间通信机制,微生物通过分泌特定的信号分子(如酰基高丝氨酸内酯、自诱导肽等),根据种群密度来协调群体行为[38]。当信号分子浓度超过阈值时,会与特定细胞受体结合,启动激活或抑制靶基因的表达[39]。群体感应还可以通过自诱导物控制细胞裂解或毒素产生,调节菌群中的个体数量[40]。理解这些机制并选择合适的工具和模型调节微生物群落间的互作,对于构建功能稳定、可控的合成菌群具有重要的理论和技术意义。

2.4 合成菌群的构建工具随着生物信息学和生态学模型的发展,越来越多的工具被用于构建具有特定功能的合成菌群,展示了良好的应用前景。目前,研究者开发了许多基于微生物相互作用的生态模型,如广义的洛特卡-沃尔泰拉模型、消费者-资源模型和粗粒度代谢模型等(表 1),这些模型通过模拟微生物间的资源竞争和代谢途径的交互,为合成菌群的设计提供理论基础。了解每个群落成员的空间分布和生态位是保持群落结构稳定的关键[41]。不同的生态学建模方法,包括基于性状的模型、基于个体的模型以及基因组尺度的代谢网络模型(Genome scale metabolic model,GEM),均可用于生态位预测[42](表 1)。例如,Dhakar等[43]利用GEM模型预测菌株SRS16的特定氨基酸(谷氨酰胺和天冬酰胺)促进了除草剂的降解,实验也证实了这一结果。此外,TbasCO(Trait-based Comparative 'Omics)工具通过识别不同菌株功能性状表达的差异,提高了对生态位分化特征动态变化的预测准确性[44]。

|

|

表 1 合成菌群构建相关模型 Table 1 Synthetic communitiess construction models |

一些创新的计算方法已被用于处理海量基因组学数据,以设计合成菌群[41]。这些工具包括antiSMASH(预测微生物次级代谢产物合成能力)[45]、MacSyFinder(检测大分子系统)[46]和PHI-base(用于致病性鉴定的)[47],它们在识别菌群功能特性和次生代谢产物方面起着重要作用。SuperCC(Super Community Combinations)是一种新型的微生物组建模框架,它强调代谢相互作用在塑造微生物组功能中的作用,不同于现有模型,它能够模拟更复杂的微生物群落协同作用,这种框架为设计天然微生物组提供了指导,并促进了合成菌群的构建[28]。

关键分类群能够引导微生物群落的组装过程和功能表达。识别微生物群落中的关键分类群不仅有助于构建功能稳定的合成菌群,还可以帮助理解微生物群落中的稀有但功能重要的分类群[48]。因此,识别微生物群落中的基于功能性状的功能性核心微生物群落而不是微生物网络分析中的分类核心微生物群落[49],对于合成菌群的构建至关重要。最新研究提出了一种基于深度学习的数据驱动关键物种识别框架,通过学习微生物群落的组装规则,识别高关键度物种,揭示了高关键度物种的群落特异性,展示了机器学习在微生物群落管理中的应用潜力,为复杂微生物群落的数据驱动管理铺平了道路[50]。

此外,人工智能和机器学习技术也逐渐被用于合成菌群的优化。它们可以帮助指导分类群和功能的高维组合空间优化[41]。例如,BacterAI平台可以通过实验生成的数据进行迭代学习,从而优化模型设计合成菌群[51]。然而,由于数据集规模的限制以及缺乏标准化的评价体系,目前仍存在一些挑战。因此,需要进一步发展和完善相关工具和模型,以克服现有挑战,推动合成菌群设计向更高效、更精准的方向发展。

3 合成菌群在土壤健康提升中的应用环境污染和耕地质量退化是威胁土壤健康的重大挑战,近年来,合成菌群作为提升土壤健康的有效策略,受到土壤健康领域研究者们的广泛关注。随着合成生物学的发展,通过引入多样化的生物合成途径构建稳定的合成菌群并将其应用于实际场景,正在为土壤修复提供新机遇[59]。例如,通过设计交叉喂养与合成群体感应电路系统可以促进菌群稳定,有助于微生物成员的共存[35]。此外,材料介导策略也被引入到合成菌群的构建与应用中。例如,微流控装置、生物打印、模具/封装和水凝胶活体材料等技术能够为微生物定制不同生态位,从而提高其生存率和功能稳定性[60]。基因编辑技术的快速发展、第三代基因编辑技术CRISPR-Cas的推出,为合成菌群在土壤修复中的应用研究带来了突破。例如,通过CRISPR技术将关键的环境污染物降解基因导入具有强大适应性和繁殖能力的微生物中,进一步构建出具有特定功能的合成菌群,能够显著提升其对重金属等难降解物质的处理效率[61]。然而,未来还需要进一步考虑基因工程菌对土壤健康和生态环境的影响。同时,跨学科策略在合成菌群的研究领域中展现出巨大潜力。例如,点击化学技术广泛应用于纳米医学、材料科学、生物分子标记/成像领域,而在土壤微生物和植物研究中的应用很少[62]。点击化学的可视化生物分子过程的特性,使其能够在分子水平上清晰揭示土壤–植物–微生物间相互作用机制。未来,点击化学等跨学科技术,可以深化对合成菌群在土壤健康提升中的作用机制的理解。

