2. 中国地质大学(北京)土地科学技术学院, 北京100083;

3. 青岛市国土资源和房屋管理局崂山国土资源分局, 山东青岛 266000

土壤理化分析能有效地还原古人类活动类型及强度,无论是在单个遗址还是区域考古研究中均能提供许多信息,因为土壤是人类活动的舞台,不仅记录了人造景观信息,也保留了社会文化信息。因此土壤理化分析在考古研究中由来已久,20世纪60年代起,在食物残渣、遗物遗迹研究中经常被运用[1]。80年代以来,遗址土壤数据能有效帮助考古学家了解遗物遗迹的年代[2]。进入2000年后,随着土壤理化分析技术的进步,土壤学与考古学的融合得到进一步发展,越来越多的学者开始系统研究土壤理化分析在考古研究中的规范和价值,特别是运用在古人类遗址不同功能区的甄别中[3-5]。

目前,主要研究方法主要为土壤化学性质分析,其中磷、氮、碳使用频率最多,该方法能有效区分出古人类农业区和居住区[6-16]。其他金属元素以及微量元素的运用日渐频繁,特别是微量元素,能更为细致地区分不同古人类活动遗迹以及活动,如制陶、冶炼等[17-23]。磁化率可有效检测出古人类用火迹象[24-25]。此外,土壤微形态在解读古人类具体活动内容,如建筑材料和食物等[26-30]。仰韶村遗址是仰韶文化命名地,是重要的新石器时期遗址,目前已通过多次考古挖掘,确认了地基、饮食、瓮棺、陶窑不同功能区。因此,本研究在该遗址内分别采集不同功能区和未受到古人类活动干扰的土壤剖面(简称自然剖面)土样,分析不同功能区土壤理化性质,并与自然剖面数据进行比较,获知古人类不同活动对土壤的影响程度,并为探究新石器时期古人类活动内容提供土壤学依据。

1 材料与方法遗址概况和自然剖面描述可详见《古人类活动对土壤发育的影响——以河南仰韶村文化遗址为例》一文[31],不同功能区地基、饮食、瓮棺、陶窑如图 1所示。自然剖面在观察深度4 m范围内,间隔10 cm从下至上连续采集土样10 g,不同功能区则在明显特征区位采集土样10 g和土壤微形态样品。色度参数红度(a*)、黄度(b*)、亮度(L*)分析采用日本柯尼卡美能达公司CM-700d分光测色仪测定,磁化率分析采用英国BartingtonMS-2型双频磁化率仪测定,颗粒组成采用英国Mastersizer2000型激光粒度仪测定,游离铁采用CBD法提取测定,矿质全量分析采用碳酸锂-硼酸熔融,X射线荧光光谱分析法测定。土壤微形态样品用不饱和聚酯树脂——丙酮溶液浸渍,再进行切片、磨片,使用Nikon偏光显微镜进行土壤微形态观察。自然剖面各理化性质的400个数据进行平均计算,获得自然背景值[32],以便与不同功能区土壤数据进行对比研究。

|

图 1 古人类遗址不同功能区(1.地基,2.饮食,3.瓮棺,4.陶窑) Fig. 1 Functional areas of the ancient human relic site (1. Housing foundation, 2. Diet, 3. Urn coffin, 4. Pottery kiln) |

色度结果如表 1所示,古人类遗址不同功能区a*范围为1.95~4.76,平均值为3.08;b*范围为4.14~11.84,平均值为8.35;L*范围为14.64~34.94,平均值为25.91。自然剖面a*平均值为5.39,b*平均值为12.59,L*平均值为26.69。

|

|

表 1 土样色度值 Table 1 Chromaticity of the soil samples |

磁化率结果如表 2所示,古人类不同功能区低频磁化率(χlf)范围为124. 6~712. 7×10–8 m3·kg–1,平均值为326.0×10–8 m3·kg–1;频率磁化率(χfd)范围为4.64%~11.37%,平均值为7.96%。自然剖面χlf平均值为132.1×10–8 m3·kg–1,χfd平均值为10.36%。

