2. 江苏省固体有机废弃物资源化高新技术研究重点实验室, 作物免疫重点实验室, 国家有机类肥料工程技术研究中心, 南京农业大学资源与环境科学学院, 南京 210095;

3. 西南大学资源环境学院, 重庆 400715;

4. 蚌埠学院土木与水利水电工程学院, 安徽蚌埠 233030

2. Jiangsu Provincial Key Lab of Organic Solid Waste Utilization, Key Laboratory of Plant Immunity, National Engineering Research Center for Organic-based Fertilizers, College of Resources and Environmental Science Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing 210095, China;

3. College of Resources and Environment, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China;

4. Center of Environment Science Experiment of College of Material Science and Chemical Engineering, Bengbu University, Bengbu, Anhui 233030, China

青枯病(bacterial wilt disease)是世界上最具破坏性的植物细菌性土传病害之一,分布于全球各大洲;其致病菌茄科劳尔氏菌(Ralstonia solanacearum,简称青枯菌)的多样性高、寄主范围广(可侵染45科200多种植物),严重威胁全世界的农业生产[1-3]。我国青枯病危害尤为严重,广泛分布于30多个省份和地区,危害近百种植物[4]。青枯菌主要从土壤中侵染作物根系,其在土壤中生存能力强,且土壤中青枯菌的数量与植物青枯病发病率呈显著正相关[4]。因此,明确青枯菌土壤存活的关键影响因素将有助于制定针对性的抑制病害对策。

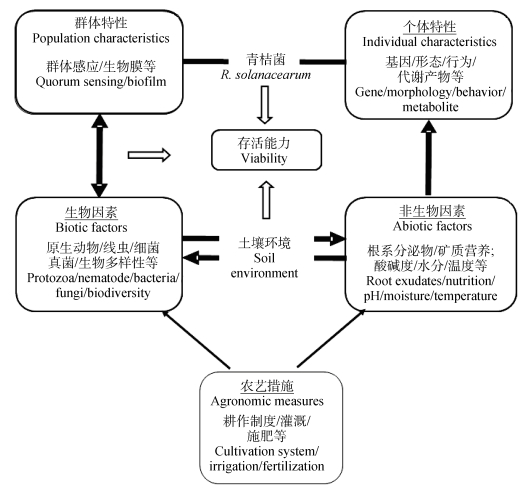

当前青枯菌土壤存活影响因素研究主要面临两个难点:第一,病菌的土壤存活时间长、存活形式多样(包括寄主存在时的土体存活、向寄主根表方向运动迁移时根际存活以及入侵寄主根系时的根表存活);第二,影响病菌土壤存活的因素多元且繁杂,如其自身特性(如基因、行为和代谢产物等)、土壤原生动物、细菌、真菌和噬菌体等生物因素,以及根系分泌物、矿质元素等非生物因素[5-9]。前人试验研究大多仅关注某单一因素对青枯菌土壤存活的影响,缺乏对青枯菌土壤存活影响因素的系统分析。为此,本文通过对国内外青枯菌土壤存活影响因素有关研究报道的系统梳理,从青枯菌自身特性、土壤生物环境和非生物环境三个方面概述青枯菌土壤存活的影响因素(图 1),并对今后青枯菌土壤存活影响因素的研究方向进行思考,以期为阐明青枯菌的土壤存活规律和土传青枯病的系统阻控等提供帮助。

|

图 1 青枯菌土壤存活的主要影响因素及其相互作用 Fig. 1 Key factor influencing the survival of Ralstonia solanacearum in soil and their interactions |

青枯菌基因组一般由染色体和大质粒组成,其染色体上携带着众多维持DNA复制、修复、转录和翻译等必需的看家基因(house keeping genes),大质粒上除一些重要看家基因的副本外,还携带众多菌株特异性基因(strain-specific genes),如编码芳香族化合物分解代谢、铜-锌-镉等重金属抗性的基因簇[10-11]。基因组规模代谢网络模型的预测和试验结果表明,青枯菌可通过表型转换系统(phc)介导依赖于种群密度变化的群体感应系统,动态调控其在土壤中的存活及对寄主植物的侵染[9, 12]。种群密度低时,青枯菌通过启动光谱代谢策略降解利用果胶、半乳糖醛酸酯、木质素和羟基肉桂酸类化合物等,使其可在土壤中长期存活[13]。Ahmad等[14]研究表明青枯菌hppD、hrpG以及oxyR等基因可控制黑褐色色素的产生,以应对环境的氧化胁迫。Brown等[15]研究表明编码resistance nodulation-cell division(RND)家族多药外排泵的acrAB基因是青枯菌应对抗生素、植物抗毒素和洗涤剂等有毒化合物胁迫的重要因子。此外,还有一些基因可能会影响青枯菌在低温环境下的生存能力。例如,Stevens等[16]发现敲除17.6 kb基因岛PGI-1,青枯菌菌株KZR-5对低温的耐受能力更强。