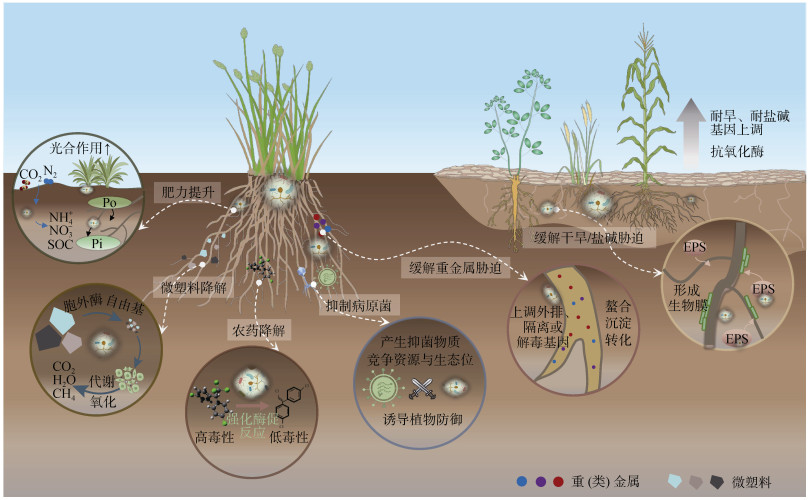

3.1 合成菌群在土壤污染修复中的应用重金属、农药、微塑料等土壤污染物对土壤健康构成了巨大威胁[63]。合成菌群在提高植物重金属抗性和提升土壤健康方面也有着不可替代的作用。Wang等[64]通过共接种根瘤菌和丛枝菌根真菌,发现Proteobacteria、Actinobacteria、Acidobacteria和Chloroflexi作为关键细菌类群,促进了苜蓿根际养分吸收和镉抗性的提高,阐释了根际微生物在外源微生物添加后的变化及作用,证明了多种共生微生物的共接种更有助于植物有效应对镉胁迫。合成菌群也能通过群体感应和水平基因转移协同激活金属抗性机制。例如,暴露于重金属污染时,微生物能通过上调金属外排、隔离或解毒基因抵抗重金属[65]。

合成菌群同样是介导农药降解的有效途径,可以通过微生物间的协同作用提高降解效率。Li等[66]分离出一组对除虫菊酯农药(β-氟氯菊酯)具有高度降解作用的合成菌群,其中肠杆菌在初期参与了β-氟氯菊酯的降解代谢,其他细菌属(Microbacterium、Ochrobactrum、Pseudomonas、Achromobacter)在后期参与了中间代谢物的降解,通过产生羧酸酯酶和氧化还原酶降解β-氟氯菊酯,降低对紫花苜蓿的毒性。此外,利用微生物参与不同酶促反应的特性构建的合成菌群,较单一菌株更有利于农药的完全降解。例如,由真菌(Fomitopsis pinicola)和细菌(Ralstonia pickettii)单独降解双对氯苯基三氯乙烷(Dichloro Diphenyl Trichloroethane,DDT)农药时,降解率分别为42%和31%,而当两种菌协同作用时降解率达到了61%。其中,真菌(F. pinicola)能将DDT转化为细菌(R. pickettii)细胞可利用的产物,而细菌(R. pickettii)能刺激真菌(F. pinicola)菌丝的生长,构成互惠共生的关系。两者共同作用,使DDT最终转化为毒性较低的代谢物1-氯-2, 2-二(4-氯苯基)乙烯[67]。

土壤微生物作为生态系统的分解者,能够有效降解微塑料[68]。微生物通过释放胞外酶和自由基诱导水解或氧化还原反应,将大分子聚合物分解成小分子的产物(例如低聚物、二聚体和单体)并进入微生物细胞,随后被代谢氧化成CO2、H2O和CH4等无机产物,实现微塑料的降解[69]。合成菌群能整合多菌株代谢活性,从而达到高效降解微塑料的目的。一个由弯孢菌、交替孢霉、单纯青霉和镰刀菌组成的合成菌群用于降解聚乙烯,在3个月内使其重量减轻27%,而单个菌株对聚乙烯的降解率很低,仅为0.7%~7.7%[70]。Elsamahy等[71]基于白蚁肠道共生体中分离出的三株酵母菌构建了合成菌群,该菌群能够合成多种低密度聚乙烯(Low-density polyethyleneplastics,LDPE)降解酶(如锰过氧化物酶,漆酶和木质素过氧化物酶),在45天内使LDPE的强度和重量分别下降了63.4%和33.2%。以上结果说明合成菌群将是促进重金属、农药和微塑料等污染物生物降解的有利途径,对维持土壤健康方面至关重要(图 3)。

|

图 3 合成菌群提升土壤健康的作用机制 Fig. 3 Underlying mechanisms of synthetic communities to promote soil health |

土壤微生物驱动碳、氮、磷等元素的循环[72]。在调控土壤固碳方面,合成菌群能通过自身固定碳和微生物介导植物有机碳输入两种主要形式输入碳。Xiao等[73]证实了稻田生态系统中自养微生物组在固定CO2提高有机碳库累积中的关键作用。在植物促生方面,合成菌群能够将不同促生功能的菌株进行组合,强化有机碳的输入。例如,研究发现通过微生物群落的作用,显著提高了长角豆(Ceratonia siliqua L.)的叶绿素和类胡萝卜素含量,提高了水分和营养吸收,从而增强了植物的光合作用[74]。在调控固氮方面,具有固氮能力的植物促生菌群可以通过提高固氮酶活性,从而增加土壤中氮含量[75]。合成菌群能够能通过将元素难利用形式转化为可利用形式,实现土壤养分高效转化利用。在调控磷有效性方面,磷酸盐增溶菌群能够通过酸化、螯合、交换反应和聚合物的形成将不可用的磷(如磷酸钙、磷酸铁和磷酸铝)转化为植物可利用的形式[76],而将有机磷(如植酸、磷脂、核酸等)通过酸性磷酸酶、植酸酶、磷脂酶和其他酶矿化成生物可利用的形式,以促进植物根系对磷的吸收利用[77]。