|

|

表 2 土样磁化率值 Table 2 Magnetic susceptibility of the soil samples |

颗粒组成结果如表 3所示,古人类遗址不同功能区黏粒含量范围为41.5~127.0 g· kg–1,平均含量为89.4 g· kg–1;细粉砂含量范围为255.5~506.0 g· kg–1,平均含量为390.6 g· kg–1;粗粉砂含量范围为284.0~461.0 g· kg–1,平均含量为354.5 g· kg–1;砂粒含量范围为38.0~316.0 g· kg–1,平均含量为170.0 g· kg–1。自然剖面黏粒平均含量为119.7 g· kg–1,细粉砂平均含量为440.9 g·kg–1,粗粉砂平均含量为357.9 g· kg–1,砂粒平均含量为81.5 g· kg–1。

|

|

表 3 土样颗粒组成 Table 3 Particle size composition of the soil samples/(g· kg–1) |

游离铁和游离度结果如表 4所示,古人类遗址不同功能区游离铁范围为2.13~18.84 g·kg–1,平均值为8.97 g·kg–1;游离度范围为8.37%~29.73%,平均值为16.65%。自然剖面游离铁平均值为12.71 g·kg–1,游离度平均值为25.54%。

|

|

表 4 土样游离铁和游离度 Table 4 Free iron and ionization degree of the soil samples |

矿质全量结果如表 5所示,古人类遗址不同功能区SiO2含量范围为656.10~672.80 g·kg–1,平均含量为660.00 g·kg–1;Al2O3含量范围为110.70~157.70 g·kg–1,平均含量为132.7 g·kg–1;Fe2O3含量范围为41.40~60.60 g·kg–1,平均含量为50.30 g·kg–1;CaO含量范围为6.10~24.80 g·kg–1,平均含量为15.50 g·kg–1;P含量范围为5.48~9.98 g·kg–1,平均含量为8.42 g·kg–1。自然剖面SiO2平均含量为670.08 g·kg–1,Al2O3平均含量为143.91 g·kg–1,Fe2O3平均含量为54.04 g·kg–1,CaO平均含量为8.94 g·kg–1,P平均含量为0.67 g·kg–1。

|

|

表 5 土样矿质全量 Table 5 Total mineral content of the soil samples /(g·kg–1) |

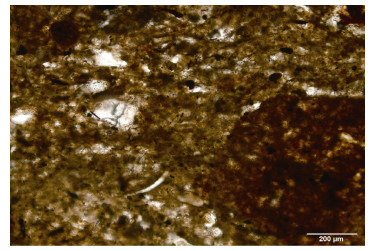

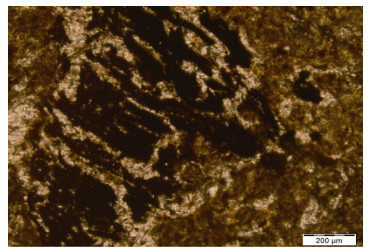

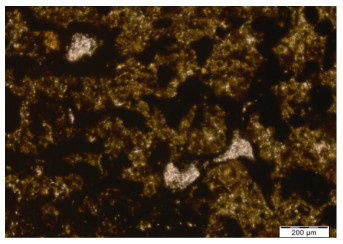

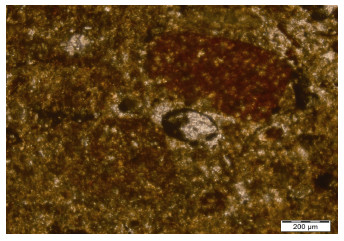

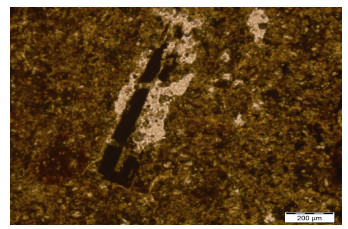

土壤微形态照片均为100倍单偏光下拍摄,地基处土壤微形态中发现贝壳、植物残体,如图 2和图 3所示。饮食处土壤微形态照片显示炭屑含量十分丰富,混在土壤颗粒中,呈一定方向排列或海绵状分布,如图 4和图 5所示。陶窑处土壤微形态显示部分黏土因高温烧制变红,形成氧化铁等赘生物,如图 6所示。部分石英和黏土矿物玻璃化,经煅烧的细小陶器碎片垒结具有较高的双折射率,如图 7所示。