1.2 青枯菌行为对其土壤存活的影响青枯菌在根际定殖和入侵寄主根系时,会发生移动、趋化、存活状态转变、群体感应和生物膜形成等行为,从而趋利避害、提高存活率和增强致病性[6, 17-18]。Tans-Kersten等[17]发现青枯菌的移动能力可帮助其在寄主植物生长发育早期形成入侵。而当无寄主存在时,具有移动能力的青枯菌可更好地摄取营养物质,避免不利环境,甚至迁移到更适宜的寄主上,从而使种群得以更好地扩散和传播[7]。除了移动能力外,趋化反应也是青枯菌提高土壤存活力的重要手段[18]。Yao和Allen[18]发现,与水稻根系分泌物相比,青枯菌更容易被番茄的根系分泌物吸引,青枯菌的这种趋化反应有利于其找到较有利的生存环境。此外,当青枯菌在土壤中遭遇低温和重金属胁迫等时,会迅速转变自身的存活状态进入休眠(viable but nonculturable state,VBNC),以进行自我保护[6]。群体感应系统是一种广泛保守的细菌细胞间交流机制,细菌个体可从群体行为中获得生存和持久的竞争优势[19]。当根际青枯菌种群增加到一定密度时,其群体感应系统开始发挥作用——水平调节青枯菌细胞间的定殖及众多毒力相关基因的表达[19],可有效提高青枯菌在根际的定殖和侵染的成功率。青枯菌还可大量分泌黏稠状胞外多糖类物质包裹青枯菌细胞、细胞残渣、蛋白质、DNA及DNA降解酶等形成生物膜,以抵御各种环境胁迫(如干旱、抑菌物质),进而提高土壤存活率[20]。青枯菌也可分泌胞外DNA降解酶(extracellular DNase,exDNases)参与生物膜形成,破坏植物根系防御反应,帮助青枯菌在土壤存活、根际附着及定殖[21]。Yao和Allen[22]还发现趋氧性运动可显著影响青枯菌生物膜形成,在青枯菌土壤存活、根际定殖过程起重要作用。

1.3 青枯菌代谢产物对其土壤存活的影响青枯菌在土壤中向寄主根系方向迁移过程中产生的代谢产物对维持自身生存、种内和种间交流或/和毒性均十分重要。研究表明,青枯菌能产生Ralfuranone、Yersinabactin和Micacocidin等不同化学结构的铁载体,其中Micacocidin有一定的金属螯合性,在体外具有抗霉菌作用,可增强其在土壤中的竞争能力[23]。青枯菌产生的代谢产物还可协助其进行跨种交流,如Ralsolamycin可诱导34种真菌保守形态的分化,促进土壤真菌形成厚垣孢子[9]。厚垣孢子的形成为青枯菌定殖提供特定的生态位,促进其入侵真菌菌丝,进而提高青枯菌在土壤不良环境中的存活率[7]。此外,青枯菌在向寄主方向迁移过程中可通过群体感应系统产生Ralfuranones代谢物,缺乏Ralfuranone代谢物的突变体,其在细胞间隙中的生长能力显著降低、消失毒力[23]。

2 土壤生物因子对青枯菌存活的影响 2.1 土壤线虫和原生动物的影响青枯菌在土壤中的存活会受到土壤微型动物的影响。根结线虫能破坏寄主根部组织,提高青枯菌根际侵染的成功率,如Furusawa等[24]发现青枯菌和根结线虫在根际的共同侵染会加重番茄青枯病害。原生动物作为土壤食物网中的消费者,能通过捕食作用直接影响青枯菌[25]。Xiong等[26]发现在整个植物生长周期中,田间土壤原生生物和青枯菌的种群动态变化紧密相关;健康植物和发病植物的苗期根际土壤原生动物数量存在显著差异;原生动物与青枯菌的相对丰度呈显著负相关。马超等[27]将青枯菌接入土壤后,发现其在第56天的存活数量与初始土壤鞭毛虫和变形虫的总数成反比,从而说明原生动物的捕食作用抑制了外来青枯菌的活动。这可能是由于原生动物捕食迫使土壤微生物产生了抑菌性物质,从而间接抑制了病原青枯菌[28]。