更多研究发现合成菌群具备协同调节土壤多种养分供应能力。Jiao等[78]发现引入共生固氮体系能够增强氮矿化和磷溶解功能微生物丰度,显著提高了土壤有效氮磷的含量。合成菌群也能通过不同微生物之间的功能协同作用多维度提升土壤肥力。例如,Shen等[79]从植物生长促生菌中分离出具有高氮气固定,磷、钾溶解能力的三种菌株,将其组合应用于猕猴桃生长体系中,结果表明合成菌群的施用能够增加土壤中氮磷钾含量的有效性,并促进猕猴桃的生长。此外,有研究者通过利用原位促生菌构建的合成菌群进行田间实验证明合成菌群显著增强了土壤的细菌群落,有效提高了大部分碳、氮、磷功能基因的丰度和土壤酶活性[80],为合成菌群的实际应用提供了参考。合成菌群与土著微生物在提高养分有效性方面也存在很强的联系。例如,在蓝莓种植体系中,添加由10种细菌组成的合成菌群,改变了土壤中土著根瘤菌群落的组成,增加了植株的茎重和干重,增加了土壤中硝酸盐的含量,提高了植株对氮、钾的吸收[81]。可见,以关键功能微生物为核心构建合成菌群,实现以合成菌群调控土壤养分高效转化利用在土壤健康领域具有很大的的应用前景(图 3)。

3.3 合成菌群在土传病害根际免疫中的应用由土壤传播病原菌引起的作物病害严重威胁着粮食安全和土壤健康[82]。植物根际是植物、病原菌和微生物群落相互作用的关键位点,植物病害的发生与根际微生物群落的群落结构和多样性密切相关[83]。Li等[84]从番茄植株根际分离出6种菌株(包括非致病性细菌和致病性番茄雷氏菌),利用模型表征出促进和拮抗两种相互作用群落,测试这两种群落在病原菌入侵后的表现,发现拮抗型根际细菌群落抑制病原菌入侵,而促进型群落有利于病原菌入侵。因此,通过人为添加合成菌群调控微生物群落功能,构建免疫型根际土壤微生态环境,是提升土壤健康的有效途径。

养分和生态位竞争是合成菌群保护植物免受病原菌侵害的重要机制。例如,Hu等[85]构建了由8株假单胞菌组成的合成菌群,发现在整个实验过程中菌群的高生物多样性使其在根际保持高密度,增加了菌群的生态位宽度和资源竞争能力,从而显著抑制番茄根际青枯病原菌的生长,降低了发病率。同时,大量研究表明合成菌群产生的抑菌物质对病原体的生长具有抑制作用。例如,将内生真菌镰刀菌与枯草芽孢杆菌共培养,与单一菌株培养相比,产生了有抗菌功效的脂态类化合物等,使次生代谢物的积累增加78倍[86]。为保护马铃薯免受根腐病的侵害,研究者从22种抗性菌组合中筛选出由5种效果最好的菌株组合的合成菌群,发现菌群能够产生生物表面活性剂、铁载体和抗生素化合物等抑制病害的发生,使发病率降低了46%[87]。

通过激活宿主对病原体产生系统性抗性抵御病原体入侵也是合成菌群介导抵御病原菌的一种常见方法。Zhou等[88]选择205个菌株构建不同功能的合成菌群,并使用组学方法监测其在抑制番茄根腐病中的作用,发现跨界菌群(细菌和真菌)显著丰富了更多的抗病相关途径,如激活氧化途径以及分泌脱落酸等有机酸。其中,激活氧化途径可诱导植物抗病相关的超敏反应[89],从而抑制病原体增殖,而脱落酸相关途径可通过激活防御基因增强番茄抗病能力[90]。以上研究说明,抑制植物病害是微生物群落共同作用的结果,并且高度多样化的微生物群落与单个微生物分类群相比能更有效抵御病原菌侵害植物。未来,建立可控稳定的微生物相互作用网络,实现微生物群落功能的精确调控,将有助于了解植物-微生物-病原体的关系,预防植物病害的发生(图 3)。

3.4 合成菌群在提高作物抵御非生物胁迫中的应用在非生物胁迫中,干旱被认为是经济作物产量和生产力低下的主要不利因素,造成巨大的经济损失并威胁粮食安全[91]。大量研究表明利用特定的合成菌群可以稳定作物的产量,已成为可持续农业中提高抗旱能力的重要途径。合成菌群能通过分泌胞外多糖(Exopoly Saccharides,EPS)或聚合物形成生物膜,粘附在作物根部。EPS具有较高的保水能力,已被证明在抵御干旱等多种非生物胁迫方面具有坚实的作用[92]。例如,研究者利用能够产生EPS的铜绿假单胞菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa)、粪产碱菌(Alcaligenes faecalis)和变形杆菌(Proteus penneri)处理玉米种子,可提高土壤水分含量和植物生长性状(茎和根的长度、叶面积)以及植物生物量[93]。同时,合成菌群能调节干旱条件下植物酶和抗氧化系统,增强作物抗旱性。Huang等[94]发现,干旱条件下,接种Burkholderia sp.和Mitsuaria sp.的玉米植株表现出生理特性变化,例如抗氧化活性的提高、脯氨酸含量的增加、叶片中植物激素的积累以及丙二醛含量的降低。此外,合成菌群还能够通过触发与植物防御系统相关的各种基因和转录因子的转录重编程来帮助植物抗旱。研究表明,枯草芽孢杆菌GOT9通过诱导多种耐旱基因DREB1D、CSD3和WRKY7以及NCED3、RAB18、RD20和RD29B提高油菜和拟南芥的抗旱性[95]。