|

图 2 贝壳 Fig. 2 Shell |

|

图 3 植物残体 Fig. 3 Plant residue |

|

图 4 定向分布碳屑 Fig. 4 Directional carbon distribution |

|

图 5 海绵状分布碳屑 Fig. 5 Spongy distribution of carbon dust |

|

图 6 氧化铁 Fig. 6 Ferric oxide |

|

图 7 陶片 Fig. 7 Pottery sherd |

色度方面,古人类不同功能区与自然剖面的a*、b*平均值比值均小于1,L*除地基区和瓮棺区大于1外,其余均小于1。可以看出,古人类活动明显减小了色度数值,以地基、饮食表现明显,但不同活动对土壤颜色改变差异明显,其中地基L*增加,表明增加了碳酸钙类物质。

磁化率方面,除地基区外,饮食区、瓮棺区和陶窑区与自然剖面的χlf的平均值比值均大于1,除瓮棺区外,地基区、饮食区和陶窑区与自然剖面的χfd的平均值比值均小于1。可以看出,古人类活动总体提高了土壤的χlf,以古人类用火形成的饮食、陶窑遗迹表现明显,降低了土壤的χfd,阻碍了土壤发育,瓮棺区除外。

颗粒组成方面,地基区与自然剖面的黏粒、细粉砂、砂粒平均含量比值大于1,饮食区与自然剖面的粗粉砂、砂粒平均含量比值大于1,瓮棺区与自然剖面的细粉砂平均含量比值大于1,陶窑区与自然剖面的砂粒平均含量比值大于3。可以看出,古人类活动增加了粗砂含量,但不同活动差异明显,地基区细粉砂相对增加较多,饮食区粗粉砂、砂粒增加明显,陶窑区砂粒含量增加明显,瓮棺区细粉砂有所增加。

游离铁方面,除瓮棺区外,地基区、饮食区和陶窑区与自然剖面的游离铁和游离度平均值比值均小于1。可以看出,古人类活动减少了游离铁和游离度,阻碍了土壤发育,其中地基区表现明显,瓮棺区游离铁和游离度增加,促进土壤发育。

矿质全量方面,古人类不同功能区与自然剖面的各氧化物和元素平均含量比值中,P大于12,CaO、MnO、Ni、Cu、Zn、Ba大于1,其余均略小于1。可以看出,地基区和饮食区P和CaO含量明显增加,瓮棺区P含量明显增加,Al2O3、Fe2O3含量相对增加,陶窑区P含量也增加。