2.2 土壤细菌和真菌的影响土壤细菌和真菌对青枯菌土壤存活的影响主要是通过资源竞争、拮抗抑制和产生抑菌分泌物等实现的。例如,解淀粉芽孢杆菌可通过竞争根系分泌物降低根际青枯菌的种群密度和致病性[29];黄杆菌可通过降低与青枯菌凝集素结合的糖供应,从而抑制寄主存在状况下土体中的青枯菌[30];荧光假单胞菌产生的挥发性有机物(volatile organic compounds,VOCs)会抑制寄主存在时土体土中青枯菌的生长,抑制率可达32%[31];黄曲霉产生的VOCs对共培养环境中青枯病菌的生长抑制作用较之无菌对照可提升4倍[32]。

除了上述种群水平的研究,前人还探究了土著菌(如细菌、真菌)物种多样性、物种组成、物种间关联度以及土著菌-青枯菌之间生态位重叠度等生物群落特征对青枯菌土壤存活的影响[33-35]。土壤细菌群落的物种多样性与病原青枯菌的入侵存活之间呈负相关关系[36-37]。究其原因或为以下两点:一是根际土著微生物群落代谢较快,留给入侵者资源有限[36];二是与根际微生物群落中的资源利用连接度高、嵌套度低以及土著菌-青枯菌生态位重叠度高等有关[33]。Hu等[34]研究发现接种至根际的有益假单胞菌的基因型越多样,根际青枯菌的密度就越低。Li等[35]通过群落物种间相互作用关系对青枯菌入侵作用的影响研究发现,物种之间呈促进关系的根际菌群会促进青枯菌入侵,而呈拮抗关系的则会抑制青枯菌入侵。

2.3 土壤青枯菌专性噬菌体的影响噬菌体是一类在土壤中普遍存在、专性侵染细菌的病毒,可通过对病原菌的精准裂解,压制病原菌的数量[38]。研究表明,温室条件下裂解型噬菌体可通过阻断青枯菌表面多糖(致病因子之一)的形成,减少病害发生[39]。Murugaiyan等[40]发现,将丝状噬菌体PE204与病菌同时施用后,丝状噬菌体PE226可感染根际中的青枯菌,降低寄主植物的发病率。噬菌体还可通过适应性权衡来抑制土壤中青枯菌的生长,这些权衡可由表达不同毒力因子的高成本以及控制代谢、毒性途径和网络的全局调控基因驱动[9, 41]。例如,噬菌体驱动青枯菌产生噬菌体抗性的同时,也增加了抑制生长等适应性成本;此外,增加专性噬菌体的丰富度也可显著抑制根际青枯菌的丰度,且其抑制作用也间接改变了土著菌群的组成和多样性,使得高度拮抗青枯菌的细菌类群增加[42]。土壤中噬菌体侵染使青枯菌对生防细菌产生的拮抗物质更加敏感,削弱了青枯菌在根际环境的竞争能力,进而有效降低了根际土壤青枯菌的数量[43]。然而,土壤非青枯菌专性噬菌体是否会对青枯菌土壤存活产生影响尚有待进一步研究。

3 土壤非生物因子对青枯菌存活的影响 3.1 根系分泌物的影响根系分泌物对青枯菌在土壤中的存活既可为积极的促进作用,也可为强烈的抑制作用[33, 44-45]。一方面,根系分泌物可为青枯菌提供各种赖以生存的资源,从而促进青枯菌的生长。Wei等[33]发现,根际分泌物的构成会影响土壤微生物群落内部结构及其与病原青枯菌之间的相互作用,进而影响青枯菌的根际定殖。Yang等[45-46]通过微系统试验,分别探讨了根系分泌的资源数量(有效资源含量)和质量(化学计量特性,如碳磷比C/P)对外来青枯菌存活的影响,结果发现有效资源含量越高、C/P越大,青枯菌的存活率越高。Li等[47]的研究发现根系分泌物中的肉豆蔻酸、肉桂酸和反丁烯二酸可有效促进青枯菌定殖在烟草根际。除上述直接作用外,根系分泌物还可通过影响青枯菌与土著微生物之间的相互作用从而调控病菌的存活。Gu等[48]发现青枯菌感染过的番茄根系分泌物(咖啡酸)可减少共生根际微生物群落多样性,对青枯菌的土壤存活产生积极影响。另一方面,当植物的根系分泌物中富含杀菌物质,则能直接杀害土壤中的青枯菌。例如,孔雀草可通过根系分泌大量噻吩类物质,能抑制青枯菌的存活数量[49]。植物种属的差异也会影响根系分泌物的组成和杀菌效果。Deberdt等[50]发现前茬为十字花科或豆科与前茬为菊科相比,种植十字花科或豆科时,青枯菌的土壤存活量和当季番茄发病率均会显著下降。寄主植物也可因青枯菌侵染而启动防御系统,分泌具有青枯菌侵染抑制作用的根系分泌物,进而实现抑菌效果[44]。