盐胁迫通常是由钠离子(Na+)和活性氧的过度积累引起的,它们破坏了植物的生理过程,包括离子稳态、脂质代谢、光合作用和蛋白质合成[96]。近年来,利用合成菌群提高植物对恶劣环境的适应能力,使之适应干旱土壤和盐碱地的生长成为研究热点。在之前的一项研究中发现[97],耐盐细菌对植物病原菌有拮抗作用,几丁质分解细菌可以帮助植物摆脱盐胁迫,两者的协同作用提高了植物对盐碱土壤的抗性。此外,研究表明接种来自干旱或盐碱地区的合成菌群能够帮助植物抵御盐胁迫。Schmitz等[98]研究发现,利用沙漠植物核心根际微生物组构建的合成菌群接种于番茄植株后,植株地上部鲜重显著增加,盐胁迫相关标记基因SOS1、SOS2和WRKY8的表达显著上调且番茄茎部的Na+/K+比值显著降低,有效提升了番茄的抗盐能力。目前,许多研究已经证实,相较于细菌,真菌具有更强的抗干旱和耐盐碱特性。例如,丛枝菌根真菌可以通过增加渗透物浓度来维持植物细胞内的渗透平衡共生,增加了盐渍条件下植株对K+的吸收,降低了对Na+的吸收,保持了较低的Na+/K+比值[99]。所以未来在构建合成菌群协助作物应对干旱和盐胁迫时,可以考虑加入真菌微生物,同时结合菌株调控和数学建模等多维手段,揭示群落动态变化中微生物相互作用模式,解析合成菌群应对胁迫的作用机制,培育抗旱抗盐的优质合成菌群,促进农业的可持续发展(图 3)。

4 总结与展望土壤微生物是土壤功能的主要驱动者,通过构建高效可控的合成菌群,发挥各菌株的特定功能,对维持土壤健康以及地球生态安全具有重要意义。尽管合成菌群在污染土壤修复、土壤肥力提升和增强抗胁迫能力等方面取得了重要进展,但仍面临许多挑战,如合成菌群间微生物互作机制不清楚、菌群构建工具不完备、田间应用不充分等问题。未来研究应重点关注以下几个方面,以推动合成菌群在土壤健康提升中的广泛应用:

1)培育和驯化新型高效功能合成菌群。目前,研究主要集中于高丰度微生物,但许多低丰度稀有微生物往往在土壤健康中发挥关键作用。未来应利用多组学技术、活性探针和代谢标记等方法,分离并培养出对土壤健康有重要贡献的低丰度关键微生物。通过对微生物进行功能定向的筛选和驯化,培育出能够适应不同生境、效果良好且可控的微生物菌株,建立以菌群为最小单位的合成菌群资源库,使其具有普适性。同时,需要深入研究外源微生物与土著微生物的相互作用,以应对外源菌群对土壤核心微生物群落的影响,并评估环境风险。

2)开发新型合成生物学工具构建合成菌群。目前已开发出较多针对微生物间相互作用研究的模型,但是由于难以获得完整的高质量基因组,阻碍了菌株的鉴定和模型的准确应用。因此,未来应该开发出更加精确的基因组测序和代谢物测定等技术,为模型的构建提供准确的数据。例如,CRISPR-Cas等基因组编辑技术,为构建具备特殊功能的合成菌群提供了重要支持。同时,未来可以为合成菌群相关数据集建立数据库,并基于与不同宿主和表型相关的海量合成菌群数据集探索潜在关联,以识别跨实验室的基因型-表型作用机制。此外,未来应针对合成菌群细胞间通讯以及代谢物交流,深入揭示微生物之间相互作用的机制和微生物组的整体功能,进一步提升对微生物相互作用及群落组装机制的认识,推进其在土壤健康领域的实践应用。

3)基于人工智能筛选合成菌群。人工智能(Artificial Intelligence,AI)由于能够处理复杂的数据集,预测微生物行为及其对宿主健康的影响已经在生物医学领域被广泛应用。在土壤微生物领域中,机器学习算法也展现出预测微生物群落组分之间复杂的物理和化学相互作用以及监测微生物群落组成变化的潜力,将其与COMETS网络[100]结合有望筛选最佳功能合成菌群。此外,CAMII系统结合AI和大规模培养技术,已被证明能够介导菌群构建系统的分类形态描述,为靶向筛选合成菌群提供了新的策略[101]。因此,未来可以扩展合成菌群的数据集,并构建人工智能模型,结合选择和基准策略,以挑选适合的机器学习技术进行精确筛选合成菌群。但与此同时,还需特别关注在应用AI技术时涉及的伦理问题,以避免AI践踏人类权利和突破道德原则。

4)构建合成菌群在大田特定生境中的应用策略。在实际应用中,由于大田条件多变且复杂,导致田间实验结果常与实验室结果不一致。为保障合成菌群在大田条件下应用成功,未来需优先建立宿主合成菌群模拟系统,通过调节合成菌群的组装和应用流程,建立适应不同农业生态系统的最佳方法。根据不同的环境压力调节合成菌群的结构和功能,实现靶向应用合成菌群提升土壤健康。随着计算机模型的发展,即时预测土壤微生物动态变化成为可能,未来基于这些模型的应用将极大提升我们应对农业生态系统中挑战的能力,进而推动农业的绿色可持续发展,保障土壤健康和粮食安全。

| [1] |

Lehmann J, Bossio D A, Kögel-Knabner I, et al. The concept and future prospects of soil health[J]. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 2020, 1(10): 544-553.