综上所述,在地基区,古人类利用石灰面覆盖地表,其a*、b*较小、L*较大,χlf和χfd均较小,游离铁为最小值,游离度较小,黏粒含量最高,这可能是古人类利用黏土与石灰岩制作石灰面[33]。CaO含量较高,P含量最高,土壤微形态显示了古人类在石灰面中加入多种不同的集料,如蜗牛等,这也反映了该地区容易获得的矿物[34]。在饮食区,a*、b*、L*均为最小值,χlf较大,χfd为最小值,游离铁和游离度均较小,粗粉砂含量最高。CaO含量最高,P含量较高,土壤微形态显示炭屑含量丰富,表明古人类长期在此利用植物燃烧,烹煮食物,不仅产生了大量磁性物质,导致磁化率值异常高,也产生了大量粗颗粒物质,或是为了及时灭火,人为添加粗砂类物质。通过微形态观察,该处碳屑部分呈现定向排列,表明经过人为清理,古人类可能将过多的灰烬进行清扫。在瓮棺区,根据现场观察,该处属于“瓦片葬”类,即打碎一件或多件陶器平铺或垫于人骨之上。其a*、b*、L*均为最大值,χlf较小,χfd为最大值,游离铁和游离度均为最大值,细粉砂含量最高。Al2O3和Fe2O3含量达到最高,SiO2和CaO含量最小,P含量较高。表明该处土壤发育状况良好,但L*值较高,说明碳酸钙含量丰富,这与其他土壤指标所反映的发育良好相矛盾,推测古人类进行瓮棺埋葬时,人为添加碳酸钙类物质。在陶窑区,a*、b*较大,L*较小,χlf最大,χfd最小,游离铁较小,游离度最小,砂粒含量最高,P含量较高。仰韶时期陶窑的烧制温度可达到950℃~1050℃[35],土壤微形态也显示经过高温煅烧,高温导致了土壤磁化率值出现最大值,并且仰韶时期陶器的烧制环境主要为氧化,土壤中的铁质也大部分转换成Fe3+,从而a*、b*较大。燃烧产物富含P,推测古人类将生活垃圾进行燃烧。

4 结论不同古人类活动对土壤理化性质产生不同的影响,反映了不同的活动内容。地基区内,古人类有目的地选择富含黏土和碳酸钙的石灰面铺设地表,并在石灰面中加入多种不同的集料,如蜗牛壳等,长期居住其上,富集大量含磷物质。饮食区内,古人类用火导致磁化率值升高,并产生或人为添加大量粗颗粒物质,土壤微形态表明古人类在此进行清理,以便长期使用。瓮棺区内,翁棺尸体在腐烂过程中,由于土壤动物和微生物的参与,不仅增加土壤细颗粒,还促进了土壤发育,但碳酸钙含量异常较高,推测人为添加。陶窑区内,古人类高强度用火,导致土壤磁化率值出现最大值,同时氧化烧制环境导致土壤中的铁质物质大部分转化成Fe3+。此外,推测古人类烧制陶器时将生活垃圾进行燃烧,因此P富集。

| [1] |

Pollard A M, Batt C, Kravchenko Y S, et al. Analytical chemistry in archaeology . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Pastor A, Gallello G, Cervera M L, et al. Mineral soil composition interfacing archaeology and chemistry . Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2016, 78(78): 48-59.

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Haslam R, Tibbett M. Sampling and analyzing metals in soils for archaeological prospection:A critique . Geoarchaeology, 2004, 19(8): 731-751. DOI:10.1002/gea.20022

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

MacPhail R I. Soils and archaeology//Encyclopedia of Archaeology. NewYork: Academic Press, 2008.

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Walkington H. Soil science applications in archaeological contexts:A review of key challenges . Earth-Science Reviews, 2010, 103(3/4): 122-134.

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

董广辉, 夏正楷, 刘德成, 等. 文明起源时期河南孟津地区人类活动对土壤化学性质的影响. 兰州大学学报(自然科学版), 2007, 43(1): 6-10. Dong G H, Xia Z K, Liu D C, et al. The impact of human activities on the chemical properties of paleosol in Mengjin, Henan Province during civilization (In Chinese). Journal of Lanzhou University(Natural Science), 2007, 43(1): 6-10. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0455-2059.2007.01.002 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

查理思, 吴克宁, 鞠兵, 等. 二里头文化遗址区土壤化学成分含量及变化研究. 土壤通报, 2013, 44(6): 1414-1417. Zha L S, Wu K N, Ju B, et al. Research on the chemical constituents'contents and changes of Paleosol in Erlitou Culture Sites (In Chinese). Chinese Journal of Soil Science, 2013, 44(6): 1414-1417. (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Salisbury R B. Interpolating geochemical patterning of activity zones at Late Neolithic and Early Copper Age settlements in eastern Hungary . Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40(2): 926-934.

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Nielsen N H, Kristiansen S M. Identifying ancient manuring:Traditional phosphatevs. multi-element analysis of archaeological soil . Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 42(1): 390-398.