3.2 土壤矿质元素的影响植物的营养水平与其防御机制密切相关,这最终会影响土传病菌的存活水平和侵染效率[51]。土壤养分元素(如氮、磷、钾)含量处于较低水平时会通过调控寄主植物的生长而间接影响土壤青枯菌的存活。Yang等[51]发现地表氮、磷和钾养分含量较低时不利于植物健康生长,会减弱寄主植物对病原菌的抵抗能力,导致寄主土体中青枯菌的数量增加。除含量外,养分元素的种类和形态也会影响病原菌的土壤存活。例如,适当增加硅素,可诱导抗性增强,有效降低寄主根表的青枯菌数量[52];通过亚磷酸灌根可有效减少入侵寄主根系青枯菌数量[53];钙、硼、镁、钼等元素可有效抑制寄主存在时土体的青枯菌数量,其中钼、钙的抑制效果最好,抑菌率可分别达35.93%和16.93%[54]。研究表明,矿质元素的抑菌作用主要是通过提高植物防御酶系的活性和抗病能力实现的[55]。例如,在铁多酚催化剂作用下,粉状氧化钙(16% W/W)显著抑制了寄主存在的土体中青枯菌的数量,有效控制了青枯病的发生[55]。Fe3+作为根际微生物争夺的稀缺资源,微生物对它的争夺也会显著改变青枯菌的土壤存活。Gu等[56]研究发现,在植物育苗阶段提前加入能高产且不会被青枯菌“窃取”铁载体的有益微生物,可通过抑制病原菌获取Fe3+来实现降低其土壤存活数量的目的。

3.3 土壤其他理化性状的影响土壤理化性状(如含水量、温度和酸碱性等)也可影响青枯菌的土壤存活。高湿环境下寄主存在时土体中青枯菌的存活量会显著提升,因为土壤含水量高会导致寄主防御病菌的相关基因表达下调,进而使得寄主根表青枯菌的存活量增加[57]。但是,当土壤含水量过高,土壤呈厌氧状况时,青枯菌则可能会因呼吸作用受阻引起土体存活量降低[58]。土壤升温会在一定程度上改善土壤的理化环境(如加快有机质分解、增加营养元素的浓度),但当温度达到一定程度后(如70℃),其对青枯菌土壤存活影响最终表现为抑制[59]。由于土壤温度和水分传导均与土壤容重密切关联,因而土壤的单位体积质量也与青枯菌的土壤存活存在关联。Yamfang等[59]研究发现,土壤单位体积质量越小,青枯菌对土壤热量的响应越强烈。土壤酸碱性对青枯菌的影响比较复杂,既有直接作用也有间接作用。土壤酸性条件下(如pH 4.5~5.5)有利于寄主存在时土体中青枯菌的生长,不利于有益菌(如荧光假单胞菌和蜡样芽孢杆菌等)的生长,促进了青枯菌土体的存活[60]。Wang等[61]也发现土壤pH变化会引起土壤微生物群落变化,而间接地影响青枯菌在土壤中存活。此外,土壤中存在的羟基自由基对青枯菌的抑制效果较好[55]。根据水生生态系统的研究经验,青枯菌的土壤存活状况还可能会受土壤电导率等化学性质影响,但具体作用的方向和程度尚有待进一步试验探究。

值得一提的是,农艺措施(如耕作制度、灌溉和施肥等)也会显著改变青枯菌的土体存活、根际存活和根表存活状况。不过,任何措施的调控本质均是通过改变农田土壤的生物和非生物因素实现的。例如,Niu等[62]研究发现,不同轮作制度(烟-玉米轮作/烟-百合轮作/烟-萝卜轮作)下土壤细菌群落组成和结构差异显著,使得各处理的烟草青枯菌存活状态迥异。灌溉会导致青枯菌的爆发,这或与青枯菌在水分较高的环境下能够以较自由的形式存活有关[63]。生物有机肥主要是因为其中的功能菌多为从健康植株根际分离得到拮抗菌,可通过其拮抗青枯菌作用进而抑制青枯菌在土壤中的存活[64]。