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Zhu Y G, Peng J J, Wei Z, et al. Linking the soil microbiome to soil health (In Chinese)[J]. Scientia Sinica: Vitae, 2021, 51(1): 1-11. [朱永官, 彭静静, 韦中, 等. 土壤微生物组与土壤健康[J]. 中国科学: 生命科学, 2021, 51(1): 1-11.]

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Jin Q, Wang C, Sardans J, et al. Effect of soil degradation on the carbon concentration and retention of nitrogen and phosphorus across Chinese rice paddy fields[J]. Catena, 2022, 209: 105810.

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Banerjee S, van der Heijden M G A. Soil microbiomes and one health[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2023, 21(1): 6-20.

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Bastida F, Eldridge D J, García C, et al. Soil microbial diversity-biomass relationships are driven by soil carbon content across global biomes[J]. The ISME Journal, 2021, 15(7): 2081-2091.

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Grosskopf T, Soyer O S. Synthetic microbial communities[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2014, 18(100): 72-77.

(  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Burmølle M, Webb J S, Rao D, et al. Enhanced biofilm formation and increased resistance to antimicrobial agents and bacterial invasion are caused by synergistic interactions in multispecies biofilms[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(6): 3916-3923.

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Jin R T, Song J, Liu C, et al. Synthetic microbial communities: Novel strategies to enhance the quality of traditional fermented foods[J]. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2024, 23(4): e13388.

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Wang N, Wang X X, Chen L, et al. Biological roles of soil microbial consortium on promoting safe crop production in heavy metal(loid)contaminated soil: A systematic review[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2024, 912: 168994.

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Liu Y X, Qin Y, Bai Y. Reductionist synthetic community approaches in root microbiome research[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2019, 49: 97-102.

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Hartmann M, Six J. Soil structure and microbiome functions in agroecosystems[J]. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 2023, 4: 4-18.

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Wei Z, Yang T J, Ren P, et al. Advances and perspectives on synthetic microbial community in the study of rhizosphere immunity (In Chinese)[J]. Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University, 2021, 44(4): 597-603. [韦中, 杨天杰, 任鹏, 等. 合成菌群在根际免疫研究中的现状与未来[J]. 南京农业大学学报, 2021, 44(4): 597-603.]

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Biliouris K, Babson D, Schmidt-Dannert C, et al. Stochastic simulations of a synthetic bacteria-yeast ecosystem[J]. BMC Systems Biology, 2012, 6: 58.

(  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Brenner K, You L C, Arnold F H. Engineering microbial consortia: A new frontier in synthetic biology[J]. Trends in Biotechnology, 2008, 26(9): 483-489.

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Jagmann N, Philipp B. Design of synthetic microbial communities for biotechnological production processes[J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2014, 184: 209-218.

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Orphan V J. Methods for unveiling cryptic microbial partnerships in nature[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2009, 12(3): 231-237.

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Johns N I, Blazejewski T, Gomes A L, et al. Principles for designing synthetic microbial communities[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2016, 31: 146-153.

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Jiao S, Yang Y F, Xu Y Q, et al. Balance between community assembly processes mediates species coexistence in agricultural soil microbiomes across Eastern China[J]. The ISME Journal, 2020, 14(1): 202-216.

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Fuhrman J A. Microbial community structure and its functional implications[J]. Nature, 2009, 459(7244): 193-199.

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Gilmore S P, Lankiewicz T S, Wilken S E, et al. Top-down enrichment guides in formation of synthetic microbial consortia for biomass degradation[J]. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2019, 8(9): 2174-2185.

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Díaz-García L, Huang S X, Spröer C, et al. Dilution-to-stimulation/extinction method: A combination enrichment strategy to develop a minimal and versatile lignocellulolytic bacterial consortium[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2021, 87(2): e02427-20.

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Bairey E, Kelsic E D, Kishony R. High-order species interactions shape ecosystem diversity[J]. Nature Communications, 2016, 7: 12285.

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Rotaru A E, Shrestha P M, Liu F H, et al. A new model for electron flow during anaerobic digestion: Direct interspecies electron transfer to Methanosaeta for the reduction of carbon dioxide to methane[J]. Energy & Environmental Science, 2014, 7(1): 408-415.

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Zhuang L B, Li Y, Wang Z S, et al. Synthetic community with six Pseudomonas strains screened from garlic rhizosphere microbiome promotes plant growth[J]. Microbial Biotechnology, 2021, 14(2): 488-502.

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Liu W W, Wu B, Xiang M C, et al. From microbiome to synthetic microbial community (In Chinese)[J]. Microbiology China, 2017, 44(4): 881-889. [刘炜伟, 吴冰, 向梅春, 等. 从微生物组到合成功能菌群[J]. 微生物学通报, 2017, 44(4): 881-889.]

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Lawson C E, Harcombe W R, Hatzenpichler R, et al. Common principles and best practices for engineering microbiomes[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2019, 17(12): 725-741.