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Ferro-Vázquez C, Martínez-Cortizas A, Nóvoa-Muñoz J C, et al. 1500 years of soil use reconstructed from the chemical properties of a terraced soil sequence . Quaternary International, 2014, 346(12): 28-40.

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Homburg J A, Sandor J A. Anthropogenic effects on soil quality of ancient agricultural systems of the American Southwest . Catena, 2011, 85(2): 144-154. DOI:10.1016/j.catena.2010.08.005

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Schlezinger D R, Howes B L. Organic phosphorus and elemental ratios as indicators of prehistoric human occupation . Journal of Archaeological Science, 2000, 27(6): 479-492. DOI:10.1006/jasc.1999.0464

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Fernández F G, Terry R E, Inomata T, et al. An ethnoarchaeological study of chemical residues in the floors and soils of Q'eqchi' Maya houses at Las Pozas, Guatemala . Geoarchaeology, 2002, 17(6): 487-519. DOI:10.1002/gea.10026

(  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Suleimanov R R, Obydennova G T. Soil-archaeological studies of the bronze-age settlement on the Urshak River floodplain, Bashkortostan . Eurasian Soil Science, 2006, 39(8): 820-825. DOI:10.1134/S1064229306080035

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Wilson C A, Davidson D A, Cresser M S. Multi-element soil analysis: An assessment of its potential as an aid to archaeological interpretation . Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35(2): 412-424. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2007.04.006

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Migliavacca M, Pizzeghello D, Ertani A, et al. Chemical analyses of archaeological sediments identified the ancient activity areas of an Iron age building at Rotzo (Vicenza, Italy) . Quaternary International, 2013, 289: 101-112. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.07.016

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

李中轩, 朱诚, 王然, 等. 湖北辽瓦店遗址地层中多元素指标对古人类活动的记录. 海洋地质与第四纪地质, 2008, 28(6): 113-118. Li Z X, Zhu C, Wang R, et al. Multi-element records of the deposits for ancient human activities at the Liaowadian site in Hubei Province (In Chinese). Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 2008, 28(6): 113-118. (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Dirix K, Muchez P, Degryse P, et al. Multi-element soil prospection aiding geophysical and archaeological survey on an archaeological site in suburban Sagalassos (SW-Turkey) . Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40(7): 2961-2970. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2013.02.033

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Cook S R, Clarke A S, Fulford M G, et al. Characterizing the use of urban space:A geochemical case study from Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester, Hampshire, UK) Insula IX during the late first/early second century AD . Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 50(1): 108-116.

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Fleisher J, Sulas F. Deciphering public spaces in urban contexts:Geophysical survey, multi-element soil analysis, and artifact distributions at the 15th-16th- century AD Swahili settlement of Songo Mnara, tanzania . Journal of Archaeological Science, 2015, 55: 55-70. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2014.12.020

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Kamenov G D, Brenner M, Tucker J L. Anthropogenic versus natural control on trace element and Sr-Nd-Pb isotope stratigraphy in peat sediments of southeast Florida (USA) 1500 AD to present . Geochimicaet Cosmochimica Acta, 2009, 73(12): 3549-3567. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2009.03.017

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Zgłobicki W. Impact of microtopography on the geochemistry of soils within archaeological sites in SE Poland . Environmental Earth Sciences, 2013, 70(7): 3085-3092. DOI:10.1007/s12665-013-2368-1

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Gallello G, Pastor A, Diez A, et al. Anthropogenic units fingerprinted by REE in archaeological stratigraphy: Mas d'Is (Spain) case . Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40(2): 799-809. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2012.10.005

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

张岩, 郭正堂, 邓成龙, 等. 周口店第1地点用火的磁化率和色度证据. 科学通报, 2014, 59(8): 679-686. Zhang Y, Guo Z T, Deng C L, et al. The use of fire at Zhoukoudian: Evidence from magnetic susceptibility and color measurements (In Chinese). Chinese Science Bulletin, 2014, 59(8): 679-686. (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