4 结论与展望青枯菌是一种危害性极大的土传病菌,严重威胁世界农业可持续生产和农业经济发展。本文系统总结了影响青枯菌在土壤中存活的主要因素,厘清了青枯菌自身特性、土壤生物和非生物环境对青枯菌土壤存活的作用,对掌握青枯菌的土壤存活动态和集成青枯病防控措施有一定的借鉴意义。同时,本文也提出了今后青枯菌土壤存活影响因素的研究重点及防治注意事项:

(1)探究土壤大中型生物、土壤真菌群落特性以及非专性噬菌体等生物因素对青枯菌土壤存活的影响。蚯蚓、螨虫等大中型土壤动物作为土壤食物网的重要组成,不仅显著影响线虫、原生动物和微生物等青枯菌存活密切相关的因子,而且大型动物的自身活动对土壤结构也有影响,最终影响土壤的水、热、气等。但目前关于蚯蚓、螨虫等大中型土壤动物对青枯菌存活影响的报道尚未出现;同时,土壤真菌群落特性和非青枯菌专性噬菌体等土壤生物因素方面研究也很欠缺。

(2)深入探究土壤酸化、盐渍化等非生物因素对青枯菌土壤存活的影响。土壤生物的分布、存活依赖于特定的土壤环境,相较于生物环境而言,目前对于非生物环境影响青枯菌存活的研究较为薄弱。

(3)加强对全球变化下青枯菌土壤存活状态的探究。全球变化(升温、干旱等)不仅可通过改变土壤水热状况而对青枯菌存活产生直接影响,还可通过改变寄主植物的生长而间接影响土壤中青枯菌的存活。

(4)构建青枯菌土壤的存活预测模型。青枯菌土壤存活的影响因素十分复杂,通过模型设置青枯菌土壤存活各影响因素相关的对象以及参数,将有助于预测特定区域环境条件下各因素对病菌存活的相对贡献,进而得知关键影响因子,为有效防治青枯病提供重要科学依据。

(5)关注多因素互作、重视病原菌的污染源头。理论研究可基于单个因素与青枯菌土壤存活关系进行,而实际防治则需要同时考虑多个因素及其交互作用的影响。同时,考虑到青枯菌的引入主要是由灌溉引起的,因而重视灌溉系统的源头控制有望大幅提高青枯病防治效率。

致谢 衷心感谢朱媛媛、张子赟两位同学在文献查阅过程中予以的帮助!

| [1] |

Hayward A C. Biology and epidemiology of bacterial wilt caused by Pseudomonas solanacearum[J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 1991, 29(1): 65-87. DOI:10.1146/annurev.py.29.090191.000433

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Wang H M, Wu Y C, Shen B. Characterization and biological effects of antigonistic N5 against Ralstonia solanacearum (In Chinese)[J]. Soils, 2013, 45(6): 1082-1090. [王洪梅, 吴云成, 沈标. 青枯病生防菌N5的特性及其生物学效应[J]. 土壤, 2013, 45(6): 1082-1090.]

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Song S, Sun L, Shi J X, et al. Effects of successive application of bioorganic fertilizer on controlling tobacco wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum (In Chinese)[J]. Soils, 2013, 45(3): 451-458. [宋松, 孙莉, 石俊雄, 等. 连续施用生物有机肥对烟草青枯病的防治效果[J]. 土壤, 2013, 45(3): 451-458.]

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Jiang G F, Wei Z, Xu J, et al. Bacterial wilt in China: History, current status, and future perspectives[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2017, 8: 1549. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2017.01549

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Grey B E, Steck T R. The viable but nonculturable state of Ralstonia solanacearum may be involved in long-term survival and plant infection[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 67(9): 3866-3872. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.9.3866-3872.2001

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Lee C G, Iida T, Inoue Y, et al. Prokaryotic communities at different depths between soils with and without tomato bacterial wilt but pathogen-present in a single greenhouse[J]. Microbes and Environments, 2017, 32(2): 118-124. DOI:10.1264/jsme2.ME16136

(  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Ottemann K M, Miller J F. Roles for motility in bacterial-host interactions[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 1997, 24(6): 1109-1117. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4281787.x

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Spraker J E, Sanchez L M, Lowe T M, et al. Ralstonia solanacearum lipopeptide induces chlamydospore development in fungi and facilitates bacterial entry into fungal tissues[J]. The ISME Journal, 2016, 10(9): 2317-2330. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2016.32

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Peyraud R, Cottret L, Marmiesse L, et al. A resource allocation trade-off between virulence and proliferation drives metabolic versatility in the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2016, 12(10): e1005939. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005939

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Wu D S, Ding W, Zhang Y, et al. Oleanolic acid induces the type III secretion system of Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015, 6: 1466.