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Xu X H, Zarecki R, Medina S, et al. Modeling microbial communities from atrazine contaminated soils promotes the development of biostimulation solutions[J]. The ISME Journal, 2019, 13(2): 494-508.

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Ruan Z P, Chen K, Cao W M, et al. Engineering natural microbiomes toward enhanced bioremediation by microbiome modeling[J]. Nature Communications, 2024, 15(1): 4694.

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Wanapaisan P, Laothamteep N, Vejarano F, et al. Synergistic degradation of pyrene by five culturable bacteria in a mangrove sediment-derived bacterial consortium[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2018, 342: 561-570.

(  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Gao C H, Cao H, Cai P, et al. The initial inoculation ratio regulates bacterial coculture interactions and metabolic capacity[J]. The ISME Journal, 2021, 15(1): 29-40.

(  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Song H, Ding M Z, Jia X Q, et al. Synthetic microbial consortia: From systematic analysis to construction and applications[J]. Chemical Society Reviews, 2014, 43(20): 6954-6981.

(  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Zuñiga C, Li C T, Yu G, et al. Environmental stimuli drive a transition from cooperation to competition in synthetic phototrophic communities[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2019, 4(12): 2184-2191.

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Lourenço K S, Suleiman A K A, Pijl A, et al. Resilience of the resident soil microbiome to organic and inorganic amendment disturbances and to temporary bacterial invasion[J]. Microbiome, 2018, 6(1): 142.

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Allison S D, Martiny J B H. Colloquium paper: Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(Suppl 1): 11512-11519.

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Jiang Y J, Wu R F, Zhang W M, et al. Construction of stable microbial consortia for effective biochemical synthesis[J]. Trends in Biotechnology, 2023, 41(11): 1430-1441.

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Zengler K, Zaramela L S. The social network of microorganisms - how auxotrophies shape complex communities[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2018, 16(6): 383-390.

(  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Pande S, Merker H, Bohl K, et al. Fitness and stability of obligate cross-feeding interactions that emerge upon gene loss in bacteria[J]. The ISME Journal, 2014, 8(5): 953-962.

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Yadav S, Tripathi S, Purchase D, et al. Development of a biofilm-forming bacterial consortium and quorum sensing molecules for the degradation of lignin- containing organic pollutants[J]. Environmental Research, 2023, 226: 115618.

(  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Thaden J T, Lory S, Gardner T S. Quorum-sensing regulation of a copper toxicity system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2010, 192(10): 2557-2568.

(  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Omar Din M, Danino T, Prindle A, et al. Synchronized cycles of bacterial lysis for in vivo delivery[J]. Nature, 2016, 536(7614): 81-85.

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Jing J Y, Garbeva P, Raaijmakers J M, et al. Strategies for tailoring functional microbial synthetic communities[J]. The ISME Journal, 2024, 18(1): wrae049.

(  0) 0) |

| [42] |

van den Berg N I, Machado D, Santos S, et al. Ecological modelling approaches for predicting emergent properties in microbial communities[J]. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2022, 6(7): 855-865.

(  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Dhakar K, Zarecki R, van Bommel D, et al. Strategies for enhancing in vitro degradation of linuron by Variovorax sp. strain SRS 16 under the guidance of metabolic modeling[J]. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2021, 9: 602464.

(  0) 0) |

| [44] |

McDaniel E A, van Steenbrugge J J M, Noguera D R, et al. TbasCO: Trait-based comparative 'omics identifies ecosystem-level and niche-differentiating adaptations of an engineered microbiome[J]. ISME Communications, 2022, 2(1): 111.

(  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Blin K, Shaw S, Augustijn H E, et al. antiSMASH 7.0: New and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2023, 51(W1): W46-W50.

(  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Néron B, Denise R, Coluzzi C, et al. MacSyFinder v2: Improved modelling and search engine to identify molecular systems in genomes[J]. Peer Community Journal, 2023, 3: e28.

(  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Urban M, Cuzick A, Seager J, et al. PHI-base in 2022: A multi-species phenotype database for pathogen-host interactions[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2022, 50(D1): D837-D847.

(  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Hol W H, de Boer W, de Hollander M, et al. Context dependency and saturating effects of loss of rare soil microbes on plant productivity[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2015, 6: 485.

(  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Lemanceau P, Blouin M, Muller D, et al. Let the core microbiota be functional[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2017, 22(7): 583-595.

(  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Wang X W, Sun Z, Jia H J, et al. Identifying keystone species in microbial communities using deep learning[J]. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2024, 8(1): 22-31.

(  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Dama A C, Kim K S, Leyva D M, et al. BacterAI maps microbial metabolism without prior knowledge[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2023, 8(6): 1018-1025.

(  0) 0) |

| [52] |

Zuñiga C, Zaramela L, Zengler K. Elucidation of complexity and prediction of interactions in microbial communities[J]. Microbial Biotechnology, 2017, 10(6): 1500-1522.

(  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Ravikrishnan A, Blank L M, Srivastava S, et al. Investigating metabolic interactions in a microbial co-culture through integrated modelling and experiments[J]. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 2020, 18: 1249-1258.

(  0) 0) |

| [54] |

Kim S, Thapa I, Zhang L, et al. A novel graph theoretical approach for modeling microbiomes and inferring microbial ecological relationships[J]. BMC Genomics, 2019, 20(Suppl 11): 945.

(  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Coyte K Z, Schluter J, Foster K R. The ecology of the microbiome: Networks, competition, and stability[J]. Science, 2015, 350(6261): 663-666.