史威, 朱诚, 徐伟峰, 等. 重庆中坝遗址剖面磁化率异常与人类活动的关系. 地理学报, 2007, 62(3): 257-267. Shi W, Zhu C, Xu W F, et al. Relationship between abnormal phenomena of magnetic susceptibility curves of profiles and human activities at Zhongba site in Chongqing (In Chinese). Acta Geographica Sinica, 2007, 62(3): 257-267. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0375-5444.2007.03.003 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Suarez Villagran X, Gianotti C. Earthen mound formation in the Uruguayan lowlands (South America): Micromorphological analyses of the Pago Lindo archaeological complex . Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40(2): 1093-1107. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2012.10.006

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Mallol C, Mentzer S M. Contacts Under the Lens: Perspectives on the role of microstratigraphy in archaeological research . Archaeological & Anthropological Sciences, 2017, 9(8): 1645-1669.

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

庞奖励, 黄春长, 查小春, 等. 关中地区两种不同农业管理方式下土壤微形态特征. 中国农业科学, 2007, 40(11): 2518-2526. Pang J L, Huang C C, Zha X C, et al. Comparison of micromorphological features of two agricultural cultivated soils in Guanzhong areas of Shaanxi Province (In Chinese). Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2007, 40(11): 2518-2526. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0578-1752.2007.11.017 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

张玉柱, 黄春长, 庞奖励, 等. 青海民和官亭盆地喇家遗址古耕作土壤层微形态研究. 土壤学报, 2015, 52(5): 1002-1013. Zhang Y Z, Huang C C, Pang J L, et al. Micromorphology of ancient plow layer of paleosol in the lajia ruins in the Guanting basin, Minhe County, Qinghai Province (In Chinese). Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2015, 52(5): 1002-1013. (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

申朝瑞, 庞奖励, 黄春长. 泾河中游古耕作土壤的微形态特征研究. 中国沙漠, 2007, 27(2): 273-277. Shen Z R, Pang J L, Huang C C. Micromorphological features of palaeo cultivated soil in middle reaches of Jinghe River (In Chinese). Journal of Desert Research, 2007, 27(2): 273-277. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-694X.2007.02.018 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

查理思, 吴克宁, 冯力威, 等. 古人类活动对土壤发育的影响--以河南仰韶村遗址为例. 土壤学报, 2016, 53(4): 850-859. Zha L S, Wu K N, Feng L W, et al. Influence of ancient human activities on development of soil-A case study of Yangshao Village Cultural Relic Site, Henan Province (In Chinese). Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2016, 53(4): 850-859. (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

查理思.仰韶村遗址土壤的特征和功能及古环境研究.北京: 中国地质大学(北京), 2017. Zha L S. Soil characteristics, function and paleoenvironment in Yangshao cultural relic site. Beijing: China University of Geosciences, 2017. (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Branda F, Luciani G, Costantini A, et al. Interpretation of the thermogravimetric curves of ancient pozzolanic concretes . Archaeometry, 2001, 43(4): 447-453. DOI:10.1111/1475-4754.00027

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Casadio F, Chiari G, Simon S. Evaluation of binder/ aggregate ratios in archaeological lime mortars with carbonate aggregate: A comparative assessment of chemical, mechanical and microscopic approaches . Archaeometry, 2005, 47(4): 671-689. DOI:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2005.00226.x

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

周仁, 张福康, 郑永圃. 我国黄河流域新石器时代和殷周时代制陶工艺的科学总结. 考古学报, 1964(1): 1-27. Zhou R, Zhang F K, Zheng Y P. Studies on the technology of Neolithic and Yin and Chou pottery unearthed in the Yellow River valley (In Chinese). Acta Archaeologica Sinica, 1964(1): 1-27. (  0) 0) |

2. School of Land Science and Technology, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China;

3. Laoshan Land Resources Sub-bureau, Qingdao Municipal Land Resources & Housing Administrative Bureau, Qingdao, Shandong 266000, China

2020, Vol. 57

2020, Vol. 57