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Zhang Y, Li J, Zhang W Q, et al. Ferulic acid, but not all hydroxycinnamic acids, is a novel T3SS inducer of Ralstonia solanacearum and promotes its infection process in host plants under hydroponic condition[J]. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2017, 8: 1595. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2017.01595

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Khokhani D, Lowe-Power T M, Tran T M, et al. A single regulator mediates strategic switching between attachment/spread and growth/virulence in the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. mBio, 2017, 8(5): e00895-17.

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Lowe T M, Ailloud F, Allen C. Hydroxycinnamic acid degradation, a broadly conserved trait, protects Ralstonia solanacearum from chemical plant defenses and contributes to root colonization and virulence[J]. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, 2015, 28(3): 286-297. DOI:10.1094/MPMI-09-14-0292-FI

(  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Ahmad S, Lee S Y, Kong H G, et al. Genetic determinants for pyomelanin production and its protective effect against oxidative stress in Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(8): e0160845. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0160845

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Brown D G, Swanson J K, Allen C. Two host-induced Ralstonia solanacearum genes, acrA and dinF, encode multidrug efflux pumps and contribute to bacterial wilt virulence[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 73(9): 2777-2786. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00984-06

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Stevens P, Overbeek L S, van Elsas J D. Ralstonia solanacearum ΔPGI-1 strain KZR-5 is affected in growth, response to cold stress and invasion of tomato[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2011, 61(1): 101-112. DOI:10.1007/s00248-010-9728-0

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Tans-Kersten J, Huang H, Allen C. Ralstonia solanacearum needs motility for invasive virulence on tomato[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2001, 183(12): 3597-3605. DOI:10.1128/JB.183.12.3597-3605.2001

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Yao J, Allen C. Chemotaxis is required for virulence and competitive fitness of the bacterial wilt pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2006, 188(10): 3697-3708. DOI:10.1128/JB.188.10.3697-3708.2006

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Li P, Yin W F, Yan J L, et al. Modulation of inter- kingdom communication by PhcBSR quorum sensing system in Ralstonia solanacearum phylotype I strain GMI1000[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 1172. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01172

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Flemming H C, Wingender J. The biofilm matrix[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2010, 8(9): 623-633. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2415

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Tran T M, MacIntyre A, Hawes M, et al. Escaping underground nets: Extracellular DNases degrade plant extracellular traps and contribute to virulence of the plant pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2016, 12(6): e1005686. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005686

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Yao J, Allen C. The plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum needs aerotaxis for normal biofilm formation and interactions with its tomato host[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2007, 189(17): 6415-6424. DOI:10.1128/JB.00398-07

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Mori Y, Inoue K, Ikeda K, et al. The vascular plant-pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum produces biofilms required for its virulence on the surfaces of tomato cells adjacent to intercellular spaces[J]. Molecular Plant Pathology, 2016, 17(6): 890-902. DOI:10.1111/mpp.12335

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Furusawa A, Uehara T, Ikeda K, et al. Ralstonia solanacearum colonization of tomato roots infected by Meloidogyne incognita[J]. Journal of Phytopathology, 2019, 167(6): 338-343. DOI:10.1111/jph.12804

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Wei Z, Song Y Q, Xiong W, et al. Soil protozoa: Research methods and roles in the biocontrol of soil-borne diseases (In Chinese)[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2021, 58(1): 14-22. [韦中, 宋宇琦, 熊武, 等. 土壤原生动物——研究方法及其在土传病害防控中的作用[J]. 土壤学报, 2021, 58(1): 14-22.]

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Xiong W, Song Y, Yang K M, et al. Rhizosphere protists are key determinants of plant health[J]. Microbiome, 2020, 8(1): 27. DOI:10.1186/s40168-020-00799-9

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Ma C, Gong X, Gao H J, et al. Legacy impacts on the relationships between soil microbial community and the invasion potential of non-indigenous bacteria (In Chinese)[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2018, 38(22): 7933-7941. [马超, 龚鑫, 郜红建, 等. 历史因素对土壤微生物群落与外来细菌入侵间关系的影响[J]. 生态学报, 2018, 38(22): 7933-7941.]