(  0) 0) |

| [56] |

Niehaus L, Boland I, Liu M H, et al. Microbial coexistence through chemical-mediated interactions[J]. Nature Communications, 2019, 10(1): 2052.

(  0) 0) |

| [57] |

Liao C, Wang T, Maslov S, et al. Modeling microbial cross-feeding at intermediate scale portrays community dynamics and species coexistence[J]. PLoS Computational Biology, 2020, 16(8): e1008135.

(  0) 0) |

| [58] |

Wang L J, Wang X Y, Wu H, et al. Metabolic modeling of synthetic microbial communities for bioremediation[J]. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2023, 53(24): 2092-2111.

(  0) 0) |

| [59] |

Tanouchi Y, Smith R P, You L C. Engineering microbial systems to explore ecological and evolutionary dynamics[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2012, 23(5): 791-797.

(  0) 0) |

| [60] |

Gao H, Jiang W K, Zhang W M, et al. Customized spatial niches for synthetic microbial consortia[J]. Trends in Biotechnology, 2023, 41(12): 1463-1466.

(  0) 0) |

| [61] |

Sharma P, Sirohi R, Tong Y W, et al. Metal and metal(loids)removal efficiency using genetically engineered microbes: Applications and challenges[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021, 416: 125855.

(  0) 0) |

| [62] |

Chen M M, Kopittke P M, Zhao F J, et al. Applications and opportunities of click chemistry in plant science[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2024, 29(2): 167-178.

(  0) 0) |

| [63] |

Li M, Hu J, Wei Z, et al. Synthetic microbial communities: Sandbox and blueprint for soil health enhancement[J]. iMeta, 2024, 3(1): e172.

(  0) 0) |

| [64] |

Wang X, Fang L C, Beiyuan J Z, et al. Improvement of alfalfa resistance against Cd stress through rhizobia and arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi co-inoculation in Cd-contaminated soil[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2021, 277: 116758.

(  0) 0) |

| [65] |

Swift S, Downie J A, Whitehead N A, et al. Quorum sensing as a population-density-dependent determinant of bacterial physiology[J]. Advances in Microbial Physiology, 2001, 45: 199-270.

(  0) 0) |

| [66] |

Li H Y, Ma Y C, Yao T, et al. Biodegradation pathway and detoxification of β-cyfluthrin by the bacterial consortium and its bacterial community structure[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2022, 70(25): 7626-7635.

(  0) 0) |

| [67] |

Purnomo A S, Sariwati A, Kamei I. Synergistic interaction of a consortium of the brown-rot fungus Fomitopsis pinicola and the bacterium Ralstonia pickettii for DDT biodegradation[J]. Heliyon, 2020, 6(6): e04027.

(  0) 0) |

| [68] |

Huang W, Xia X H. Element cycling with micro(nano)plastics[J]. Science, 2024, 385(6712): 933-935.

(  0) 0) |

| [69] |

Sánchez C. Fungal potential for the degradation of petroleum-based polymers: An overview of macro- and microplastics biodegradation[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2020, 40: 107501.

(  0) 0) |

| [70] |

Sowmya H V, Ramalingappa B, Nayanashree G, et al. Polyethylene degradation by fungal consortium[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research, 2015, 9: 823-830.

(  0) 0) |

| [71] |

Elsamahy T, Sun J Z, Elsilk S E, et al. Biodegradation of low-density polyethylene plastic waste by a constructed tri-culture yeast consortium from wood- feeding termite: Degradation mechanism and pathway[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023, 448: 130944.

(  0) 0) |

| [72] |

Chu H Y, Ma Y Y, Yang T, et al. The strategies for development of the subdiscipline of soil biology for the 14th Five-Year Plan (In Chinese)[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2020, 57(5): 1105-1116. DOI:10.11766/trxb202006150298 [褚海燕, 马玉颖, 杨腾, 等. "十四五" 土壤生物学分支学科发展战略[J]. 土壤学报, 2020, 57(5): 1105-1116.]

(  0) 0) |

| [73] |

Xiao K Q, Ge T D, Wu X H, et al. Metagenomic and 14C tracing evidence for autotrophic microbial CO2 fixation in paddy soils[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2021, 23(2): 924-933.

(  0) 0) |

| [74] |

Boutasknit A, Baslam M, Ait-El-Mokhtar M, et al. Assemblage of indigenous arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and green waste compost enhance drought stress tolerance in carob(Ceratonia siliqua L.)trees[J]. Scientific Reports, 2021, 11(1): 22835.

(  0) 0) |

| [75] |

Wang J J, Li R C, Zhang H, et al. Beneficial bacteria activate nutrients and promote wheat growth under conditions of reduced fertilizer application[J]. BMC Microbiology, 2020, 20(1): 38.

(  0) 0) |

| [76] |

Emami-Karvani Z, Chitsaz-Esfahani Z. Phosphorus solubilization: Mechanisms, recent advancement and future challenge[M]//Soil Microbiomes for Sustainable Agriculture. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

(  0) 0) |

| [77] |

Rizvi A, Ahmed B, Khan M S, et al. Psychrophilic bacterial phosphate-biofertilizers: A novel extremophile for sustainable crop production under cold environment[J]. Microorganisms, 2021, 9(12): 2451.

(  0) 0) |

| [78] |

Jiao S, Chen W M, Wang J L, et al. Soil microbiomes with distinct assemblies through vertical soil profiles drive the cycling of multiple nutrients in reforested ecosystems[J]. Microbiome, 2018, 6(1): 146.