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Jousset A, Scheu S, Bonkowski M. Secondary metabolite production facilitates establishment of rhizobacteria by reducing both protozoan predation and the competitive effects of indigenous bacteria[J]. Functional Ecology, 2008, 22(4): 714-719. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01411.x

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Wu K, Su L, Fang Z, et al. Competitive use of root exudates by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens with Ralstonia solanacearum decreases the pathogenic population density and effectively controls tomato bacterial wilt[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2017, 218: 132-138. DOI:10.1016/j.scienta.2017.01.047

(  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Kwak M J, Kong H G, Choi K, et al. Rhizosphere microbiome structure alters to enable wilt resistance in tomato[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2018, 36(11): 1100-1109. DOI:10.1038/nbt.4232

(  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Raza W, Ling N, Liu D Y, et al. Volatile organic compounds produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens WR-1 restrict the growth and virulence traits of Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. Microbiological Research, 2016, 192: 103-113. DOI:10.1016/j.micres.2016.05.014

(  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Spraker J E, Jewell K, Roze L V, et al. A volatile relationship: Profiling an inter-kingdom dialogue between two plant pathogens, Ralstonia solanacearum and Aspergillus flavus[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 2014, 40(5): 502-513. DOI:10.1007/s10886-014-0432-2

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Wei Z, Yang T J, Friman V P, et al. Trophic network architecture of root-associated bacterial communities determines pathogen invasion and plant health[J]. Nature Communications, 2015, 6: 8413-8422. DOI:10.1038/ncomms9413

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Hu J, Wei Z, Friman V P, et al. Probiotic diversity enhances rhizosphere microbiome function and plant disease suppression[J]. mBio, 2016, 7(6): e01790.

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Li M, Wei Z, Wang J N, et al. Facilitation promotes invasions in plant-associated microbial communities[J]. Ecology Letters, 2019, 22(1): 149-158. DOI:10.1111/ele.13177

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Irikiin Y, Nishiyama M, Otsuka S, et al. Rhizobacterial community-level, sole carbon source utilization pattern affects the delay in the bacterial wilt of tomato grown in rhizobacterial community model system[J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2006, 34(1): 27-32. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2005.12.003

(  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Roy N, Choi K, Khan R, et al. Culturing simpler and bacterial wilt suppressive microbial communities from tomato rhizosphere[J]. The Plant Pathology Journal, 2019, 35(4): 362-371. DOI:10.5423/PPJ.FT.07.2019.0180

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Ye M, Sun M M, Huang D, et al. A review of bacteriophage therapy for pathogenic bacteria inactivation in the soil environment[J]. Environment International, 2019, 129: 488-496. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2019.05.062

(  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Elhalag K, Nasr-Eldin M, Hussien A, et al. Potential use of soilborne lytic Podoviridae phage as a biocontrol agent against Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. Journal of Basic Microbiology, 2018, 58(8): 658-669. DOI:10.1002/jobm.201800039

(  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Murugaiyan S, Bae J Y, Wu J, et al. Characterization of filamentous bacteriophage PE226 infecting Ralstonia solanacearum strains[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2011, 110(1): 296-303. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04882.x

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Perrier A, Peyraud R, Rengel D, et al. Enhanced in planta fitness through adaptive mutations in EfpR, a dual regulator of virulence and metabolic functions in the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2016, 12(12): e1006044. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006044

(  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Wang X F, Wei Z, Yang K M, et al. Phage combination therapies for bacterial wilt disease in tomato[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2019, 37(12): 1513-1520. DOI:10.1038/s41587-019-0328-3

(  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Wang X F, Wei Z, Li M, et al. Parasites and competitors suppress bacterial pathogen synergistically due to evolutionary trade-offs[J]. Evolution, 2017, 71(3): 733-746. DOI:10.1111/evo.13143

(  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Gu Y A, Wei Z, Wang X Q, et al. Pathogen invasion indirectly changes the composition of soil microbiome via shifts in root exudation profile[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2016, 52(7): 997-1005. DOI:10.1007/s00374-016-1136-2

(  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Yang T, Wei Z, Friman V, et al. Resource availability modulates biodiversity-invasion relationships by altering competitive interactions[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2017, 19(8): 2984-2991. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.13708

(  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Yang T, Han G, Yang Q, et al. Resource stoichiometry shapes community invasion resistance via productivity-mediated species identity effects[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2018, 285(1893): 20182035. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2018.2035

(  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Li S L, Xu C, Wang J, et al. Cinnamic, myristic and fumaric acids in tobacco root exudates induce the infection of plants by Ralstonia solanacearum[J]. Plant and Soil, 2017, 412(1/2): 381-395.

(  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Gu Y A, Hou Y G, Huang D P, et al. Application of biochar reduces Ralstonia solanacearum infection via effects on pathogen chemotaxis, swarming motility, and root exudate adsorption[J]. Plant and Soil, 2017, 415(1/2): 269-281.

(  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Tang C S, Wat C K, Towers G H N. Thiophenes and benzofurans in the undisturbed rhizosphere of Tagetes patula L[J]. Plant and Soil, 1987, 98(1): 93-97. DOI:10.1007/BF02381730

(  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Deberdt P, Gozé E, Coranson-Beaudu R, et al. Crotalaria spectabilis and Raphanus sativus as previous crops show promise for the control of bacterial wilt of tomato without reducing bacterial populations[J]. Journal of Phytopathology, 2015, 163(5): 377-385. DOI:10.1111/jph.12333

(  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Yang S D, Jun W U, Zhao J C, et al. Physical, chemical and biological characteristics analysis of rhizosphere soils between infected plants of tomato bacterial wilt and non-infected plants[J]. China Vegetables, 2013, 22: 64-69.

(  0) 0) |

| [52] |

Ghareeb H, Bozsó Z, Ott P G, et al. Transcriptome of silicon-induced resistance against Ralstonia solanacearum in the silicon non-accumulator tomato implicates priming effect[J]. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology, 2011, 75(3): 83-89. DOI:10.1016/j.pmpp.2010.11.004

(  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Norman D J, Chen J, Yuen J M F, et al. Control of bacterial wilt of Geranium with phosphorous acid[J]. Plant Disease, 2006, 90(6): 798-802. DOI:10.1094/PD-90-0798

(  0) 0) |

| [54] |

郑世燕. 矿质营养Mo对烟草抗青枯病的影响及生理生化机理[D]. 重庆: 西南大学, 2014. Zheng S Y. Effect of mineral molybdenum on tobacco bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum[D]. Chongqing: Southwest University, 2014. (  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Morikawa C K. Generation of hydroxyl radicals by Fe-polyphenol-activated CaO2 as a potential treatment for soil-borne diseases[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8(1): 9752. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-28078-6

(  0) 0) |

| [56] |

Gu S H, Wei Z, Shao Z Y, et al. Competition for iron drives phytopathogen control by natural rhizosphere microbiomes[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2020, 5(8): 1002-1010. DOI:10.1038/s41564-020-0719-8

(  0) 0) |

| [57] |

Jiang Y S, Huang M J, Zhang M X, et al. Transcriptome analysis provides novel insights into high-soil- moisture-elevated susceptibility to Ralstonia solanacearum infection in ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe cv. Southwest)[J]. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 2018, 132: 547-556. DOI:10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.10.005

(  0) 0) |

| [58] |

Cai Z C, Zhang J B, Huang X Q, et al. Application of reductive soil disinfestation to suppress soil-borne pathogens (In Chinese)[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2015, 52(3): 469-476. [蔡祖聪, 张金波, 黄新琦, 等. 强还原土壤灭菌防控作物土传病的应用研究[J]. 土壤学报, 2015, 52(3): 469-476.]

(  0) 0) |

| [59] |

Yamfang M, Thepa S, Kongkiattikajorn J. Development of a solar hot water system and investigation of the effects of soil density to inhibit microbial performance in soil with hot water dropping[J]. Renewable Energy, 2018, 117: 28-36. DOI:10.1016/j.renene.2017.10.026

(  0) 0) |

| [60] |

Li S L, Liu Y Q, Wang J, et al. Soil acidification aggravates the occurrence of bacterial wilt in South China[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 703. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00703

(  0) 0) |

| [61] |

Wang R, Zhang H C, Sun L G, et al. Microbial community composition is related to soil biological and chemical properties and bacterial wilt outbreak[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7(1): 343. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-00472-6

(  0) 0) |

| [62] |

Niu J J, Chao J, Xiao Y H, et al. Insight into the effects of different cropping systems on soil bacterial community and tobacco bacterial wilt rate[J]. Journal of Basic Microbiology, 2017, 57(1): 3-11. DOI:10.1002/jobm.201600222

(  0) 0) |

| [63] |

[Álvarez B, López M M, Biosca E G. Survival strategies and pathogenicity of Ralstonia solanacearum phylotype II subjected to prolonged starvation in environmental water microcosms[J]. Microbiology, 2008, 154(11): 3590-3598.]

(  0) 0) |

| [64] |

Wei Z, Yang X M, Yin S X, et al. Efficacy of Bacillus-fortified organic fertiliser in controlling bacterial wilt of tomato in the field[J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2011, 48(2): 152-159. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2011.03.013

(  0) 0) |

2021, Vol. 58

2021, Vol. 58