(  0) 0) |

| [79] |

Shen H, He X H, Liu Y Q, et al. A complex inoculant of N2-fixing, P- and K-solubilizing bacteria from a purple soil improves the growth of kiwifruit(Actinidia chinensis)plantlets[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 841.

(  0) 0) |

| [80] |

Hao X W, Gu Y Z, Zhang H Z, et al. Synthetic microbial community promotes bacterial communities leading to soil multifunctionality in desertified land[J]. Microorganisms, 2024, 12(6): 1117.

(  0) 0) |

| [81] |

Schoebitz M, López M D, Serrí H, et al. Combined application of microbial consortium and humic substances to improve the growth performance of blueberry seedlings[J]. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 2016, 16(4): 1010-1023.

(  0) 0) |

| [82] |

Huang X Q, Cai Z C. Soil microbes and control of soil-borne diseases (In Chinese)[J]. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2017, 32(6): 593-600. [黄新琦, 蔡祖聪. 土壤微生物与作物土传病害控制[J]. 中国科学院院刊, 2017, 32(6): 593-600.]

(  0) 0) |

| [83] |

Zhalnina K, Louie K B, Hao Z, et al. Dynamic root exudate chemistry and microbial substrate preferences drive patterns in rhizosphere microbial community assembly[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2018, 3: 470-480.

(  0) 0) |

| [84] |

Li M, Wei Z, Wang J N, et al. Facilitation promotes invasions in plant-associated microbial communities[J]. Ecology Letters, 2019, 22(1): 149-158.

(  0) 0) |

| [85] |

Hu J, Wei Z, Friman V P, et al. Probiotic diversity enhances rhizosphere microbiome function and plant disease suppression[J]. mBio, 2016, 7(6): e01790-16.

(  0) 0) |

| [86] |

Ola A R B, Thomy D, Lai D W, et al. Inducing secondary metabolite production by the endophytic fungus Fusarium tricinctum through coculture with Bacillus subtilis[J]. Journal of Natural Products, 2013, 76(11): 2094-2099.

(  0) 0) |

| [87] |

Krzyzanowska D M, Maciag T, Siwinska J, et al. Compatible mixture of bacterial antagonists developed to protect potato tubers from soft rot caused by Pectobacterium spp. and Dickeya spp[J]. Plant Disease, 2019, 103(6): 1374-1382.

(  0) 0) |

| [88] |

Zhou X, Wang J T, Liu F, et al. Cross-Kingdom synthetic microbiota supports tomato suppression of Fusarium wilt disease[J]. Nature Communications, 2022, 13(1): 7890.

(  0) 0) |

| [89] |

Zhang J, Coaker G, Zhou J M, et al. Plant immune mechanisms: From reductionistic to holistic points of view[J]. Molecular Plant, 2020, 13(10): 1358-1378.

(  0) 0) |

| [90] |

Cheng H Y, Wang Y, Tao X, et al. Genomic profiling of exogenous abscisic acid-responsive microRNAs in tomato(Solanum lycopersicum)[J]. BMC Genomics, 2016, 17: 423.

(  0) 0) |

| [91] |

Vinocur B, Altman A. Recent advances in engineering plant tolerance to abiotic stress: Achievements and limitations[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2005, 16(2): 123-132.

(  0) 0) |

| [92] |

Morcillo R J L, Manzanera M. The effects of plant-associated bacterial exopolysaccharides on plant abiotic stress tolerance[J]. Metabolites, 2021, 11(6): 337.

(  0) 0) |

| [93] |

Naseem H, Bano A. Role of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and their exopolysaccharide in drought tolerance of maize[J]. Journal of Plant Interactions, 2014, 9(1): 689-701.

(  0) 0) |

| [94] |

Huang X F, Zhou D M, Lapsansky E R, et al. Mitsuaria sp. and Burkholderia sp. from Arabidopsis rhizosphere enhance drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana and maize(Zea mays L.)[J]. Plant and Soil, 2017, 419(1): 523-539.

(  0) 0) |

| [95] |

Woo O G, Kim H, Kim J S, et al. Bacillus subtilis strain GOT9 confers enhanced tolerance to drought and salt stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica campestris[J]. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 2020, 148: 359-367.

(  0) 0) |

| [96] |

Zhang W X, Zhi W J, Qiao H, et al. H2O2-dependent oxidation of the transcription factor GmNTL1 promotes salt tolerance in soybean[J]. The Plant Cell, 2023, 36(1): 112-135.

(  0) 0) |

| [97] |

Yang Y Q, Guo Y. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms mediating plant salt-stress responses[J]. New Phytologist, 2018, 217(2): 523-539.

(  0) 0) |

| [98] |

Schmitz L, Yan Z C, Schneijderberg M, et al. Synthetic bacterial community derived from a desert rhizosphere confers salt stress resilience to tomato in the presence of a soil microbiome[J]. The ISME Journal, 2022, 16(8): 1907-1920.

(  0) 0) |

| [99] |

Evelin H, Devi T S, Gupta S, et al. Mitigation of salinity stress in plants by arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: Current understanding and new challenges[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2019, 10: 470.

(  0) 0) |

| [100] |

Dukovski I, Bajić D, Chacón J M, et al. A metabolic modeling platform for the computation of microbial ecosystems in time and space(COMETS)[J]. Nature Protocols, 2021, 16(11): 5030-5082.

(  0) 0) |

| [101] |

Selma-Royo M, Segata N, Ricci L. Human microbiome cultivation expands with AI[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2023, 41(10): 1389-1391.

(  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 62

2025, Vol. 62